In the late 1860s, the ideal uses, functions, aesthetic value and presence of photography were as controversial as the numerous digital media tools we have accepted recently in our daily lives. Aaron Hertzmann, scientist at Adobe Acrobat, summarized the three views people put forth about photography in the middle of the 19th century. It was not an art form, Hertzmann explained in an essay, “because it was made by a machine rather than by human creativity. From the beginning, artists were dismissive of photography, and saw it as a threat to ‘real art.’’ Another, he added, “was that photography could be useful to real artists, such as for reference, but should not be considered as equal to drawing and painting.” It was the third view that accepted photography as an art form. Hertzmann noted that in “relating photography to established forms like etching and lithography … this group, including hobbyists and tinkerers, avidly explored its potential.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the executives of the railroads turned to ground-breaking photographers to chronicle their massive expansion across the country. Indeed, as the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific railroads raced toward each other to complete the nation’s first transcontinental rail route. And, in Utah, on May 10, 1869, it was completed at Promontory Summit, 66 miles to the northwest of Salt Lake City. That moment was captured in one of the most famous photographs of 19th century American history – East and West Shaking Hands by photographer Andrew Joseph Russell (1830-1902).

That iconic original along with scores of photographs and stereographs documenting the work on the historic transcontinental railroad are part of a magnificent exhibition The Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West, which just opened at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA), located on The University of Utah main campus.

It is the first major event in Utah celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Promontory Summit moment. Throughout the year, numerous state groups plan a diverse spectrum of activities that encompass not only the most familiar aspects of the history but also the lesser known stories that have proven to be as equally compelling and significant for curating a comprehensive, accurate portrait of the period.

The UMFA is the second of just three stops for this exhibition. It was most recently featured at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, where the Union Pacific headquarters are based. Once the exhibition closes on May 26 in Salt Lake City, it will be moved to the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, which during the 19th century served as the home of the Central Pacific headquarters.

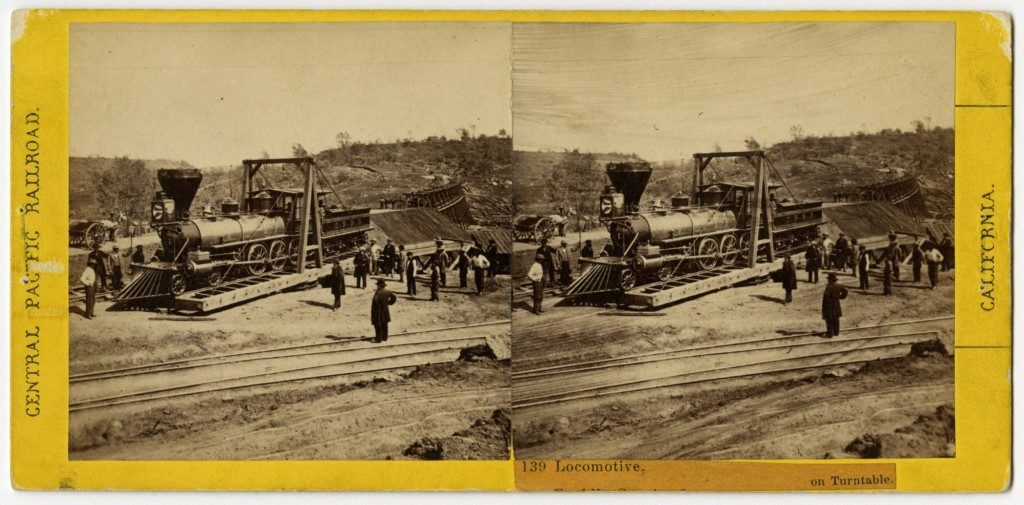

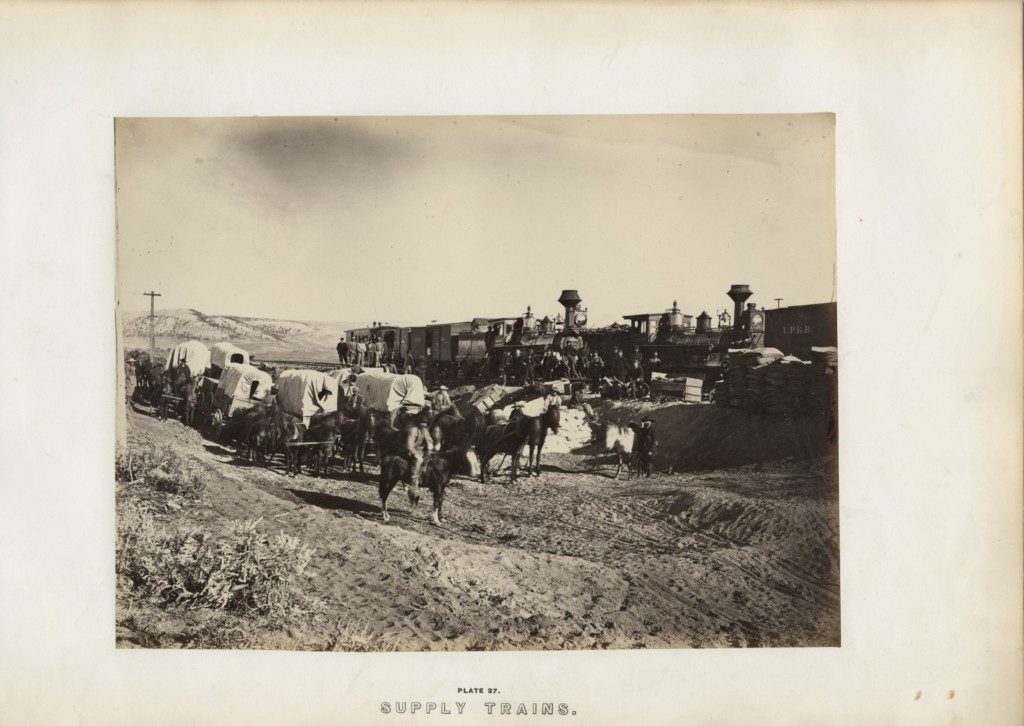

There is a spell-binding aspect to seeing so many rare photographs in one setting, which come from the Union Pacific Historic Collection, located at the railroad’s museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa. There are, of course, numerous, works by Russell, as well as by Alfred A. Hart (1816-1908). Russell was hired by Union Pacific to chronicle the construction westward – a project the railroad executives considered as a promotional platform for investors and others who desired to move and work in the American West. Thus, his photographs are surprisingly understated, a strong counterpoint to the majestic tone that many painters of the American West landscapes pursued in their work. Russell’s photography more than hints at the practical aspects and expectations of daily life and business in a region that would be transformed by the convenience and services of a transcontinental railroad route.

As Micah Messenheimer, assistant curator of the Library of Congress’s Photography, Prints and Photographs Division, noted, Russell had become known for his work during the Civil War. “His charge during the war was to underscore the engineering prowess of the Union as it acquired and operated over 2,000 miles of rail in aid of the war effort,” Messenheimer wrote in an earlier blog post. “For the transcontinental railroad, his purpose was as much promotional as technical.”

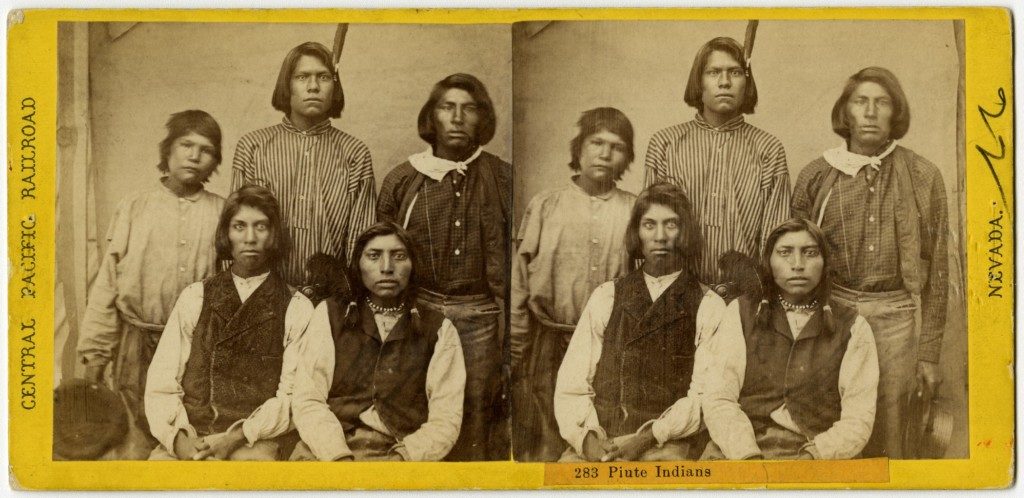

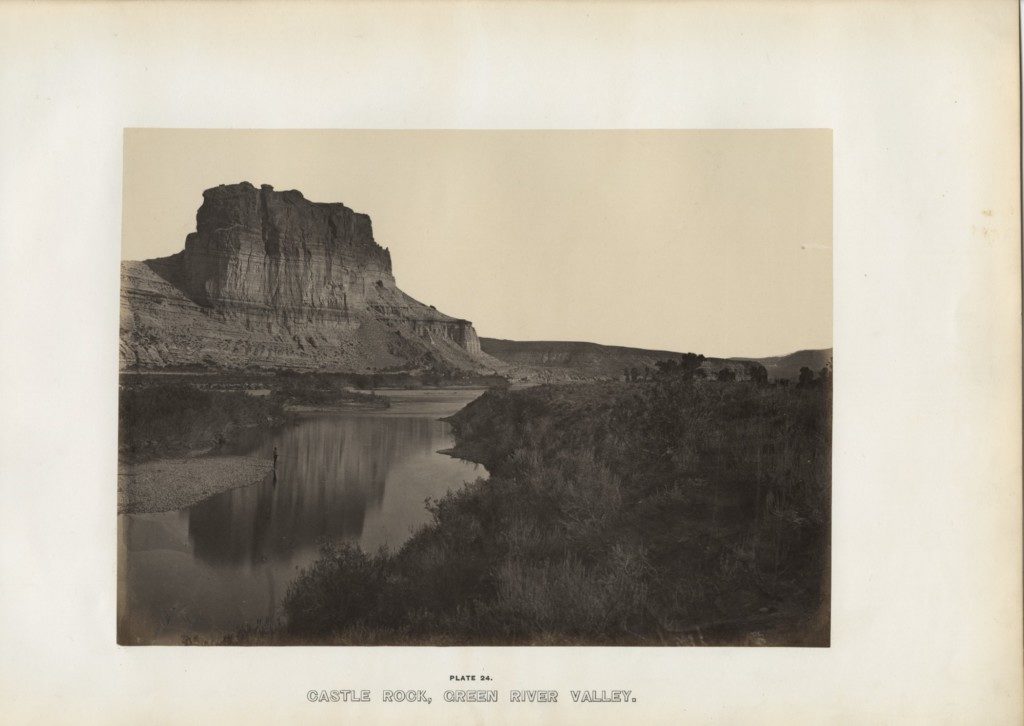

Meanwhile, Hart, working eastward, presents clearly the complexities of this great engineering achievement, not just in the natural obstacles the builders confronted but also the impact on Native Americans and the transformation of a land that would never again be the same. The contrasts in the collection of Hart photographs are striking, especially as Hart moved eastward from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the large flat deserts that soon would animate with adventurous entrepreneurs. In a separate blog, Messenheimer wrote, “Hart’s photographs reflect a more pronounced interest in the technical prowess required to construct the line. This aligned with company interests to assuage doubts that the rugged terrain of the Sierra Nevada could be traversed by a locomotive.”

The exhibition grabs at the tensions of how to contextualize the history of Manifest Destiny not just for its mythologized grandeur but also for the trade-offs that suggest there always is a deep and sobering price being extracted in the name of technological progress and expansion. It is not just mere coincidence that cements the contemporary relevance of revisiting an event that occurred 150 years ago. The transcontinental railroad project was made possible through the work of many immigrants, including those from China and Ireland.

Both photographers captured images of the workers. “In the case of the Central Pacific, these work crews initially were comprised largely of Chinese-Americans already residing in California, and later of laborers contracted directly from China,” Messenheimer explained. Viewers at the exhibition will appreciate how the photographers worked within the technological limitations of their field at the time. As Messenheimer adds, “the wet plate collodion negatives used required long exposure times and movement resulted in blurring. For this reason, most of these images show activity at a pause.”

The environment of indigenous tribes in the Great Plains was transformed, largely in part to enacting the provisions of the Pacific Railway and Homestead Act (1862). One cannot focus exclusively on the justifiably remarkable achievement without contemplating the impact that also usurped the rhythm and nature of life that was so vital to the original inhabitants of the land.

The exhibition also includes a strong local component, courtesy of images from The University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections. These are the photographs of Charles Savage (1832-1909), who met Russell in 1868 when the Union Pacific construction crews entered into Utah. Savage, a Mormon who came to Utah from England at the age of 28, captured Salt Lake City in images that fascinate viewers who wonder how the newly settled territory appeared, as the first transcontinental rail route took shape.

The exhibition also reunites—for the first time in Utah—the famous Golden (The Last Spike), Nevada Silver and Arizona spikes that were present at the completion of the route in 1869. There was a fourth spike but that has been lost ever since. The spikes will be temporarily removed from the exhibition for a short time in the spring, when they will be displayed at the Utah State Capitol in May to coincide with the exact anniversary.

Many of the photographs have never been published. Russell’s Imperial plate albumen prints include images that were published by Union Pacific in 1869 just prior to the Promontory Summit completion as part of an expensive coffee-table-style volume entitled The Great West Illustrated, which included 33 views. Exhibition visitors also will have the opportunity to view stereographs in three dimensions with viewers and other aids. The collection includes 108 stereograph cards by Hart.

The UMFA also has scheduled numerous programs dealing with the various dimensions presented by the history of the event. These include interpreting and viewing photographs, the multifaceted cultural impact of the transcontinental railroad, stories about immigrants and how communities and diverse populations were changed by the development in the American West and the artistic aspects of photography.

This is a ticketed exhibition (adults, $17.95; seniors, $14.95; youth (ages 6–18), $14.95, and children under the age of five, free). As always, UMFA exhibitions are free to Museum members; University of Utah students, staff, and faculty; students at public Utah universities; Utah Horizon/EBT cardholders and active duty military families.

Special admission prices for this exhibition are $5 on the first Wednesday and third Saturday of every month. Meanwhile, on other Wednesdays of the month, admission is $5 after 5 p.m. Free admission days for the exhibition will take place Feb. 16 and March 6.

As customary, admission always is free to UMFA’s permanent collection galleries.

For more information, see the UMFA exhibition page. For information about all of the commemorative events for the 150th anniversary, see the Spike150.org website.