When Passing was published in 1929, Nella Larsen’s literary career was on the cusp of greater visibility. She had dedicated the novel to Carl Van Vechten and Fania Marinoff, white patrons of Harlem Renaissance creators. They also had supported the work of Gertrude Stein and other gay writers of the time. Shortly after Passing was published, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first ever awarded to a Black female writer, to support what would have become her third novel – Mirage, exploring characters and stories intersecting Black, white and Latin cultures. However, she never completed the project. No one has ever conclusively determined why Larsen gave up her literary career and returned to her earlier work as a nurse. There were some personal crises. Her husband (Elmer Imes), who taught physics at Fisk University, had an affair with a white woman. There also were allegations that she had plagiarized for a short story but they were never proven.

In recent decades, Larsen’s two main works (including Quicksand) have been resurrected in college literature courses and a fair amount of literary criticism has been published exploring the intersecting issues of racial and sexual “passing” that undergird Larsen’s novella.

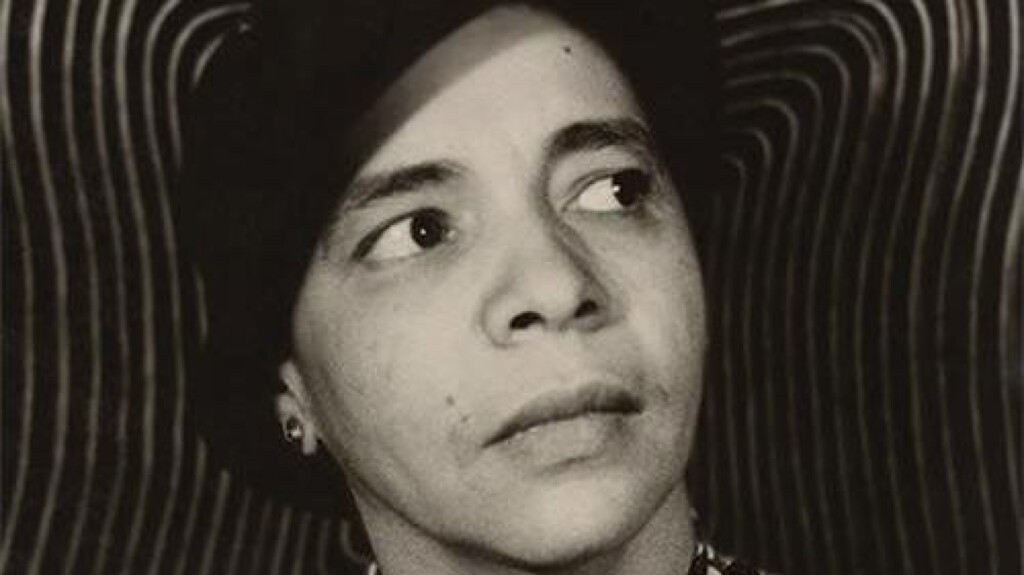

Taking up the challenge of adapting the numerous subtle delineations of the characters and storylines from Larsen’s novella, Rebecca Hall achieves a very good result in the exquisitely crafted film Passing, which received its debut this past weekend at Sundance. Even as a few of the novella’s characters and elements were set aside, Hall, nonetheless, has produced a fidelitous interpretation of the novella with superb production values.

Set in the 1920s, the film opens gradually on a hot summer day in New York City (the film strips out any Chicago flashbacks as described in the novella), as Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson) finishes her shopping and decides to patronize a rooftop café in a luxury hotel. In this scene, the only where Irene decides to pass as a white woman, she is wholly attuned to every element in the dining room and gently tucks her face inside her hat to stay as concealed as possible. Thompson interprets Irene with precise, astute body movement and nonverbal expressions.

As the story unfolds, viewers discover that Irene is a socially conservative woman who is willing to accept and abide by the propriety of an American society where the law of the land at the time was “separate but equal” (although, the unconstitutional realities of that really meant “separate but inherently unequal,” to be determined in the 1954 landmark Brown case before the U.S. Supreme Court). Irene is involved with organizing events for the local Negro Welfare League and always responds to request by Hugh Wentworth (Bill Camp), a white patron who revels in the cultural amenities of Harlem. Irene’s husband, Brian (André Holland) is a doctor who is exasperated and frustrated with racism in the country and wants to move out of the country (this appears in Larsen’s book with him wishing to move to Brazil). Irene is angered when Brian talks to their two sons about racism and violence, including news of lynchings.

When the chance encounter with Clare Kenerly Bellew (Ruth Negga) occurs in the café, Irene is startled by what she sees. Instead of a white woman staring down at her, it’s a childhood friend from her Chicago days. The light-skinned Clare is living her life as a white woman. Her marriage to John (Alexander Skarsgård), an insufferable, pompous racist white businessman, is really a legal fraud (again, not until 1967 when the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Loving v. Virginia case invalidated all laws banning interracial marriage). Clare’s daughter is attending a Swiss boarding school.

Negga’s performance is tantalizing in conveying Clara’s innate adventurous, audacious sense. She also modulates the nuances so naturally when she shows up at Irene’s brownstone home in Harlem. At first, Clare is awkward about communicating her desire to reconnect with the roots and elements that she had rejected previously. Clare’s presence sways Brian and the two Redfield sons and while Irene initially was mesmerized both by Clare and her experience of “passing,” their relationship roils underneath with discomfiting intensity that grows through the rest of the film. Irene worries that Clare is risking too much in coming to Harlem, even if most people have been convinced that Clare is white. Whatever obsession Irene has with Clare though seems to be overwhelmed by Clare’s growing internal desire to liberate the secret that has defined her life for many years. It is this counterpoint that makes the performances of both lead actors exceptional, along with the other cast members.

The actors along with Hall’s direction truly bring as many complexities from Larsen’s writing as possible to the screen without compromising the cinematic narrative structure. Integral to the coherence and cogency are the film’s black-and-white cinescape (shot by Eduard Grau), which is presented in a boxed-in 4:3 aspect ratio, and the sound design weaving in music and the life rhythms of Harlem.

Without daring to spoil the film, the ending echoes an elucidating acknowledgment in Larsen’s own work. She consciously focused on raising and enlightening the rhetoric that for so long had emphasized racial separatism and accepted the racial uplift ideology of black middle-class leaders and influencers, particular from the 1880s to the days of World War I. Whatever uncertainties that permeate and converge in the climax in Passing, Larsen was prescient to know that the fluid nature of history itself hopefully would mean that future generations who read the novella would recognize and understand the intersectionalities at work in race, class and sexual identity that have been just as fluid. Hall’s cinematic presentation succeeds because it sharpens our awareness that within the end of Passing that really what lies beyond is really the same, if not more, of the story’s own beginning.

Geralyn Dreyfous, the cofounder of the Utah Film Center, was executive producer through Gamechanger Films for Passing.

For more information about festival tickets and film, see the Sundance website.