Near Salt Lake City, the Bingham Canyon Open Pit Copper Mine sits atop a 70-square-mile underground plume of contaminated groundwater. A burst spilling into the valleys could trigger Utah’s worst environmental disaster ever. While the Gold King Mine spill that occurred in southwestern Colorado attracted a great deal of public attention in early August 2015, similar disasters around the world went virtually unnoticed by the media. A burst in Brazil was even on a larger scale than the Gold King Mine disaster. A breach in British Columbia sent millions upon millions of cubic meters of waste water into the Fraser River, known for its salmon. Likewise, in Mexico, a significant breach went unnoticed.

Complacency and ignorance carry potentially deadly risks, particularly when they are amplified by greed-driven motivations that pit political self-preservation against the presence of scientific evidence and the historical facts of cultural practices and evolution. Jonathon Thompson weaves his skills of investigative journalism and factual verification with the empowering tools and devices of a novelist to bring the reader directly into his new book, River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind The Gold King Mine Disaster. The book is published by Torrey House Press, a Utah-based nonprofit literary enterprise that focuses on stories about environmental conservation and preservation through new lenses of appreciation for the authentic history and culture of the American West.

The result is a 300-page book that digs deep into the history of the Four Corners Country and the impacts that led to the 2015 disaster. Thompson brings a style and impact that reminds readers of other books that brought fresh public awareness to an issue or problem: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone (1994), John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness and Greed (2005) and Michael Lewis’ Flash Boys (2014).

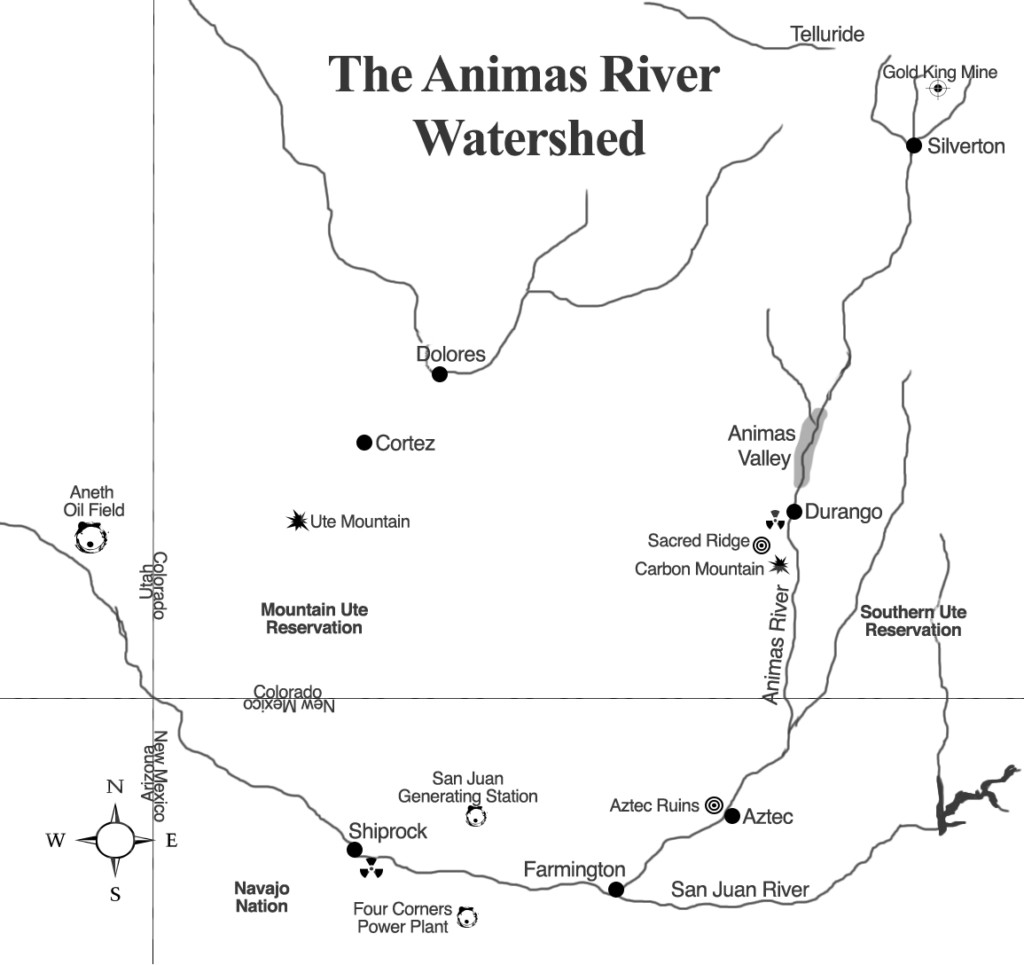

A journalist for more than 20 years whose family roots go back five generations in the Animas Valley that sits at the heart of River of Lost Souls, Thompson was urged to write the book after his coverage of the Gold King Mine disaster at High Country News attracted national attention.

For those living outside the Four Corners Country, their familiarity with the disaster often came through reports following the incident, which implicated negligence on the part of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Republican members of the U.S. Congress pushed for, as Thompson describes it, “Benghazi-like hearings.” In 2016, several U.S. senators attempted to initiate a criminal probe of the EPA’s handling of the problem. Russell Begaye, president of the Navajo Nation, testified at a field hearing that the EPA did not notify the Navajo Nation for two days after the burst occurred, despite the fact that the affected river ran through the Nation’s land. Late in the book, Thompson indicates that the EPA likely missed a critical red flag about where the water was being blocked from in the tunnel.

A Superfund site designation was made in 2016 but once the new presidential administration took office in 2017, efforts to compensate those affected or continue environmental recovery procedures have been delayed indefinitely. Indeed, a rapidly expanding litany of concerns other than environmental disasters seems more important on the minds of many in Washington, D.C., to the frustrations and detriment of the residents and communities most affected by the Gold King Mine events.

However, Thompson rises superbly in overcoming the devils of short attention span and complacency by contextualizing the scientific evidence and historical background in accessible and clear language, often in the words of stakeholders from many stripes in the community spectrum. One of the most pervasive themes in the book is the steady, thoroughly researched dismantling of the mythologized Manifest Destiny historical chronicle. And, readers might be surprised to learn that environmental concerns were raised frequently in the local newspapers during the 19th century, even as mining towns developed at a furious pace.

When Thompson writes about acid mine drainage – “mining’s most insidious, pervasive, and persistent environmental hazard” – he demonstrates comprehensively that this claim is not merely the capricious assertion of a contemporary activist. He mentions De re metallica, a 1556 work by the German-born George Bauer, published under pen name of Georgius Agricola, who wrote, “The fields are devastated by mining operations, for which reason formerly Italians were warned by law that no one should dig the earth for metals and so injure their fertile fields, their vineyards, and their olive groves.” He pulls an excerpt from 1882 which appeared in the Colorado Transcript newspaper, as farmers in Jefferson County voiced their concern about Clear Creek water pollution.

Sediment … chokes the soil wherever it settles, suffocating vegetation and preventing all growth of any plants, while the pyrites and other minerals contained their when spread out and exposed to the action of the air, decompose, chemical action occurs in connection with the alkali and salts of the earth, and the copper, arsenic, and other deadly and poisonous elements are set free, rendered soluble, and thus with every rain and use of water spreads the destruction over a wider domain of the lands.

To help readers visualize the potential consequences of contaminated water with a pH level of below 4.8., he compares it to battery acid. He quotes a 1901 U.S. Geological Survey: “The descent of the meteoric water through masses of pyrite and other ore minerals is often sufficient to give it a strong acid reaction and render it highly ferruginous.” The same report notes that near the Gold King Mine, the Yankee Girl Mine water was so acidic that “candlesticks, picks or other iron or steel tools left in this water became quickly coated with coppers (sulfate salts). Iron pipes and rails were rapidly destroyed, and the constant replacement of the piping and pumps necessary to handle the abundant water was a large item in the working expenses.”

A 1911 flood, which ripped through every drainage in the San Juan mountains, affected areas including the region now encompassing Lake Powell. The concerns were incontrovertible but even the magnitude of the 1911 event did not dissuade the community from the priorities it saw as existential to its viability. As Thompson writes, “Never mind that a horrific flood had caused millions of dollars of damage downstream, that the train couldn’t get to Durango, let alone Silverton, and that reconstruction would take months. We’re a mining town, the headlines screamed, and nothing’s going to get in our way.”

Near the beginning of the book, he situates the historical context of the title, by citing a 1907 article that appeared in the Durango Earner: “soon it will merit the name of Rio de las Animas Perdidas, given it by the Spaniards. With water filled with slime and poison, carrying qualities which destroy all agricultural values of ranchers irrigated therefrom, it will be truly a river of lost souls.”

Yet, as much as he emphasizes the roughly 150 years of mining history of the San Juan Basin that led up to the pivotal Gold King Mine disaster in 2015, Thompson goes back much further – 800 A.D. – to drive home the sense of Place in the Four Corners Country. The region is believed to have been inhabited as early as 10,000 B.C. and the ancestors of the Pueblo people likely arrived as early as 500 B.C. For that history, he turns to Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, the Hopi Tribe’s cultural preservation officer who has been recovering ritual objects and investigating a case of theft that points to Paris.

Twelve centuries ago, as Europe entered its Dark Ages, here the Hopi were dryland farmers, as “acres and acres of corn and beans and squash grew without any liquid nourishment aside from rainfall; the same is true of Hopi today.” Thompson emphasizes that the Hopi had refined their technical instincts and knowledge based on their observations. “They appear to have chosen to put themselves at the mercy of the rains rather than try to wrest control over temperamental waters that rushed down from the mountains,” he explains. “When that failed, they adapted accordingly, sometimes even moving, giving the land a chance to rest. The place shapes them, not the other way around.” Kuwanwisiwma puts the finishing point on the lesson: “We’re a corn culture … The environment can force you to be humble.”

Some 900 years later, as Spanish explorers arrived — Juan Antonio Maria de Rivera, being Thompson’s specific example — it was apparent that the explorers were oblivious to the millennia of history that already had occurred on the lands. “He didn’t know the Diné name for the Animas River, Kinteeldee Ńlíní or ‘Which Flows from the Wide Ruin,” Thompson explains. “And he must not have cared about the Ute name, or any of the many names before. Maybe on some intuitive level, though, he felt that presence in the water, the trees, the mountains, and that is why he said the river was full of souls.”

As Thompson brings the chronology ever closer to the present day, he documents the volatile cycles of profit and economic bust that have marked a century and a half of mining operations. The reader realizes that the frontier history of the American West he or she has previously encountered is utterly useless, suitable only for the commodified entertainment spectacles it has inspired. “Contrary to how today’s peddlers of the wild, wild west, with their fake gunfights, might portray the history of Silverton and Durango, the reality is, this sort of lawless, highway-robbing, gun-slinging, and frontier justice were a mere blip on the region’s record,” he notes.

The most consequential history for the region had been rendered invisible for many decades. The Gold King Mine went bankrupt in the years preceding the Great Depression, after it had yielded more than 700,000 tons of gold, silver lead and copper ore from the San Juan Mountains, with a value of $120 million in today’s currency. As preparations were made to shut the mine, “the tunnel ‘deep drained’ the groundwater running through Bonita Peak, thus leaving the once watery Gold King Level #7 adit almost totally dry,” Thompson explains. “The tainted water that had been pouring out of the mine had been rerouted through the mountain, and now poured from the American Tunnel, instead. Gold King ore would never flow through the American Tunnel, but its acid mine drainage would.”

It is astounding to contemplate the sin of omission committed by so many in chronicling the history of the old West. The truth is that environmental activism always has been at the heart of the story of the American West. Newspaper accounts from the 19th Century, as already noted, confirm this.

After World War I ended, farmers in Clear Creek and municipal representatives from Golden, Colorado, urged state legislators to force mining companies to build settling systems for tailings for mitigating pollution problems affecting those living or farming downstream. Eventually sports fishermen and outdoor recreation enthusiasts joined the efforts, including the nascent Izaak Walton League. They finally won the battle in 1935, when the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in favor of the farmers 4-3 that tailings no longer could be dumped into running streams. The irony is that the riverbed still contains remnants of those tailings which had been dumped between 1870 and 1936.

Thompson sketches many pragmatic but frustrating scenarios. Activists learn to appropriate the experiences of the long game in enduring the frustrations of making awareness campaigns stick and winning protracted court battles. In the middle of the book, he illustrates the scale of what is involved, when he describes the “scare map” in New Mexico, which uses black and red dots to indicate where every gas and oil well drilled in the San Juan Basin is located. There are large swatches of solid color and the perimeters surrounding Chaco Culture National Historical Park and the Huerfano Mountain Dzil Na’oodilii. Chaco is essential to the legacy of the Pueblo and Navajo peoples – the “apogee of civilization in what is now the United States,” as noted in a recent Sierra Club online piece. Navajo activists finally won their campaign to halt drilling near Chaco.

But, the risks of contaminated water are frighteningly ubiquitous. The San Juan Basin, for example, is home to a network of thousands of coalbed methane wells, making the region the world’s largest producer of coalbed methane. To illustrate just how much waste water is generated annually – either put into lined evaporation pounds or injected deep into disposal wells – Thompson cites that for just one geologic formation enough water is generated to fill 3,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

When readers finally get to the final pages of the book, they learn that had a water consent decree been adhered to, there would have been a different outcome than the disastrous spill which occurred in 2015. It becomes evident that of all the remediation efforts, “they don’t hold a candle to active water treatment when it comes to improving water quality,” Thompson explains.

He also cites the insights gleaned from Diné farmers who refused to use the water the EPA provided after the disaster. They stopped irrigating their crops and let their fields go fallow, which initially baffled Thompson because the slug from the disaster was not “especially dangerous,” and “wasn’t even distinguishable from the usual San Juan River silt by the time it reached Utah.”

The takeaway, he concludes, is not found necessarily in science but in the historical value and meaning of Place, which he discusses throughout the book. “Mining had changed the Place,” he writes. “When the dynamite and the draglines chomp apart ancestral grazing lands, it takes away more than just grass, rocks, and shrubs, it also shatters a delicate harmony that had existed between humans and the land for ages. … [and when] the Place gets tainted, as do all who remain there. The trauma gets into our psyches and then into our cells, maybe even our genes, affecting us both psychologically and physiologically.”

In the 1960s, Carson’s book, a masterpiece of literary nonfiction, achieved a good deal. It paved the path to the EPA being established. Likewise, Thompson’s book is vivid, courageous and strategically informative. Despite the current frustrations about a compromised EPA, Thompson reminds us that remediation and reclamation efforts (especially in water treatment) can be revived and expanded, giving us the chance to do the most responsible rehabilitative work in a changed Place.