A first-generation American, Denny is hustling to grab the brass ring on the carousel of the American Dream. In 2007, lonely and dissatisfied with the dead end of lower income working life, he steals and resells bicycles and occasionally breaks into cars. While Denny is a petty thief, he also is a loving and faithful son to his Japanese mother, especially when they spend time together reading letters from their relatives in Asia. Whatever joys they have in their lives are modest but still heart warming, even when they are spending time at a park. His mother’s biggest concern is Denny pays the electric bill on time.

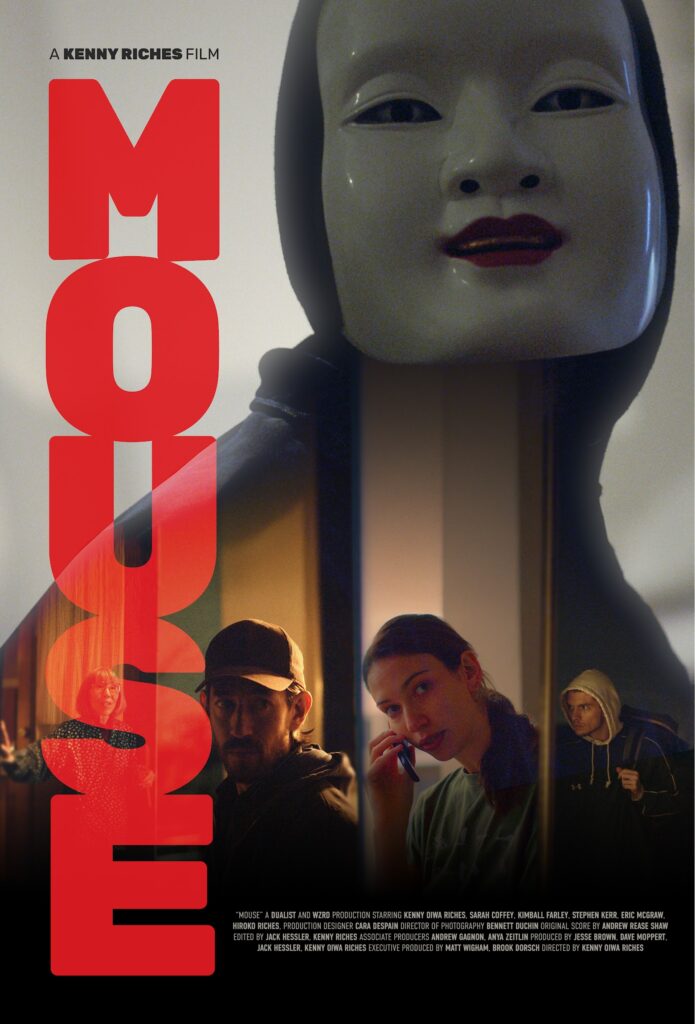

This is the starting premise of Mouse, an award-winning independent film produced and shot in Salt Lake City, which is about to expand its festival circuit screening tour. Directed by Kenny Riches, who also stars as Denny, this understated yet richly textured narrative also features his real-life mother, Hiroko Riches, as Nobuko, Denny’s mother. Mouse, Riches’ fourth feature-length film, took two top honors at this year’s Brooklyn Film Festival, winning Best Narrative Feature and the prestigious Grand Chameleon Award.

To ease his loneliness, Denny responds to a classified ad for pen pals and begins corresponding with Tess (Sarah Coffey) and he contrives a false persona as a successful and wealthy businessman which gradually enchants Tess. However, Denny is unaware that Tess and Maury, her actual boyfriend, Maury (Kimball Farlay), are running a scam that exploits lonely clients. When Tess and Maury run into financial troubles that puts them at risk for physical harm, they decide to travel to Salt Lake City, believing they can milk Denny for his wealth. Of course, when Tess and Denny finally meet, everything unravels.

Denny is aware of the moral tensions involved. In the first half of the film, he makes it evident that he does not intend to expand or extend the realm of his current petty thief activities. He is always mindful of his mother and would never dare abandon her or put her at risk of ending up being more lonely and isolated than she already is. However, when Tess makes up the story that she is coming to Salt Lake City for a job interview and would love to meet him, Denny realizes that he is crossing the line into uncertain territory that carries potentially far more serious consequences. Hence, the story picks up on the tensions of how Denny wrestles with just how much further he should continue with this pretense, especially when it becomes apparent that Tess is also not the person she claimed to be in her letters.

In his director’s statement, Riches notes the intersecting and confounding effects of bias and class dynamics. He writes, “I wanted to make a film about a new American; a first-generation American, like myself, who inherited aspects from two different cultures, one of which is Asian, a/k/a the ‘model minority.’” Thanks to Riches’ strategically astute narrative choices, which resonate and are amplified by the fact that both he and his real-life mother play their respective roles in their film, the story rides easily along the undercurrents of the ‘model minority’ myth.

Nearly 60 years ago, sociologist William Peterson helped popularize the term in an article carrying the headline, Success Story, Japanese-American Style, for the New York Times Magazine. Peterson situated the story in the context of American history of immigration, specifically the Japanese. He originally intended the term ‘model minority’ to apply specifically to the Japanese but the term eventually encompassed immigrants from many other Asian countries. In citing the Japanese, Peterson explained that “diligence in work, combined with simple frugality, had an almost religious imperative, similar to what has been called ‘the Protestant ethic’ in Western culture.” Eventually that description would spread to other Asian groups, most notably Koreans and Chinese.

As Baodong Liu, a University of Utah Presidential Societal Impact Scholar, explained, “Model minority, as it was first coined, seemingly described Asian Americans’ accomplishments. The term was intended as an accolade. As it became more popular in the public sphere, however, the term generated emotional, sometimes antagonistic, reactions from the Asian American communities. Many Asian-American scholars held a negative view about the implications of the term.”

Likewise, Frank Wu, author of Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White, cited three reasons why the term must be rejected: “a gross simplification that is not accurate enough to be seriously used for understanding 10 million people… it conceals within it an invidious statement about African Americans along the lines of the inflammatory taunt: ‘They made it; why can’t you?’… the myth is used both to deny that Asian Americans experience racial discrimination and to turn Asian Americans into a racial threat.”

While these forces are not explicated in Mouse’s narrative, one can sense that they are simmering underneath, especially as they subtly propel the story arc and emotional evolution for all four central characters. Riches, in his director’s statement, described it as “a strangely personal film, with admittedly Denny’s hustles being inspired by my own youth and, of course casting my real-life mother to play Denny’s mom.” Indeed, as the film takes place in 2007, years before anyone could have credibly imagined the intensely polarizing American sociopolitical climate of today, the sensations of loneliness, claustrophobia and shattered dreams experienced in Mouse seem even harsher and more dire today.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Riches, who saw his second feature The Strongest Man premiere at Sundance in 2015, said Mouse had its genesis during the pandemic. A starting point came after chatting by phone with a filmmaker friend living in Rhode Island whom he has never met in person and who does not have an online presence. “It made me think about how you could communicate this way and feel a close presence to someone and you might never know that they could be catfishing,” he said.

The characters in Mouse are on the fringes in society for various reasons and are feeling insecure, anxious or do not have a grounded sense of self-esteem. Riches, who was born in Toyota City, Japan, said that growing up in Salt Lake City, he chased trouble and represented a microcosm of what we witness in Denny’s character. Riches added that he eventually told his mother about what he did as a kid.

In 2011, Riches earned his bachelor of fine arts degree in drawing and painting from the University of Utah. Film became his avenue for creative expression and the thematic arc of characters in his films are consistent with Mouse. After its Sundance premiere in 2015, The Strongest Man, a comedy set mainly in Miami about an insecure Cuban man who fancies himself as the strongest man in the world, was picked up by AMC International and Kino Lorber for distribution. He followed up with A Name Without A Place, a narrative about an isolated man trying to trace his late brother’s footprints in the Florida Keys who stumbles upon the secret estate of a narcissistic recluse. It premiered at the Miami International Film Festival and is available on Apple+.

Great mobster films, such as The Godfather and Goodfellas inspired Riches as well. “I loved watching these characters descend deeper into this life and business,” he explained, adding that Mouse is a micro version of this perspective.

Riches also is a partner in Dualist, a production company. Dave Moppert, one of the producers of Mouse, first collaborated with Riches on the 2012 indie film Must Come Down, with Riches directing and Moppert as assistant director. That film, described as a “hysterical commiseration,” follows Ashley and Holly, both twenty-somethings, who are still in arrested development but are trying to navigate their quartet-life crises. The late actor David Fetzer, who was among the most impressive in his career, played one of the leads. Later, Riches was one of the co-founders of The Davey Foundation, a grant-giving organization for filmmakers founded in memory of Fetzer. Also, Andrew Rease Shaw, an Utah-based musician and artist who serves on the foundation’s board of directors, composed the score for Mouse.

Moppert said that since then, it would be hard not to love what Riches does because they share the same interests and tastes in making indie films. The casting offered an extra dose of serendipity besides having Riches and his mother play their actual roles in the screenplay. Farlay and Coffey are also a real-life couple, a factor that heightens the onscreen chemistry between their characters of Maury and Tess.

In Brooklyn, where the film had its festival premiere, Moppert said that his ears were burning as he listened to the audience react with the right emotions at the right times in the story. Riches added that he was a little surprised that the film took two high-profile honors, but we also “heard a lot of high praise and there were interesting questions in the talkback.” As for his mother, Riches said she normally doesn’t like any attention so she skipped the premiere.

Mouse will be screened in Salt Lake at the inaugural Opening Weekend Film Festival, which will take place Oct.10-12 at the Fisher Brewing Company, before heading in November to Film Fest Knox in Knoxville, Tennessee.