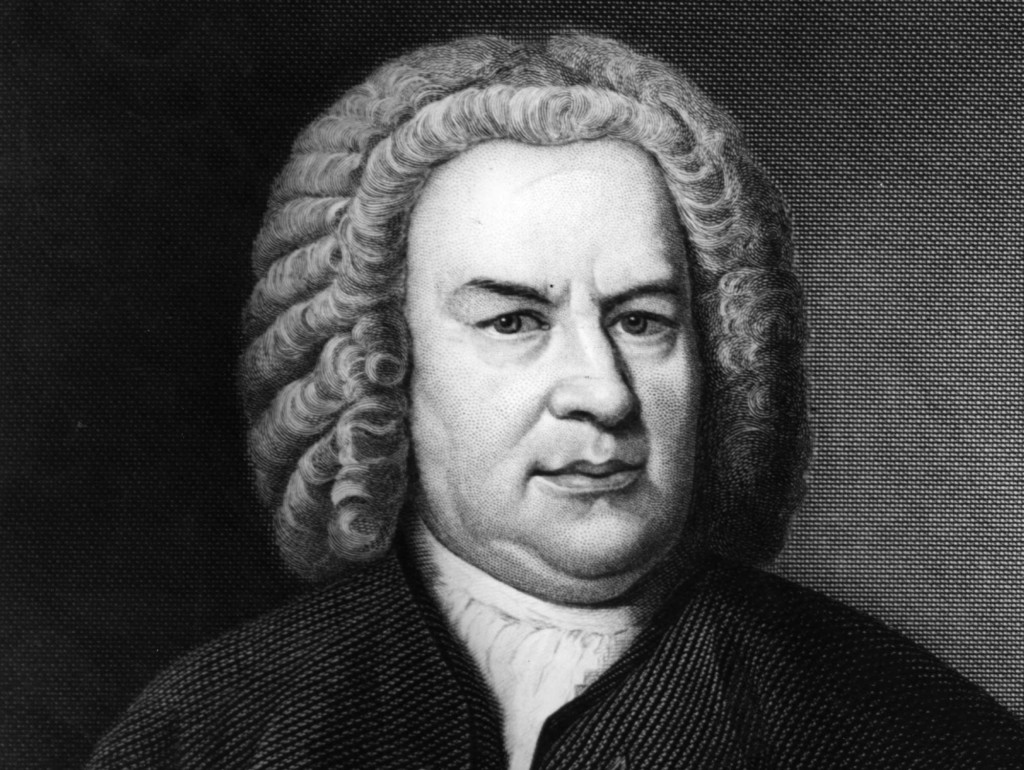

Today, it seems unbelievable to think that in the decades following J.S. Bach’s death in 1750, his music was relegated for the most part to obscurity. Concert life in the 18th century was vastly different from today’s programming objectives, as William Weber, a frequently cited social historian of music, has researched. In 18th century Leipzig, concerts were almost exclusively dedicated to new music — more than 90 percent. In the 1770s, for example, organizers of a London concert series defined music older than 25 years as ancient, which certainly would have excluded Bach’s output. Weber noted that the Romantic Era changed the objectives of concert programmers. By 1870, the Vienna Philharmonic’s repertoire was mostly (85 percent) music by dead composers.

But, as Bach’s music has been resurrected to renewed prominence, musicians and composers continue to be guided by his inventive, adventurous, uninhibited, improvisational embrace of complexities, new sound textures and forms that synthesized a millennium’s worth of musical languages and harmonic vocabularies which had preceded him. For example, the 2010 documentary Bach and Friends directed by Michael Lawrence, offers diverse perspectives from musicians of all stripes who have been inspired by Bach’s legacy.

The NOVA Chamber Music Series’ upcoming Bach and New Horizons concert will offer four works in pairings that magnify the unique NOVA brand of presenting juxtaposed music from the old and the new. The concert will take place April 15 at 3 p.m. in the Libby Gardner Concert Hall at The University of Utah.

The first pairing — intriguingly, husband and wife musicians — features Anne Francis Bayless, cellist of the Fry Street Quartet, and Brant Bayless, Utah Symphony’s principal viola, performing, respectively Bach’s Suite in G Major for Unaccompanied Cello, BWV 1007, and excerpts from György Kurtág’s Signs, Games and Messages for Solo Viola, which was written over the course of nearly 50 years. Instead of presenting the works in traditional performance order, movements of both works will be woven with each other.

The second half features a work by one of Bach’s sons, J. C. Bach, who wrote Concerto for Piano and Strings in E-Flat, opus 7, no. 5 in 1770 and a new commission by Inés Thiebaut, a visiting assistant professor of music theory at The University of Utah, who wrote Work for Piano and Small Ensemble, which features Jason Hardink, NOVA’s artistic director.

The concert, which is part of NOVA’s 40th anniversary season, carries special meaning for Hardink, who will assume a new role as artistic adviser on July 1 when Madeline Adkins, Utah Symphony’s concertmaster, takes the helm as music director.

Plainly, Hardink wants to leave NOVA’s main spotlight with a virtuosic bang. In his role as artistic director for the last decade, he has finessed the Series’ capacity for provocative chamber music programming that introduces audiences to new music, written especially by Utah composers, that matches up ingeniously with a repertoire of works for smaller sized instrumental combinations, both well known and others not regularly performed.

Thiebaut’s new commission is poised to raise an already high bar when it comes to complexity and virtuosity. When Hardink set the guidelines for the commission, Thiebaut says in an interview with The Utah Review she thought that he “had thought out the program very well.” She adds, “He said that he wants to go out with a bang – ‘make me sweat,’ he said.” Hardink is well known for his command of the familiar as well as new piano repertoire, such as Brian Ferneyhough, a British composer who is one of the most prominent musical artists in pushing the complex demands of musicians to realize new sounds and textures in instrumental works.

Thiebaut understood that the J.C. Bach concerto, a charming galant style work that reflected the young composer’s time spent in Italy as opera seria became the rage, was a virtuosic piece in its own right. The son continued his father’s legacy by consolidating a new form for keyboard concerti.

Thus, Thiebaut set out to write a work that opens with the ensemble players and the soloist essentially in equal sonorities but then the pianist gradually takes over, eventually “dominating with unstoppable force,” as she explains. The structure of Thiebaut’s new piece reminds of the older Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D Major, BWV 1050 which starts out similarly. While there are solo violin and flute parts, it is the harpsichord that eventually breaks away in the first movement with a dazzling and finger-tangling cadenza.

“When he [Hardink] talked about the commission and the instrumentation, it made so much sense for this particular concert,” Thiebaut says. “He didn’t want a traditional ensemble accompaniment and wanted to challenge himself with different sonorities.” While the delightful J.C. Bach concerto is scored for keyboard, strings and two horns, Thiebaut eliminates the high strings in her new piece and opts for low strings and brass instruments, including trombones. There is a tip here to the dark, chocolate-like, sturdy sonorities of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B flat Major, BWV 1051, which excises the high strings and pits two viola soloists against an ensemble of bass instruments and the viola da gamba. It was a daring choice of instrumentation in Bach’s time so the creative sentiments are certainly well placed in Thiebaut’s commission piece.

“I am more connected to the music of the earlier ages — medieval, Renaissance and Baroque,” she explains. “I would skip all of the 19th century which doesn’t inspire me at all.”

Thiebaut, a Madrid native, received her doctorate in composition from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center. With André Bregegere, a colleague, she founded Dr. Faustus, an organization dedicated to the commission and promotion of new music, and she has worked with many ensembles promoting contemporary music, including the S.E.M. Ensemble while living in New York. She also has composed pieces for film and theatrical projects. Her music has been performed by ensembles and orchestras throughout the nation and in Europe. Other commissions include a solo piece for trombone, a violin and electronics work, a piece for prónomo flute and electronics, and a chamber piece for The Cadillac Moon Ensemble, commissioned by Julie Harting and Elizabeth Adams as part of the Anti-Capitalist Concert Series in New York.

Hardink says the first half of the concert, which features the Bach and Kurtág solo pieces for cello and viola, respectively, sets an unconventional plane in terms of what one might anticipate at a chamber music program. Both works generally would be programmed for a solo recital but in this particular presentation – as the movements from both works are played in alternating combinations – the bottom-line effect points to the more familiar experience of a chamber music setting.

Meanwhile, the Kurtág work, which the composer started in the mid 1960s and continued adding to in the current century, comprises 24 fragments for the solo viola. He plays with all sorts of instrumental special effects including glissando and pizzicato – some witty and others frenetic. The fragments vary in length from just a few seconds to a minute, with none longer than five minutes. They function like miniature musical prompts, which makes juxtaposing it with a work that already is familiar to many listeners an intriguing experiment in listening.

For more information ant tickets, see NOVA’s website.