The layout of the space in the Gittins Gallery at the University of the Utah is perfect for Jorge Rojas’ Coyotek exhibition which mows down the physical and cognitive borders we conventionally imagine. Despite efforts to the contrary to dampen or counter the kinetics of the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico, the fact is that the mythology of the coyote is not exclusively a border phenomenon, but one that has permeated so obsessively that it has been inextricably embedded into the respective American and Mexican consciousness. It is now so fixed that its potential socioeconomic and political impacts will always transcend any efforts to stifle it.

Rojas coined the unique portmanteau of Coyotek to combine icoyote and technology, as it reflects the matters of borders, immigration policy, new media and digital communication. The exhibition synthesizes a body of work he has developed over the last two decades, represented in photography, performance videos, and a newly commissioned site-specific corn mandala, along with installations created over the period and several new works shown for the first time. Coyotek is the second iteration of the traveling exhibition. The first was organized and presented earlier this year at the El Paso Museum of Art in Texas. The show was organized in partnership with ProArtes México.

Rojas was born in Mexico and at the age of six, his mother brought him to the U.S. along with his siblings, but they also moved back and forth between both countries. He grew up in Provo and went to art school in Mexico. Rojas went to art school in Mexico and would bounce around between Salt Lake City, New York City and Seattle. “So, I always have had this sense of belonging and not belonging,” Rojas explained in an earlier published interview with The Utah Review. “As a person who has existed in both countries with a perspective on the respective cultures as an outsider who does not necessarily belong in one or the other, I learned to appreciate this sense by developing a critical eye to both.”

This sentiment emanates through every work in Coyotek. Created in 2010, the Mexican American Flag (In dependence) is a visual that precisely embodies a statement from Jorge Ramos, a Mexican journalist who is the best-known Spanish-speaking media personality in the U.S., which he made in a broadcast documentary nearly a quarter of a century ago: “The presence of Latinos and immigrants is transforming the lives of Americans in this country. It is a change in the form of how all Americans will live on a daily basis and it is obligating serious governmental negotiation between the United States and Mexico.” To wit: gallery visitors are invited to take a copy of the flag for their own use, as well as post their thoughts and sentiments on copies posted in the exhibition.

In an eight-minute video ‘selfie’ from 2019, Cherry Picker, Rojas reclaims a racial slur he heard during his childhood, one commonly associated with migrant workers who picked crops in the field. In the video, filmed in his kitchen, Rojas starts by eating a cherry and each produce item successively becomes larger. Few may know that in 1965, the U.S. federal government sought to replace Mexican migrant farm workers, who had come under the familiarly known bracero program, with high school students recruited in a project called A-TEAM (Athletes in Temporary Employment as Agricultural Manpower). As journalist Gustavo Arellano noted in a retrospective, the program quickly failed. In the Salinas Valley of California, 200 teens from New Mexico quit after just two weeks, complaining they were broke while students elsewhere staged strikes. The project’s immediate failure was documented in Lori A. Flores’ award-winning 2016 book, Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the California Farmworker Movement.

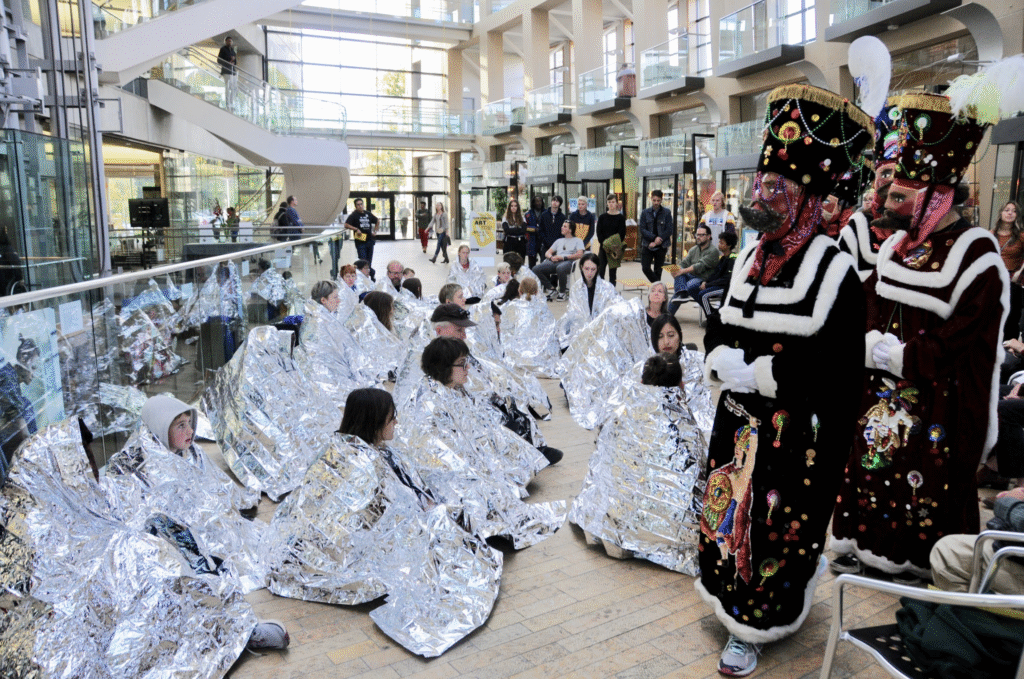

Other performance videos have political overtones. In cage, from 2019, made during the first Trump Administration, the nature of the performance actually seems even more urgent and dire, given the unrestrained, unlawful purges of immigrants going on currently and how families are being ripped apart without a scintilla of compassion. The 2019 performance, staged at the downtown Salt Lake City Library, featured Mexican Chinelos, who wear costumes and masks and during certain celebrations such as Carnival were permitted to mock European colonizers. When they arrived, audience members were invited to stand in for the victims and the video periodically cuts to C-SPAN video footage showing legislative deliberations about the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s detention tactics. In tether, a 2019 livestreamed performance at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) for The Immigrant Artist Biennial (TIAB), Rojas is seen being drawn and controlled with a tether by handlers, which symbolizes the sorts of experiences that undocumented immigrants, such as refugee and asylum seekers, have endured.

Organized and filmed during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Dance for our Departed is remarkable for its coordinated logistics, as a performance art video piece commissioned by Ogden Contemporary Arts. Rojas convened a livestream performance of more than three dozen representatives from multicultural groups of traditional dancers from the U.S. and Mexico, including Native American, Polynesian, African American, Asian and Aztec dances. The performance was an opportunity for mourning and bringing to light how extant racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and quality were being exacerbated during the pandemic. However, the dance actually became an artistic expression of resilience and hope.

Where Rojas’ work takes on its most significant strengths is the tacitly acknowledged unbreakable pact between the material and immaterial realms of the twin diasporas at the focus of this exhibition. In Chac Mool, a performance video created for Utah Sites: Performance Art in Utah Landscapes, Utah Division of Arts and Museums, Rojas reflects broadly upon the historical realities of Indigenous migrations across the Americas. Chac Mools are Mesoamerican sculptures, most prominently featured as a reclining figure leaning on its elbows and supporting a bowl, which many believe symbolized slain warriors carrying sacrificial offerings, such as tortillas, tobacco, and incense made to the gods. In this video, Rojas acknowledges Aztlan, the mythical Aztec homeland, which some historians have postulated could have been Antelope Island on the Great Salt Lake in Utah, near where Rojas documented this performance. Aztec legend is not detailed about Aztlan’s location, except to note that it was north of Mexico on a small island in a lake.

Rojas takes full advantage of the Gittins Gallery space, but the impact is greatest in the section of the gallery that features the commissioned coyote corn mandala in front of the photographic installation, Oh My God, Where Do I Come From. The visual impact is like standing in a chapel. Rojas has arranged the photographs in counterpoint form, as they depict iconographic relics and objects in Mexican Catholic churches as well as pre-Columbian artifacts. The array of these images alerts us to the complexities of the Indigenous cultural realities that were as evident in colonial periods as they are in contemporary times. In the ancient Americas, the ideals of spiritual tributes and sacrificial offerings were universally natural and embedded so it would have made sense that these obligations were reflected in iconographic artifacts, which would have resonated in continuity with those being created during the colonial periods.

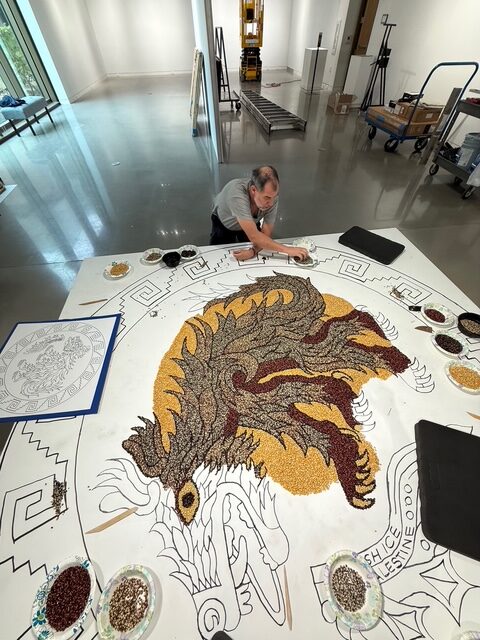

Furthermore, this is brilliantly anchored in the coyote corn mandala installation, the most stunning and most complex of the nine Rojas has made to date. It took five days, with the assistance of five student assistants, to complete the image, which draws inspiration from the Ahuitzotl Shield (Chimalli), a rare Aztec featherwork shield housed at the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna. Dating to around 1500, the shield features a blue coyote and flowing from its mouth is the atl tlachinolli, or “water and fire,” a Nahuatl symbol of sacred war and the cosmic balance of destruction and renewal. With its radiant feathers and gold inlays, the shield was likely ceremonial, embodying divine power and the sacred force of speech and prophecy. The design at the periphery follows Xicalcoliuhqui, or step-fret motif.

A visual masterpiece of the utmost handcrafting, the mandala’s symbolism emanates throughout the installation space. In the mandalas, others of which also are referenced and documented in the exhibition, Rojas has been driven by the sacred geometry that, for example, leads to the ancient symbol of the Flower of Life. It is perhaps the purest icon shared among all ancient civilizations and faiths, rendered by each in their own unique expression. Made entirely of corn kernels placed by hand, the mandala epitomizes an extraordinary exercise of patience. In the one for Coyotek, Rojas also has added text for the first time in two messages: “Abolish ICE” and “Free Palestine.”

While Rojas encourages visitors to come up with their own readings of the piece, the mandala signifies for him the wholeness of his ancestral, familial and cultural roots. One enlightening literary reference comes in the 1949 novel Hombres de Maíz by Miguel Ángel Asturias, the Guatemalan writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1967. The novel is principally allegorical but it also is crafted from the legends of the Kʼiche’, one of the Maya peoples, who inhabit the Guatemalan Highlands, along with the Popol Vuh, the central Mayan sacred text. It is centered around the belief that the people’s flesh was made from corn.

In creating a chapel-like effect in the middle of the exhibition, the placement of the mandala makes sense in front of the juxtaposed photographic collection. As Aleksín H. Ortega explains, Asturias succeeded first at redirecting the reader from a mindset based on Western culture to one rooted in the Indigenous world and then subsequently the parallel constructs “to establish a connection between Mesoamerican mythology and the primitive conceptions of the world recorded in Europe and elsewhere.” Sacrifice is the unifying point upon which Asturias builds the stories in his novel. Ortega adds that this allows the reader to “enter a mythological journey towards the Mayan-Kʼicheʼ worldview. Through this method Asturias manages to demonstrate the validity of this worldview.”

The mandala also deepens our understanding of how Rojas has developed his artistic language over the last 20 years. In the early 2010s, he was invited to participate in Project Row House in Houston, which he described in an earlier interview with The Utah Review as an “amazing place case study utilizing art to deal with issues of gentrification and artists and their role in the community.” At the time, Rojas also had developed a performance persona as the Tortilla Oracle, which arose from more than three decades of reading tarot cards. For the Houston artistic residency, Rojas was asked to augment his performance with a row house project that dove into the history of corn.

Again, inspired by the Asturias novel, Rojas made a corn mandala but also set the stage to create people of corn, made with masa maseca, which had a Play-Doh consistency. Project Row House gave single parents and their children the opportunity to engage hands on in creating the corn people. Meanwhile, as the Tortilla Oracle, Rojas would have the individual place their hands in mixing a ball of masa dough, which would then be made into a fresh tortilla on the spot by community members before he performed the reading. “This led to intimate divinatory conversations,” he added. Individuals also would create their own corn people to reflect themselves or of a loved one whom they missed.

Rojas was inspired by the Project Row House commitment to art as a bridge for making intimate connections in building the community. He continued developing his Gente de Maiz project in 2013, when he prepared an exhibition including a corn mandala, video and Tortilla Oracle performances for the MACLA: Chicano/Latino Contemporary Art Space in San Jose, California.

Visitors to Coyotek will note how these mandala installations have evolved. And, as with the Asturias novel, Rojas had found a way to bring forward an ancient practice into the contemporary era without compromising the essential cultural integrity of its original intent and value. It has been an ongoing process and the Coyotek show is the most synthesized representation of Rojas’ overarching artistic philosophy in this regard.

Tomorrow (Oct. 22, 4;30 p.m.), Rojas will give a lecture in the auditorium of the building housing the University of Utah’s Department of Art & Art History. The exhibition will close on Oct. 29, with a reception beginning at 4 p.m. and a performance by Rojas at 6 p.m. For more information, see the Gittins Gallery webpage.