EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the fifth in an ongoing series of features highlighting authors and new books published by Torrey House Press in Utah.

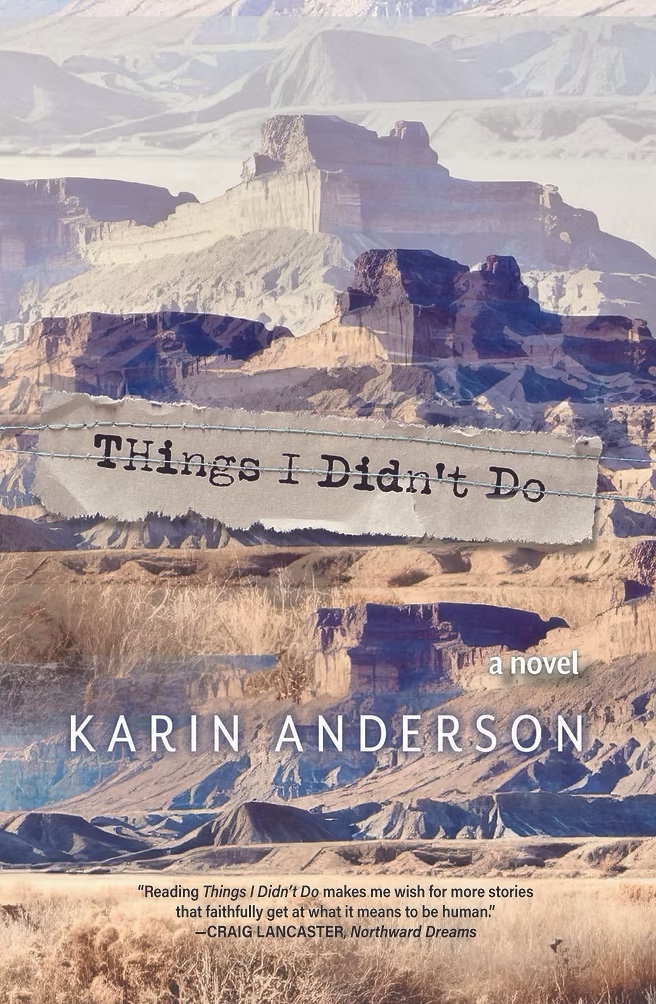

There is only one fiction book being published this year by Torrey House Press, but it is an impressive newcomer to the pantheon of outstanding Utah narratives. Karin Anderson’s Things I Didn’t Do, a bona fide saga set in the Book Cliffs of eastern Utah, revolves around Ryder Mikkelson, taking readers from an accident that messed up his leg at the age of seven to thirty-four years later when his twin daughters return from college with news that leads him to finally acknowledge and accept the roots of his identity and the memories of his upbringing.

Anderson’s storytelling reverberates in a counterpoint of plain-spoken truths and sweeping lyricism that puts us in an area that clings to the past. It was once home for miners, trappers and outlaws. There is an abundance of wildlife matched in scale and scope by the emotional, domestic and economic hardships that hit hard in the region’s tiny ranching communities. Anderson’s novel spans four decades, starting in the 1980s and ending shortly after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s. In the Book Cliffs region in eastern Utah, Mormonism remains an anchor that simultaneously influences and confounds every individual’s pursuit of becoming the perfect family man or matriarch.

Along with their respective families, Ryder, Kent and Ferron live in remnants of the Old West, far enough away from the Mormon hubs of power in Salt Lake City or the central Utah Valley regions to be neglected if not almost wholly ignored. The boys witness disappointment, guilt, depression, addictions and family crises associated with the culture of unattainable perfectionism. The stigma of such shortcomings chastens and diminishes men who were brought up to be confident and strong providers. Meanwhile, women are vulnerable to become embittered and disillusioned by a culture that prioritizes traditional roles of mother and wife without the benefit of a leading voice either in their families or communities.

In the novel, Evaleen Mikkelson, Ryder’s mother, transcends the barriers, toxicities and the limitations of that culture and accomplishes this in a manner that will surprise many readers who cling to specific stereotypes. Evaleen’s faith is simultaneously unconditional and realistic. She is a paragon of virtue, her wisdom ensconced in her genuine practice of not judging irrationally while accepting with resourceful resolve the unflinching realities of life. Coming from a broken home, Evaleen learned to hunt with rifle skills that impress her husband, Alma. Early in the story, it is 1986 and Ryder asks his father why his mother Evaleen won’t hunt, even though she is known for her skills with a hunting rifle. “Look, Ryder. Your mother’s been through a lot. She had it rough as a girl and rough in other ways as a woman,” Alma, the father, says. “But she picked up skills. Like rifle aim. She grew up in a big desert. She knows them west mountain ranges as well as any man.”

When Ryder learns about his mother’s broken family and that her father was a philanderer, he presses his dad to explain. Alma says, “Wrong kind of dreamer. Worked hard on the railroad when he was young, then I guess wanted a way out. Thought he could find one last silver lode. And he was a hard drinker. Her mama had kid after kid. When I married Evaleen, she could out-tough me in just about every category, and I was raised plenty hard.”

Unable to bear children, Evaleen and Alma adopted Ryder — a fact that the boy is shocked to learn when he is hospitalized for one of the many surgeries he will need to mend his broken leg. The story’s central emotional tension for Evaleen and Ryder encompasses questions about his adoption that permeate the story’s span stretching across more than three decades.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Anderson, a former professor of English at Utah Valley University whose other published stories have captivated Torrey House Press followers, talked about how growing up in a small Great Basin town set the path for her. “I thought I was going to be an art major but that didn’t match up with what I was hungering for,” she said.

In a general education literature course, she encountered The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer in Middle English, which she described as an “incredibly powerful” experience. “The stories were so down to earth and I was amazed that they could bring to mind the life, environment and milieu so vividly hundreds of years later,” she explained, adding that it inspired her to write about her own people and her own time.

Other writers that inspired Anderson to cultivate her literary voice included muses who reflected their own geographic homes, including Flannery O’Connor, known for her Southern Gothic style and Ivan Doig, who has written fiction and nonfiction about his native Montana. Another is Kathleen Dorothy Blackburn, whose memoir Loose of Earth includes stories about growing up in Lubbock, Texas in a family of evangelical Christians who opted for homeschooling for their children and believed that science was based on literal Biblical interpretation. And, there is the late Carol Shields, whose final novel, Unless (2002) resonates with the likes of Anderson’s characters in Things I Don’t Do. In an interview published in Random Illuminations, Shields said, “I like to think of this book on these four little legs: this idea of mothers and children; the idea of writers and readers – I wanted to talk about the writing process; I wanted to talk about goodness; and then I wanted to talk about men and women – this gender issue, which interests me so much and has actually been a part of every book I’ve written. I think I am always writing about this.”

Anderson said this was the easiest novel she has written. Astute readers will assemble this elegant puzzle, as we follow Ryder’s epiphanic journey to comprehend and to accept the story of his own birth and eventual adoption by Alma and Evaleen. As a boy, Ryder learns that he was adopted when he was in the hospital for surgeries after he fell from a loaded pack mule high in the Book Cliffs. Ryder is upset that Ferron and Kent knew and wonders why Evaleen didn’t tell him. “I couldn’t stand to tell you anything that would make you question that,” she says. “Not until you were old enough to understand. And I didn’t want your friends to treat you different from other kids.”

For those who read What Falls Away, her 2023 release, the connection to Things I Didn’t Do will become apparent. And, for those who read Things I Didn’t Do, the experience will be enriched by following up with a reading of What Falls Away. The characters as well as Ryder’s story about his adoption and the dynamics of estrangement came from her observations about growing up in central Utah and the Utah Valley where women her age were sent away for becoming pregnant or whose memories were haunted when the newborn was taken away and put up for adoption. The boys and their fathers portrayed in Things I Didn’t Do, likewise, echo in part the experiences of Anderson’s nephews as well as the male students she would have when she taught at Utah Valley University. “I’m a mother of sons (daughters too),” Anderson said. “I see how difficult it can be for boys in our culture to define for themselves what positive manhood means. I also see how many find their way. I wanted to write a novel about boys and, by implication, about their essential relationships with maternal figures, and with women as partners, friends, teachers, and daughters.”

Ryder, who develops his artistic talents for drawing, epitomizes a good man who answers earnestly to who he is. Anderson gives Ryder in his boyhood the tools to cultivate his identity with his humble roots in tiny Etna, a town where “nobody knew where it was unless they knew all the other places, too.” Utterly bored, stuck in bed and unable to walk, Ryder is drawn to the story of Anno, a Japanese boy who wonders what is beyond the sea.

Anderson paints a stunning word portrait of the Book Cliffs, Mormons, the San Rafael River, the home of the Paiutes and Utes, the coal miners, the power plant smokestack, the highland ranchers, sheepherders and cowboys. Realizing that drawing is a universal language in its own merit, Ryder “wanted someone like Anno to see how strange, how regular, how beautiful were the nooks and heights and cliffs and river hideouts of his own home.”

In the novel, the men’s stories are riddled with disempowering effects of disconnection, confusion, helplessness and economic disenfranchisement. However, with Ryder and Kent, Anderson illuminates the emotional faith that men can still act upon to think about themselves, their capacity for love and family and their life potential. With moments of flashbacks and flash forwarding, Anderson commands the reader to see for themselves what transpires for Ryder, Kent and Ferron — the trio of boys at the heart of this exceptional quintessentially Utah saga.

Alma reminds the young Ryder that women “got their own sorrows,” adding that “boys are raised to pick a direction and keep going. Women though, circumstance turns them every which way.” When Ryder asks his dad to specify, Alma tells him that he will discover it on his own, especially if he pays attention and is kind to those around him. No question that Alma has made plenty of mistakes and nearly succumbed to his own vulnerabilities.

Ryder takes his father’s words to heart, evidenced by the essay that he writes for his sophomore level English class. He mentions that he finds it easier to talk to his dad than his mother about where he came from and then he continues:

My dad and me had a hard time for a few years while he was going through some things, but we can talk about most things better now. I think he knows I love him and I will always call him my Dad. But it’s harder for my Mom maybe because she’s had a pretty hard life and she always wanted to be a Mom and to love her own child or children so when I came to be her Son she must have thought she had to hold on tight. It’s weird because she’s taught me lots of important things. She’s the one who talks to me about the hard things in life and she’s not scared of anything but then again she can’t talk about this subject without kind of falling apart so I just avoid it with her. Mostly because I don’t want to hurt her feelings but also because it’s not worth the hassle. So right now I don’t think I’ll look for any answers because why should I ever hurt my mom, Evaleen Mikkelson.

The essay Anderson pens in Ryder’s voice is an ingenious device because it shows his gradual progress as a decent human being. It emphasizes how Anderson sees the novel as a love letter to the male students who were enrolled in her writing courses. “Grading is a horrid way to respond to any student’s effort and risk; it interfered with my ability to express how profoundly I was affected by their experiences and ruminations,” she explained. “It interfered with their trust in the humanity of language. But they rose to it, again and again. In a culture that proscribes masculine expression, I valued my rare access to the astute perceptions of men who might otherwise seem ‘unreadable.’”

In his essay, Ryder writes that he understands that his grade might be lower because he did not reach the word count indicated for the assignment. “Although the fictional essay is written by a fictional boy, I found myself beseeching the fictional English teacher to read beyond his errors,” Anderson added, “to soften the rigid requirements of the assignment to give Ryder the articulate, encouraging response he deserved.” The impact of that essay is manifested 25 years later when his twin college-age daughters bring home surprising news that ends up resolving the quest referenced in the last sentence of that 10th grade essay.

Kent and Ferron also must contend with the character frailties of their parents, Doug and Maura. Doug is swept up in talk radio’s obsession with conspiratorial fantasies and Maura who abandons the family cannot abide how Mormons hogtie individuals. Maura tells Alma that he should not feel guilty about drinking or the fact that Evaleen could not see a pregnancy to its full term: “Evaleen can believe what she wants about cause and effect. I respect her more than all the present company combined. But God’s got better things to worry about than Evaleen’s — ovaries. All she went through has nothing to do with some piss-poor Mormon God getting worked up over who drinks a beer. Or who got bumped up and who collected. Catholic God tallies up and calls it good.”

Meanwhile, Ryder’s family face numerous economic woes, compounded by years of medical bills. The lessons deepen for Ryder when he stays with the eccentric curmudgeon that is his great-grandfather whose home looks like a junkyard, but who also is one of Evaleen’s most passionate defenders. Alma is working out at Dugway, nearly 200 miles away, to earn enough to chip away at Ryder’s medical bills.

These days are not easy for Alma, Evaleen or Ryder. Alma vets his frustration and fury in a moment that jolts Ryder into thinking the darkness is inescapable. Alma is infuriated that Evaleen was speaking in a way that practically broadcasts to the entire valley that he is a poor family provider. “Now we got doctor bills we’ll never pay down. We sold our land in Etna. I sleep out to that godforsaken Depot, burn poison all day long, and when I come home it ain’t home,” Alma says. “I live in a shack in a junkyard in a ghost town with an ingrate and a coot just so I can be with the woman I love. We can’t keep food on the table longer than the half minute it takes for you and that half-wit kid can’t stop coming around to inhale it.”

Never has Ryder heard his father speak with such darkness but he also is angry at his mother for not sharing details about another kid’s life, especially when apparently everyone else in town seems to know his story. Throwing such a tantrum that he even refuses to eat one of his favorite dishes that his mother just made, Ryder is feeling exasperated. But Evaleen’s maternal instincts always kick in at the proper moments. She opens up to Ryder shortly thereafter, sharing stories not only about the young lad in question and his difficult family life but also about her own father. Ryder realizes the tension Evaleen feels is because Alma has to work so far away. She tells Ryder, “I’m not pretending things ain’t hard for us right now. They are. It’s not your fault. You didn’t make bad things happen. Neither did your dad. Or me. Life is a rough ride. Sometimes we take a tumble. But we’re okay. We’ll figure it out.”

There are many strong bonding moments between Ryder and Evaleen: for example, when she teaches him how to drive or when she discusses the aftermath of a nasty scuffle at school that affected Russell, the boy Ryder and his mother argued about previously. Evaleen knows that both Ryder and Russell are vulnerable to the idea of loss or feeling entirely out of place. “Young men can get on the wrong path. Maybe they see too much too soon,” she says. “They’re strong, full of juice, too much power but not much at all. Some learn to wield what force they can. Do you understand what I’m talking about?” Russell, Evaleen says, has a chance to be a better man than he could have had in his brother or father.

With Ryder’s hero journey, Anderson makes handy use of bears as a Jungian archetype. Art also serves a practical function for Ryder, much as the petroglyphs in the Book Cliffs served for the Indigenous communities of many years ago. But, art’s practicality also extends to the emotions of grief, which Ryder expresses when he paints the panels on Ferron’s truck after taking over the business, following his death. Meanwhile, Kent takes the scientific parallel to Ryder’s artistic route, eventually earning his doctorate in geology. The novel’s exploration of place and identity makes for a gripping read.

Ryder’s strong relationship with Sami, his wife who has Diné origins, is possible, thanks to his years of growing up with Evaleen. Kent and Ferron are not as fortunate, as Maura abandons Doug, their father. Ryder comprehends the crucial impact of having a rock solid mother when he sees other boys in school and the community struggling because of drugs, abuse and broken homes. Late in the novel, Anderson summarizes the mature evolution of Ryder and Kent: “Grown Kent is a shapeshifter in Ryder’s eyes: small rat-tail Kenty bangs inside the walls of smirking libtard Professor Mikkelson. Small Ryder inside the tall husband and father doesn’t know what to make of a self-respecting straight guy from Emery County with a rainbow sticker on the back window of his pickup. Just below the gun rack.”

As adults, Ryder and Kent fully understand the differences between their fathers. Ryder, now the father of two daughters and content in his family life with Sami, says, “My dad did right by me. Even when I was a pain in the ass. Our dads weren’t raised to have kids. Scares the shit outta me, thinking how unready they were to be husbands. Fathers. Because—damn. I was too.” Kent adds that Ryder’s dad was “just a nice ignorant country guy…[who] learned as he went,” while his “never learned shit.” Ryder says that surely cannot be the case or otherwise Ferron, who was philosophical and gay, would not have been possible. Kent tells Ryder, “Mom made Ferron…Whatever that was, it’s not going any further. Like I said a long time ago, you’re lucky there’s none of it in you.”

A masterpiece of Utah literature, Anderson’s novel is a literary gem that exemplifies the outstanding vanguard of Torrey House Press authors whose fiction and nonfiction have illuminated the most commendable path of enlightenment in American West storytelling.