Five excellent exhibitions, including an outdoor public art installation, are currently on view at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA). The Utah Review highlights each one below.

Something from Everything (through Jan. 3, 2026)

With works curated from 19 artists which incorporate mundane, discarded, routine, and overlooked materials and objects, Something From Everything is an impressive, lucid exploration of yet another iteration in the expandable and malleable medium of sculpture. It was more than 60 years ago when sculptors earnestly began to push the postmodernist boundaries.

This exhibition echoes an important point that Rosalind Krauss raised in a classic 1979 essay about the challenges of mapping the structure and determining factors of an event in art history where sculpture pushed beyond traditional conventions. She wrote that a deeper proving was needed to make comprehensible sense about this movement. This requires, Krauss explained, addressing “the root cause—the conditions of possibility — that brought about the shift into postmodernism, as they also address the cultural determinants of the opposition through which a given field is structured.”

Krauss added that this leads to thinking about the history of sculpture as form differently than with elaborate genealogical trees. “It presupposes the acceptance of definitive ruptures and the possibility of looking at the historical process from the point of view of logical structure,” she concluded. For example, presenting the exhibition’s most extensive multimedia presentation, Nolan Flynn and Patrick Durka offer Realities, featuring ceramics and digital projection, which puts the emphatic punctuation on many considerations raised in the Krauss essay.

Photo Credit: Zachary Norman.

These “conditions of possibility” and “cultural determinants” with their respective emotional, social and historical significance are synthesized into a riveting survey in this show. The show represents work dating from 1959 to the present. Two baseline examples from the earlier watershed period anchor this consideration: Lee Bontecou’s Untitled piece and Charlotte Posenenske’s Vierkantrohre (Square Tubes) from 1967.

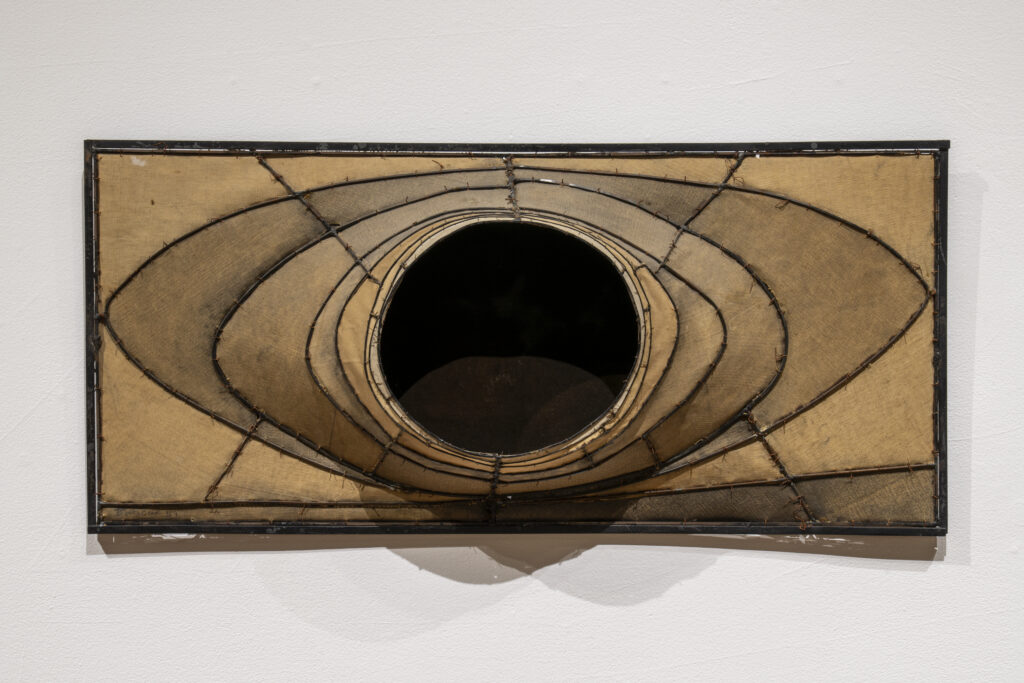

Bontecou’s constructed relief, on loan for the show courtesy of the Art Bridges Foundation, is a paragon of a work that fell somewhere between a painting and a sculpture. This 1959 piece came at the onset of her professional career as an artist in New York City. Designed to hang on a wall, her reliefs were often made from salvaged canvas stretched across or mounted on a welded steel armature. Like other constructed reliefs, Bontecou worked in subdued tones of blacks, browns and grays — all of which create an incredible illusion of infinite, a wholly saturated black void or hole.

This particular relief is considerably smaller than others she constructed, but because Bontecou focused on achieving large-scale effects not through size but rather by the ratio of individual elements to the whole construction. So, in a piece measuring thirty-one inches in length by twenty-seven inches in width, the black hole or dark void appears to occupy a huge imposing space relative to the rest of the relief even when the void itself is really much smaller.

Meanwhile, in Posenenske’s modular sculpture, Square Tubes can be reassembled, rearranged and reconstituted in an endless set of possible reconfigurations for every exhibition display. In fact, when Posenenske sold the pieces to “consumers” — her term for patrons who purchased her work — she gave it at the cost of the materials. Her artistic statement reflected this: “You can proceed according to a set program or you pick individual possibilities according to your personal taste. … After all, there’s enough of them. Don’t worry if you’re never ‘done,’ because the re-combination could proceed in perpetuity without ever becoming boring.” In a similar, Alina Tenser of Ukrainian origin offers her multimedia installation, which includes audio and video projections of a game she created with her son that includes shapes, marbles and water that can be reconfigured in countless permutations.

The most recent works vibrate in contemporary sociocultural relevance. With hair knockers, barrettes, beads and cowrie shells . Ashanté Kindle’s Shall Come to Pass— Lay Your Dreams Right Up to the Sky, 2023–2025 vividly encapsulates her artistic statement:

“Hair has always been a space of freedom and care for me; it’s a place where creativity and autonomy have lived, shaped by personal and cultural histories.” Meanwhile, Leonardo Drew’s Number 264 (2020) looks deceptively straightforward when viewed from a distance, but up close the work, made with wood, paint and cotton and altered by the effects of burning, tearing, oxidation and decay, is rich in its tensions of showing disorder and chaos in the natural of cycle of life, time and historical memory.

Whimsical but also imposing in their inventive provenance, two Sepulture/Sculpture pieces by Ephraim Puusemp are made of birch plywood and were inspired respectively by a child’s dinosaur skeleton model kit and by sculptural ossuaries found in the Czech Republic. The works are slotted and held together by the forces of tension. These pieces are wholly natural and organic.

A native of Louisiana who now lives in Vermont, Clark Derbes is presented by five sculptures carved from felled wood (polychrome maple) and completed with enamel on a steel base. The works emphasize remarkable possibilities for showcasing the materiality of wood.

Ricardo Rendón’s Patrones de trabajo (estados de transformación) walls is unquestionably one of the most striking works in the show, as an example of dematerialization. It is worth comparing Bontecou’s Untitled piece to Rendón’s, who rather than use ratio in scale relies instead on the grand imposing effect of monumental size. Regarding the process of cutting and subtracting the elements of industrial felt and steel grommets, which the artist carried out and installed at UMOCA prior to the opening, Rendón explained his approach in his artistic statement: “I decide to think on the exhibition space as a scenery for work, for example the transformation of the gallery in a working environment, from the walls to the working materials, my practice is determined by the social and physical conditions of the space and its own possible materials.”

This is his modus operandi as an artist: “It consists of determining my subjective reality and setting in motion my creative faculties, which enable the emergence of new understandings. In this way, experience, consisting of the development and accumulation of moments of creation, informs my strategic orientation towards my surroundings.”

With an Americana flair with folk and modernist art tones, Courtney Puckett Seed Series (Slow, eGo, WinD, Hold), comprising found objects and repurposed textiles in sculptures made with plaster and wire are marvelous examples highlighting a well-coordinated logistical expressions of thee aesthetics of bricolage. The same spirit of resourceful industry is found in Sheila Hicks’ Constellation Clairvoyant, where the artist works with synthetic fibers, cotton, linen, silk and other elements as part of her ongoing creative investigation of the materiality of color.

Fabrics in garish colors and how they hang, reflect light, or move or sway when people rush by or when it is caught in the blast from a fan or air conditioner are prominent in Katy Heinlein‘s two works (Double Loser II, Snake Eyes II). Formerly focused in ceramics, Heinlein switched to fabrics as a medium. As noted in her artistic statement. “There was a lack of immediacy. You have to wait for the clay to dry, hope the glaze sets, hope the color comes out the way you want it. You get to see the color in the fabric right away; there’s a certain kinetic energy.” Heinlein adds fodder to the impetus in Krauss’ seminal essay when she said in an interview published elsewhere: “I think a lot about that Barnett Newman quote, ‘Sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to see a painting.’ I relate more to painters than sculptors, but I’m also kind of poking fun at painting. It’s static and one-sided, while there’s a passive kinetic quality to fabric soft sculpture. I want people to walk around my pieces and really engage with them. Be curious and look at all the angles.”

From Senegal, Samuel Nnorom created Something Fishy that touches upon and neatly synthesizes themes of colonialism, fashion waste, the conscience of responsible consumerism and the historical integrity of a community’s social fabric. The artist works from Dutch wax prints or African print fabric (Ankara) and the prevalence of second-hand or used clothes (Okirika). To put the nuances on the thematic interpretation of what is meant by the “fabric of society,” Nnorom’s fabric sculptures metaphorically incorporate “bubble forms, bindle forms, lines of fabric strips, exploded bubbles, and tied clothes on architectural structures or canvases using techniques such as cutting, rolling, stitching, tying, and installation.”

An interdisciplinary artist with roots in northern Mexico and the Rio Grande border, Diego Mireles Duran vividly captures the liminal dynamics of border culture with Huitlacoche Chair, made of calcite, resin, chrome finish and steel. The “huitlacoche” reference is evident in the display of the stools in pieces, ordered in a form that echoes with that linked to the corn fungus which is prized and revered in Mexican and Indigenous food cultures. Furthermore, the stool legs are modeled after the craftwork in cowboy boot stitching. Duran’s work arises from, as the artist describes, “chaotically conglomerating motifs such as 90s Mexican pop and Noreño Music, Mexican candy, traditional artisan practices, and even home cleaning products of their youth such as “Fabuluso”.. ” I want my output to represent what liminality feels like to me. I want it to feel like a long lost word landing at the tip of the tongue.”

Among the smallest sculptures in the show, made from painted scraps of wood that have been glued together, come from Damien Hoar de Galvan, with a half-dozen that resemble heads, boxes and other vessels while still characterized as abstract work. In an interview with a Boston publication, the artist explained that he does not start a work with the final shapes decided and allows the process of creating the as well as his own mood and psychological state of mind at the time dictate the eventual outcome. “I think that if art isn’t mysterious it’s not very interesting. I don’t go in with a particular agenda when making. I don’t think its a stretch to say that these days the world we are all living in is confusing, frustrating, absurd and hilarious,” he said. “There doesn’t seem to be a clear way to understand or process all that is happening at such a rapid pace. In some ways, I feel that these small, slow sculptures are my way of dealing with my life in this crazy world. These ‘vessels’ contain all my emotions and thoughts in response to everything, positive and negative.”

Cultural value, its liminal nature and its metamorphosis over time are dynamically explored in Derrick Velasquez’s pieces: Lacunarium (8-bit), made of glass, lead and birch; Fragment as Ruin (Black and Red X #1), comprising resin, bonded Yule Colorado marble, black aquarium sand, San Joaquin River Delta magnetite and Colorado Red Sandstone, and Untitled 469, made from vinyl and maple. As with the other artists in this show, Velasquez’s sets of possibilities push the expressive potential of sculpture into fluid interpretations that challenge conventional thinking about the meaning behind the work’s materiality.

Just as compelling is Lars Call’s Trapped, constructed entirely of classic mouse traps that have been set, which contends with the topic of gender dysphoria; Marissa Albrecht’s pieces, composed of found road reflectors placed and arranged specifically, molded pulp produce dividers and cardboard produce boxes, that signify the bureaucratic processes of control and regulation in our lives and society.

William Cobbing: Inner Horizon (through Jan. 3, 2026)

An outstanding supplement to Something From Everything, the multi-channel video installation in the Codec Gallery by London-based sculptor William Cobbing, which UMOCA commissioned and marks the artist’s first U.S. solo exhibition, offers a game-changing perspective on how we might view some of Utah’s most iconic lands.

Desert sites such as Stansbury Island, Goblin Valley and Temple Mountain are viewed through first-person camera footage and the overall effect of the viewing experience is as meditatively soothing as if one was actually at these incredible land sculpture formations.

As for the artist, there are two head mask covers made from clay: one with a mirror and the other with eyeholes. It is worth going back and forth between the projections on the opposing walls to get as close as possible to the experience that Cobbing found when he was at these sites. The mirrored head covering shows the terrain, clouds and natural living while the other mask opens up to a full ASMR effect in traversing the landscape. There are very brief moments showing art by Nancy Holt (known for Sun Tunnels) and Robert Smithson (Spiral Jetty) that incidentally connect the familiar to the possibilities of what new perspectives bring in terms of a more purposeful connection to Utah’s extraordinary landscapes.

Oscar Tuazon: Salt Lake Water School (through Sept. 27)

Salt Lake Water School, a modular installation on the Abravanel Plaza, adjacent to UMOCA, is an open-air teaching moment of sort where individuals can explore a variety of text materials that summarize and clarify the Great Salt Lake’s environmental, cultural, economic and historical dimensions of its indispensable value and the cause to rescue and preserve this troubled body of water.

Oscar Tuazon, originally from Seattle who now works in Los Angeles, created the installation that is on a smaller scale compared to his much larger Water School project, where the architecture in the installation is inspired by the movement and phases of the water cycle. The fact that it is placed in the heart of the central downtown district that incidentally is about to undergo one of the most dramatic transformations in the city’s history is a striking reminder that the lake’s moment of crisis needs the same volume of urgent attention that planners typically devote to development that does not always lead to the most ideal transformation of place.

The installation is part of an ongoing public art project Wake the Great Salt Lake, supported by the Salt Lake City Arts Council, Salt Lake City Mayor’s Office.

Carlos Rosales-Silva: Mariposa (through Sept. 13)

Known for his monumental murals, Carlos Rosales-Silva offers an exhibition of smaller-scale paintings along with a commissioned site-specific mural for Mariposa, his UMOCA show. His paintings provide viewers an unforgettable exploration of the impact of color theory for art appreciation. Every field and segment of color in his works is not chosen randomly but reflects an astute recognition of its relationship in place to the colors of sections that abut it and are adjacent to it.

The ideals of borders and their interdependent relationships as presented in Mariposa came from the artist’s visit to Santuario Piedra Herrada, a well-known stopover for monarch butterflies during their migration between Canada and Mexico. Indeed, monarch butterflies provide a rallying concrete point to vindicate our a priori convictions about the positive value and benefits of migration and immigration for the human experience.

Our appreciation of these butterflies and the manner in which they inspire such richly colored abstract works have the power to unify and overcome the utterly dysfunctional polarization that has wreaked so much damage on these issues. Rosales-Silva cleverly tucks a good deal of healthy and meaty substance about the naturally hybrid nature of borders into his work that subtly alerts the viewers to reconsider and celebrate the very essence that is at heart of Mariposa.

Josh Winegar: Future Monuments (through Sept. 13)

Making for an enlightening tangent to the Something From Everything exhibition, Josh Winegar’s Future Monuments comprises intricately constructed black-and-white photographic prints that show how once glorified sculptures and monuments can be manipulated and twisted to reveal the ugly truths and blunt realities of their historical provenance and legacy.

Winegar’s exhibit pops with a realization about how history repeats itself and does so because successive generations consistently fall short of heeding the lessons to ensure that the worst of history is not repeated. Once again, we are reminded of the considerations in Krauss’ 1979 aforementioned essay about the expanding field of sculpture. She noted that the late 19th century signified the starting point of the dismantling of the logic of the monument. The most prominent examples early on were Rodin’s Gates of Hell, which originally was intended for the entrance to a new decorative arts museum and his statue of Balzac, which was intended to be installed in Paris to honor one of France’s most widely known literary personalities. Both commissions went unfulfilled and eventually multiple versions of these so-called monuments ended up in museums around the world.

As Krauss explained, “the Balzac executed with such a degree of subjectivity that not even Rodin believed… that the work would ever be accepted.” Emphasizing its trait of “homelessness,” Krauss characterizes the “monument as abstraction, the monument as pure marker or base, functionally placeless and largely self-referent.” Hence, Winegar’s meticulously constructed photo prints invite precisely the same speculation that the sculptors in Something From Everything encourage viewers to engage in without being directed in how to interpret and process their viewing of these photographs.