Five exhibitions round out the early spring slate at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), including a major exhibition about contemporary political engagement, an exceptional show that translates the literary memoir genre into a visual art synthesis by an artist from the Carolinas, a celebration of queer voices in Salt Lake City, a regionally produced short film about Indigenous culture and history and a meditative installation about grief and healing.

The exhibition Our Wake Up Call For Freedoms comprises an impressive artistic and cultural thermometer of current political tones, sentiments and climate. UMOCA paired with For Freedoms, the artistic and cultural collective, for the exhibition, which includes opportunities for direct participation and involvement by museum visitors. For Freedoms is a bit of word play inspired by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s State of the Union address in 1941. The Four Freedoms speech, as it is now known, was part of the president’s case to persuade the U.S. Congress to aid Great Britain during World War II. Those freedoms, as Roosevelt listed them, were “the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear.”

The exhibition title also springs from For Freedoms’ call to continue the spirit of an earlier movement in U.S. history – Wide Awakes, which was a 19th century antebellum youth movement that used art, song, and public rallies to push for the abolition of slavery. The historical continuity is marked by a digital scan on vinyl presentation of the wood engraving depicting the procession of Wide Awakes movement members in New York City during the 1860 presidential campaign, which was published in Harper’s Weekly, just weeks before the voting. This is supplemented by contemporary art works highlighting Wide Awakes in 2020, by artists including Jeff Vespa, José Parlá, Coby Kennedy, Wildcat Ebony Brown, Amy Khoshbin and Penny Gottesman and Anya Ayoung-Chee

Among the artists who founded For Freedoms, is Hank Willis Thomas, whose work includes flags with labyrinthine designs where the sociopolitical message may not be immediately apparent but it also comes quickly into focus. Thomas excels at the synthesis of metaphorical and literal contexts in making compelling art. For example, the Liberty flag is created from the uniform garb prisoners are issued while the Justice flag is fashioned from remnants of the U.S. flag.

A third is At the twilight’s last gleaming?, an impressive collage of remnants from flags and banners that represent a comprehensive range of the political spectrum and its populist messages. Thomas’ presentation in this particular piece indicates that all of these remnants and fragments constitute who we are as Americans and we cannot dismiss nor ignore the parts that contradict or rebut our own political sentiments or persuasions. Plainly, if we really want to make progress and to reinvigorate a political culture of freedom, we should not shy away from dealing with every fragment of our complicated history.

Thomas’ work has received international visibility, thanks to the efforts of the Kayne Griffin Gallery. In a December 2021 interview with The Guardian, the artist said, “The thing about America: liberty, justice, equality are all terms that come to mind but, for millions of Americans throughout its entire history as a nation, that has never really been true.” He adds, “Looking at prison uniforms and recognizing that the stripes in the uniforms have the same size stripe as many American flags, I couldn’t help but make that correlation between the stars and bars and the bars that people live in all around the country.”

There are numerous artifacts of political participation, including yard signs, reproductions of billboards, the Amplifier display of posters representing a broad range of contemporary political issues and topics, a Meditative Disco in which visitors are invited to download playlists from Soundcloud and a space with books on sociopolitical issues, provided in partnership with the Salt Lake City Public Library. Among the items that pop out in this large exhibition are Trevor Paglen’s 4×6 postcard marked Vote for War (2016), placed on a voter registration form.

The array of multimedia elements augment the 2-D and 3-D visuals with effective punctuation, including Inter Dependence Day (with words by Black Thought, art by José Parlá, animation and editing by Maryam Parwana and music by Black Thought and The Diamond Mine), and Eyes Open. Capes On. (voiced by Black Thought, written by Jason Nichols, directed by Nichols and Felipe Griebel, with animation by Griebel).

The epiphany observation one might glean from Charles Edward Williams’ Black River: Chronicle of a Spiritual Journey is its superlative presentation of how one’s memoirs in conventional literary form would be translated to an artistic installation and exhibition, which excels in capturing the scope of successful memoirs that convey a cohesive story. In chronicling the complicated relationship he had with his father and then the spiritual reconciliation he found as his father evolved into a religiously committed disciple of the Baptist faith, Williams situates elegantly the parallels between Biblical parables and his own experiences.

With many finely chosen elements that subtly enhance the actual narrative details of the artist’s formative life experiences, the exhibition leads the viewer through the journey, beginning with the early pain and cruelty and then the complex yet eventual path toward forgiveness, reconciliation and enlightened meditation. Williams, a native of Georgetown, South Carolina, currently lives and works in North Carolina.

The exhibition does not include title cards or labels, a not-so insignificant decision about its installation because it wisely conveys the most effective and impactful presentation of the memoir in visual art form. There are photographs, videos, paintings and stacks of the Bible (King James Version) but there also is the installation of a tree trunk with its roots exposed and a small bundle of branches adjacent to it, which would have been used for versatile purposes from heating or cooking to creating a stinging switch for corporal punishment and discipline. The exposed trunks and roots also convey the heft of the metaphor of excavating and coming fully to terms with the experiences of the family and formative years.

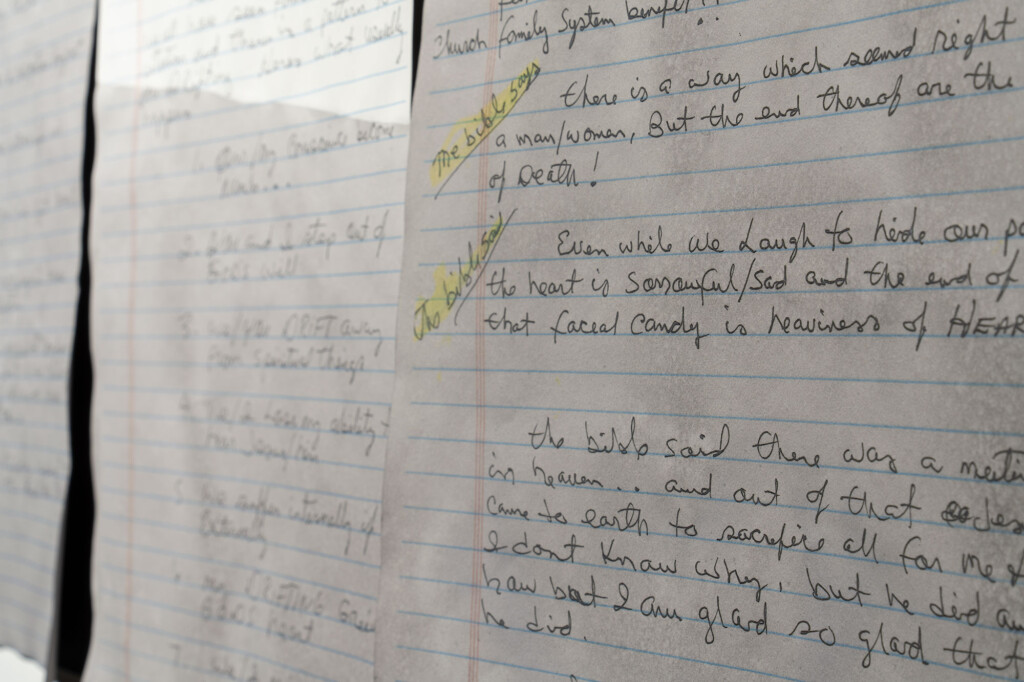

But, the most striking element is the wall of sheets of paper on which his father wrote out his sermons in long hand. Portions of the many sheets of paper are variously covered in black stains, symbolizing the Black River and the baptismal act. In its literary form, a memoir becomes complete when the author includes the dialogue and words of their subject. Viewers should take at least several minutes to scan and read the hand-written sermons. They provide the essential interior dialogue and monologue that are critical to completing the memoir, a literary form that Williams has interpreted superbly in his exhibition.

The latest video in UMOCA’s Codec Gallery is Shattering The Pictures in Our Heads, filmed and produced by the nonprofit Edge of Discovery Co-Creation Studio. The short film, which is recommended to be viewed in its entirety, is presented on three screens and incorporates a 360-degree format as well. This has the desired immersive effect for viewers, as they become acquainted with the work of students from the Owyhee Combined School to capture the language, history, and culture of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes, who currently reside on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation.

Such films achieve so much more of a cultural impact for elucidating perspectives that enliven, enrich and animate the standard boilerplate land acknowledgment that many institutions and cultural entities now include regularly as introductions to their programming. This short film, in particular, emphasizes the communal efforts that are gathering to magnify the visibility of an Indigenous cinema canon, especially in documentary form. The tide has shifted toward hopeful impacts. Just recently, Adam Piron, a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk Tribes, succeeded Bird Runningwater as director of the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous Program, which includes The Native Lab as well as the Merata Mita and Full Circle Fellowships to support Indigenous filmmakers. Similarly, Shattering highlights an emerging generation of voices that will continue to displace myths and stereotypes of Indigenous representation in popular culture.

Lilly Agar’s gallery exhibit A Hug Away pops with a warmly colored environment featuring oval-shaped portraits of members of the Salt Lake City queer community. This multimedia exhibit allows the viewer to listen to audio files about the coming out story, as told by the subject of each portrait. Agar’s work springs from their own experiences of growing up in a traditional Catholic family in Mexico and struggling to claim their identity, even as the pain of rejection would make the individual contemplate thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The A Hug Away theme clearly resonates with the stark existential challenges many young people face, especially in Utah, where they often are rejected, chastised or threatened if they do not agree to change their identities or orientation. The stories are told openly.

There also is a convenient link to the artist’s website with numerous resources for members of the queer community to access, along with expanded perspectives from the artist. “Art has always helped me to heal and to confront hard questions, in order to find the answers that need to be heard,” Agar writes. “Art is the space and language that allows me to work with people whose stories need to be told. For this reason, my work is always displayed in an interactive way so my subjects could share their story directly with all of you.”

In a similar vein, Myleka Bevans’ installation We’re going to talk about it provides a creative functional space for accepting and discussing the process of grief, certainly one of the most difficult and awkward for many individuals in contemporary society. The gallery space is transformed into an ethereal venue with abundant pillowy clouds and ambient light that generates simultaneously cocooning and liberating sensations. The space also reverberates with the voices of those who have experienced the death of their children. Bevans created the work, after her daughter, Bridget, died just five days after birth. There is an unexpected soothing sense of comfort in this exhibit.

A linchpin for appreciating the artist’s intentions is found in the Francis Weller 2015 book, The Wild Edge of Sorrow. Bevans achieves a convincing visual interpretation as it springs from a quote attributed to Kathleen Dean Moore, which appears early in Weller’s text. It reads: “Sorrow is part of the earth’s great cycles, flowing into the night like cool air sinking down a river course. To feel sorrow is to float on the pulse of the earth, the surge from living to dying, from coming into being to ceasing to exist.”

For more information about the museum, the exhibitions and public hours, see the UMOCA website.