Take the title of one of the four short plays in the premiere audio production of Local Color, and a listener can appreciate the organic commitments that Plan-B Theatre has made in bringing original plays that reflect a more genuine sense of the creative place at the core of the Utah Enlightenment.

For closing out its 30th season, Plan-B could not have chosen more appropriately a production that not only resonates with how its Theatre Artists of Color Writing Workshop has become a natural essential element in its creative mission but also how it amplifies the celebration of Pride Month and Utah’s 125th anniversary of statehood (Thrive125). This is a socially conscious theater in full bloom.

The results of the workshop are four stories that are crisp, formidable and precise for how each writer unflinchingly commands us listeners to rethink the diction and syntax of our human connections and consider a dramatically more enlightened language that rejects the unsatisfactory hollowness of the words we frequently have used to characterize one’s identity (and self). The incisive quality of writing in each short play is so sharp that it pierces through and tosses aside the stereotypes and conventions, which have no place in communities that no longer look the same as they did even just 10 or 15 years ago.

DoLs

Written by Dee-Dee Darby-Duffin, DoLs is set in an east side neighborhood near the Johns Hopkins university campus in Baltimore in 1984. A story about how friendships can be made in an unexpected setting, Julie, a 14-year-old white female, meets Adriane, a Black female the same age as Julie, in a park. Both have skipped school and their first meeting starts by comparing observations of a man who unashamedly was masturbating in the park.

Within moments of meeting, the two new friends dispense with small talk. Adriane says, “Everybody’s got a story, Jules…we’re both playing hooky from school. Hiding in the middle of the park.” Julie asks Adriane about her story. Adriane doesn’t miss a beat and announces nonchalantly: “My mom got a new boyfriend. I hate him and he can’t stand me. No biggie, I’ll get through it. He won’t last long. Now what’s yours?” Julie says her mother just told her that she is a lesbian.

Julie feels awkward after hearing Adriane’s surprised reaction and tries to divert the conversation.by talking about how she likes to visit the university library. But, once Adriane talks about why she doesn’t care for her mother’s boyfriend, Julie takes her time to warm to Adriane’s direct questions and tells Adriane that she keeps a journal: “I write about what’s in my head and what I am feeling and shit like that.” Only after Julie tells Adriane that she does not write about her mom being a lesbian, does she fill in the details. Julie tells Adriane that her mother was adopted and she eventually discovered her biological mother. But, Julie’s grandmother also was a lesbian— a fact that Julie and her mother discovered after the grandmother died and they visited her surviving partner in Virginia Beach.

Julie now appreciates Adriane’s knack for getting to the point clearly and quickly. Adriane asks Julie if she thinks that she might be a lesbian, to which Julie responds that she’s not sure but says it’s not genetic. Adriane responds in a way that immediately puts Julie at ease: “Girl, I know that. I’m just wondering if that’s what has you ditching school, writing in your journal, yelling at men who masturbate in public and sharing all your business with nerdy black girls.” Julie tells Adriane that she imagines kissing boys, which is sufficient confirmation for Adriane: “Because if you were a lesbian, you would want to kiss girls and you would already know by now if you want to kiss boys or girls. You are born knowing. That’s what my uncle told me and he is reaaall gay.”

Julie tells Adriane that her mother said either I go to therapy or attend the Daughters of Lesbians support group, where the attendees do not necessarily have to be gay or daughters of lesbians. Shortly after, Heidi, a Black woman around 30 whom Julie knows from the neighborhood,shows up in the park, wondering what the girls were doing. A DoLs member, Heidi reminds Julie and Adriane that the group is more than about socialism. “Basically, we are just a group of people trying to take care of one another,” Heidi says, “making sure that each one of us has all of what we need and most of what we want.” Darby-Duffin’s script shines a wonderful light on the timeless value of legacy.

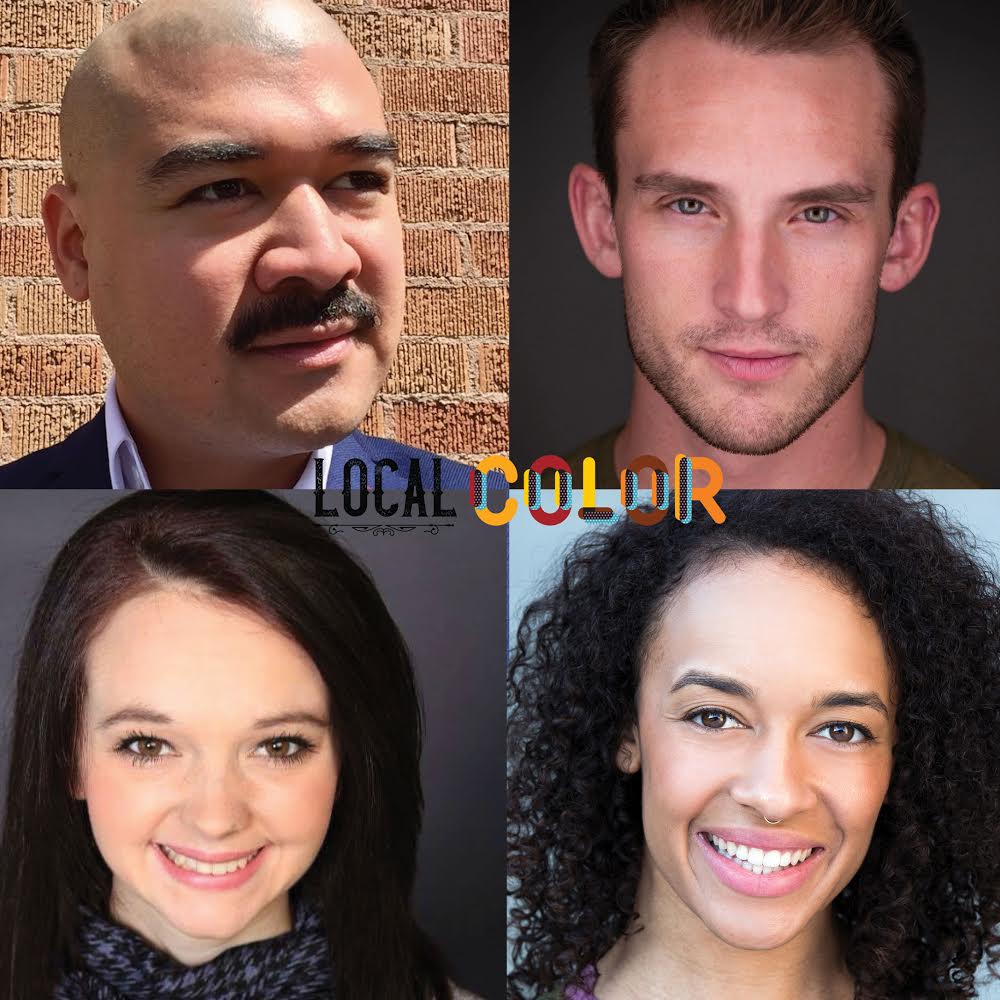

The cast bring out the bounty of charm and sass that animates the script, with Darby Mest (Adriane), Katie Jones Nall (Julie) and Yolanda Stange (Heidi) taking the roles.

LOCAL COLOR Audio Sample from Plan-B Theatre on Vimeo.

Guise

The longest of the four plays (at 19 minutes), Guise by Chris Curlett keeps a brisk pace with wonderful counterpoint surrounding a trio of characters who represent nearly the entire spectrum of how masculinity can manifest itself. Chris nicely frames the ‘bro’ dynamics in the setting of a college gym, from both toxic and corrective perspectives with a lucid grasp on the real and most relevant touchpoints. At the heart of Curlett’s play is Joey, a Black college student in a suburban, predominantly white community (that could be Mormon, conservative or anything similar in the country) who also is coping with depression and anxiety. Rick, who is Joey’s friend, is well liked around the campus and is good-hearted even if he sometimes flakes. Brett arrives later in the play. A narcissist, Brett eventually lets his façade slip, revealing just how racist and homophobic he really is.

In the play’s tensest moments, Curlett inserts sound instructions, including those suggesting labored breathing, an accelerated heartbeat and throbbing musical tones, to signify panic attacks that Joey is trying to control and suppress whenever he tries to confront and manage his greatest fears, insecurity, and those who make racist remarks.

Joey has had a bad week: an argument with his mother, a panic attack in public on campus, a girlfriend who is dissatisfied that he is not working harder toward his potential and the fact that Rick ghosted him on a class project after not responding to calls and texts. At first, the conversation between Joey and Rick appears that it will end badly. Joey tells Rick, “I am saying you do treat me slightly different in mixed company. You become more neutral and colder. So add that on top of me going through whatever and, yes, you change making it hard to get things set straight.” Rick is offended at least for the moment: “Wow. And here I am thinking I was going to come in here and cheer you up. It’s cool. I will leave you in your sadness.”

But, things improve, with Rick genuinely trying to be more empathetic to Joey’s concerns. He also respects the courage it took for Joey to speak openly about the precariousness of his place in a community where he can never be sure who would have his back in difficult times. Curlett draws his characters with sufficient depth that keeps the compact format of the short play. For Joey, the body and self are distinct entities, unlike the privilege of those such as Rick who can afford to believe that both are essentially one and the same.

Brett’s emergence in the play is like a jolt that ultimately strengthens the epiphany that Joey has tried to articulate. Brett tells them, “What you guys up to anyways? Seems like I stepped into a moment or something.” From there, Brett lets his machismo overrun the situation, aggravating the risks of a bad outcome. Curlett masterfully steers the storyline through this brief tumult, leaving properly an open-ended challenge especially for those who truly want to clamp down on the toxicities of masculinity.

The cast delivers superbly on the Guise script, with Lonzo Liggins (Joey), Brian Kocherhans (Rick) and Tyler Fox (Brett) taking on the roles.

Suicide Box

Tatiana Christian’s play is an exceptional example of what the best stories of classic series such as Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits could represent. In Suicide Box, set somewhere in the near future, the story revolves around Lilly, a Black female in her early 30s who always seems to be pessimistic and is socially awkward. She works as a customer service representative, taking calls from customers who purchased online items from a children’s clothing store. There is another character: a ‘tethered’ inversion of Lilly, who espouses the darkest, candid and most ominous dimensions of her thoughts and feelings. This tautly written story also relies extensively on sound design that marks the contours of Christian’s finely drawn character study. In several instances, we hear the voices of Lilly and her tethered version speaking simultaneously,

As mentioned in The Utah Review preview of Local Color, inspired by Futurama, Christian features in her play a device that resembles a phone booth, which the main character enters when he wakes up in the future and attempts to call his family. “But, instead of being able to dial anyone, all these knives come out trying to stab him,” Christian adds. “And it’s revealed that people use that box to commit suicide. So that was the initial idea, and it just kind of spiraled outward to include my experiences of working in a call center.”

Lilly dreads the start of a new work week, save for Naima, a friendly colleague who is eager to share her social media content featuring cats. Naima says, “I kinda want to do a 4/10 so I can have more days off.” Lilly responds, “I can’t wait until we abolish work, so that we can be free to spend our days however we want.”

She dreads just as much the customers who have called to complain, including a woman who claims her shipment was lost, despite that fact it was more than likely due to the customer’s fault. Another is a male customer attempting to use an ineligible promotional code for an order. In both instances, the calls end up going to her supervisor. The ‘tethered’ version of Lilly obviously complicates the matter. Of course, the manager suggests to Lilly that additional training might be needed on how to “de-escalate” such calls.

When Lilly steps out of the office, she meets an individual carrying a sign that reads, “LIVE INSTEAD? LIFE IS WORTH IT?” The individual is protesting the suicide box. She tells Lilly in dramatic fashion, “Yes! Suicide has definitely skyrocketed since these creepy boxes appeared! (Her tone increases in anger as she speaks.) They’re like those fucking electric scooters; one day we were fine, and the next, they’re fucking everywhere!” It’s an outstanding scene, as Lilly talks about her attempt and what compelled her to do so —- and, of course, the “tethered’ voice of Lilly speaks candidly about why.

If there was ever a more astute metaphor for the reason to make the world, in the words of Lilly, “a less shitty place for us to live in,” it could start by revamping the job that has frustrated her with no apparent redeeming value. Job burnout is an occupational phenomenon that the World Health Organization defined as such in 2019 in advance of gathering empirical evidence targeting strategies for improving mental health well-being in the workplace. Likewise, a good amount of management research has indicated that customer service positions such as those in Lilly’s call center fall under the most stressful category. Christian’s Suicide Box encapsulates these themes exquisitely, and accomplishes it in just 11 minutes.

Doing eminent justice to a complex script are Kandyce Marie (Lilly), Darby Mest (Tethered Lilly/Naima), Katie Jones Nall (Caller 1), Carlos Nobleza Posas ((Caller 2) and Yolanda Stange (Manager/Protester).

Organic

Rounding out the podcast is the fast-paced, spicy, naughty, magnificently elucidating Organic. In 11 minutes, Tito Livas sets a story, juxtaposed in two different locations, which raises questions about the politics of outing and whether or not it is justified, depending on the circumstances of the closeted gay individual. But, it also taps into the dynamics of social dating and hookup apps such as Grindr, Scruff, Jack’d and others, which a Slate magazine feature in 2019 described as The New Glory Hole and tensions between those who are out and those who are closeted.

Livas pitches Organic as an apt metaphor for the natural process of acceptance and affirmation of one’s sexual identity and orientation, first by the individual and then by family, friends, lovers, colleagues, etc. In one location of the play, there is a gay male couple – Michael (Hispanic) and Philip (white) – and in the other, there is Joe, a gay Black second grade teacher still in the closet. Michael confronts Joe on social media for not supporting one of his fellow teachers in a public controversy regarding a children’s book about two princes falling in love.

Livas deftly switches from one scene to another (adjusting what was intended to be a live stage production to its present audio format). Joe is at home, going through profiles on the Grindr app for a hookup. Michael tells Philip he is angry about the post from Joe, with whom Michael worked previously. Michael reads back part of Joe’s original post criticizing the teacher’s decision to use the book about the two princes in the classroom. We hear Joe’s voice reading, “that teacher got what he deserved. That material should not be exposed to kids. If you want to share stories about that lifestyle with your kids, do it on your own time, in your own home because that kind of thing is inappropriate and not meant for the classroom.”

No euphemisms about sexual references are in Livas’ script, which amps up the impact of its final scene. Michael recalls how Joe, when they were touring the children’s show, was obsessed with making connections on the apps, even seeking out multiple sex partners on a single night. Meanwhile, we hear the scene of Joe welcoming a man to his apartment. Michael is infuriated by Joe’s utter lack of shame while he continues daring to dictate what he sees as inappropriate for a classroom.

Despite Philip’s best efforts to dissuade Michael from outing him, Michael is adamant, believing if Joe, indeed, was opposed to anything that would signal accepting anything gay related, he would have stayed quiet. Philip responds that perhaps by posting something, Joe might be reassuring those in his family and friends who might suspect that he is gay that he is not. While both men recount their own experiences of coming out, Michael must decide how, and if, he should proceed. What happens at the end is a perfect segue to having a conversation about not only the hypocrisy of homophobia but also how social media technology has reshaped how those who are out and those who are closeted might view and understand more about each other.

The cast takes Livas’ script to maximum energy, with Tyler Fox (Philip), Carlos Nobleza Posas (Michael) and Lonzo Liggins (Joe).

The production team included Jerry Rapier (director), Cheryl Ann Cluff (sound design), Aaron Swenson (graphic designer), Jay Perry (mic technique coach) and David Evanoff (sound engineer).

Local Color will be available for streaming as a podcast on the Plan-B website as well as on its free app. Listeners will be able to access the production within the specified run dates. Tickets for individual productions are available on a pay-what-you-can basis: As a guide, the regular ticket price would be $22 and there are no additional fees. Plan-B will send donation letters to individuals who pay an amount larger than $22 per ticket. For more information, see the Plan-B website.