Power couples always have captured the human imagination. From Adam and Eve to Cleopatra and Antony to the Macbeths and House of Cards’ Frank and Claire Underwood, the idea of power couples has symbolized more than just the model of relationships. The Urban Dictionary explains that “In a power couple, if one person is flawed, the other person makes up for their weaknesses in strength. Together they are the epitome of what anyone would desire in a relationship. They encourage goodness in the world and make it a better place by being together.”

In the pendants – that is, pair of works intended to be displayed together – of Portrait of A Gentleman and Portrait of A Lady (ca. 1555-1565) by German painter Barthel Bruyn the Younger, the meticulous depiction of the aristocratic couple conveys a secular, worshipful tone of conventional gender roles. The artistic result evokes the manner of devotional diptychs prevalent at the time, as Leslie Anderson of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) explains. In this instance, the gentleman is positioned on the dexter side (“right” in Latin) as the “object of the lady’s spousal devotion.” Meanwhile, the woman is turned toward her husband “with hands clasped around a pair of gloves, a pose suggestive of prayer.”

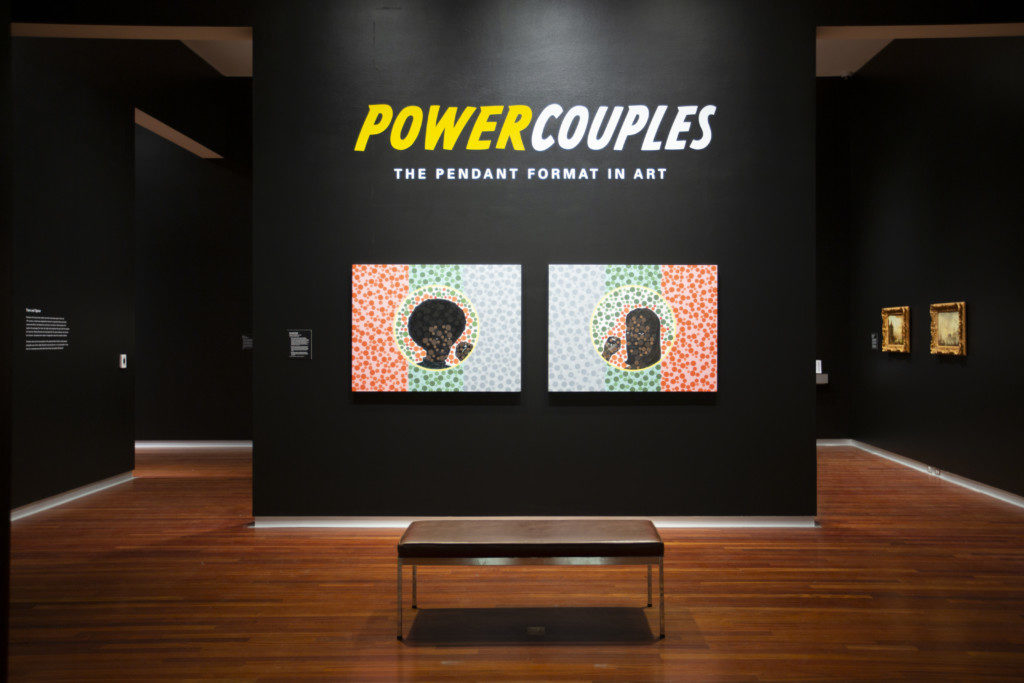

These pendants are the oldest works featured in a new fascinating UMFA exhibition titled Power Couples: The Pendant Format in Art that explores the pendant concept in several significant ways. Curated by Anderson, the exhibition (which continues through Dec. 8) comprises art in various media, spanning the mid-16th century to today. Media include paintings, etchings, prints, sculpture, photographs and video art.

Sixty works represent 36 pairs, including several new acquisitions and a handful of works borrowed from other museums. Many of the works come from the UMFA’s existing collections of European, American and regional art and 28 have not been seen since the UMFA reopened two years ago after major renovations were completed.

The concept of pendants for the exhibition is ingenious, as Anderson not only has curated it to exemplify the representation of gender roles and social status but also to highlight art’s potential intellectual, philosophical and story-telling powers. Thus, one of the exhibition’s three sections is devoted to moments signifying contrasts such as before and after, cause and effect, and departure and return. The third compares familiar stories and philosophical ideals. At several points in the exhibition space, there are interactive, playful opportunities for museum visitors that will enrich their experience.

The Power Couples exhibition is a first-class example of how museums can sharpen the relevant connections to contemporary audiences. Anderson’s innovative approach invites exhibition visitors to a fluid, expansive conversation that dramatically shortens the distance between the past and the present. The pendants in Power Couples offer a mirror, allowing us to see the extraordinary history encompassed in this exhibition and connect it to our own complexities and in our own relationships. Anderson has curated the exhibition so that contemplating the emotional and spiritual paradoxes, as they are displayed, is less intimidating and more accessible. The historical background and contemporary contexts are clarifying, invigorating and enlightening.

There is something for every art lover, encompassing plenty of preferences in style and aesthetics. The variety is exceptional from every period and aspect of thematic treatment in the exhibition.

There are examples of married couples, especially those in the merchant class who enjoyed social and economic mobility, including the early 19th-century oil portraits of the Chandler couple from Vermont by William Jennys (1774-1859). These pendants stand out for their realistic facial features but lack other critical details, such as their hands. Both of them are sitting, positioned in the same direction, unlike the aforementioned Bruyn pendants from the mid-16th century. Anderson explains that Jennys was an itinerant artist who created and sold portraits to couples, making it a decent consumer business.

Meanwhile, from the mid-19th century, Nakamura Geimon I as Horiguchi Gentazaemon in ‘Osanago no Katakiuchi’ and Kataoka Gado II as Tamiya Genpachi in ‘Osanago no Katakiuchi,’ by Japanese artist Konishi Hirosada (1826-1863) portray two Kabuki theater actors. These are notable for the dramatic representations of facial features and gestures. Similarly, these color woodblocks enjoyed strong commercial appeal, given the popularity of Kabuki performances during the Japanese Edo period that lasted until 1868.

Throughout the exhibition, there are plenty of examples highlighting how pendants became appealing for their commercial value. From 18th century France, Nicolas Delaunay (1739–1792) created works of etching and engraving on paper, as adapted from the pendants created by Pierre-Antoine Baudouin (1723-1769). The 1771 pendants La Sentinelle en défaut (The Sentinel Off-Guard) and L’Épouse indiscrète (The Indiscreet Wife) suggest a lot about class distinctions in French society when it came to matters of sexual relations, romance and social propriety. Baudouin’s paintings were well known at the time and Delaunay often created pairs of prints – some with thematic connections and others in contrast – from popular artists of the time, which helped sales in his business.

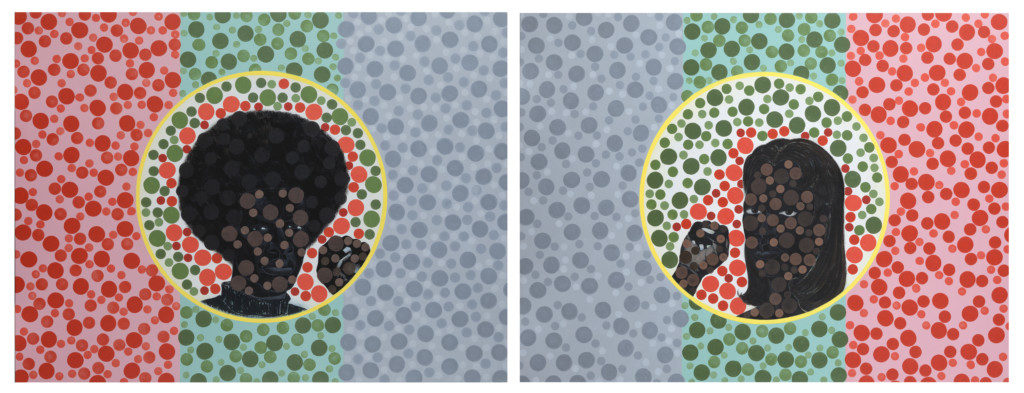

Sociopolitical tones emanate from numerous pendants, especially in how they supersede conventional gender and social status portrayals. Diptych Color Blind Test (2003) by Kerry James Marshall (1955-) is inspired by Marcus Garver’s African flag in its tri-color panels. Marshall inserted portrait medallions with the man whose appearance reminds of Black Panther Party activists during the 1960s and 1970s. And, the woman on right, also is portrayed with the raised fist, the iconic symbol of the Black Power salute. Viewers will note the array of red, green and gray dots in miscellaneous sizes —an effect that conjures up memories of the Ishihara test for measuring one’s capacity to distinguish between colors. Hence, Marshall’s work compels the viewer’s response to the possibilities of a truly color-blind society. This work is on loan from the Denver Art Museum.

One of the featured new UMFA acquisitions, Natural History (2018), by Lorna Simpson (1960-) is a collage highlighting two models from old Jet magazine issues. The pendants riff on the before-and-after images commonly used in beauty ads. The artist overlaid the models’ hairstyles with lithographs of minerals, most prominently, green malachite. That specific color is typically associated with the ideal of inner beauty so their natural hair symbolizes Black empowerment.

Another new UMFA acquisition exhibited is Nina Katchadourian’s Lavatory Self-Portrait in the Flemish Style #20 and #21(2015) that echoes, in part, the devotional diptych dynamic found in works from the Netherlands and nearby in earlier centuries. The artist creates historically inspired costumes with paper products from an airplane lavatory for an impromptu self-portrait session captured in low-resolution photographs, taken on her cell phone. She selected two of nearly 2,500 photographs and video taken on 200 flights. Another Katchadourian pair features molded glass shakers for salt and pepper that Anderson says resembles snow globes. The artist accomplished the effect by using liquid and plastic particles in contrasting colors to signify the seasonings, respectively as purity and pollution. UMFA previously acquired this 2007 work.

Pendants also conveyed the daily rhythm of life in a scene. An impressively detailed glimpse into 17th century life is found in the pair Interior of a Gothic Church by Day and Interior of a Gothic Church by Night, by the Flemish artist Peeter Neeffs the Elder (1578–1656/1661). Presented in oil on copper, these pendants show how churches functioned as the centers of daily life at all hours of the day. The oil pendants of Vue de port de mer (1754) by Charles François Lacroix de Marseille (ca. 1700–1782) document Mediterranean Sea port scenes in which spectators observe a ship depart in the fading daylight and in the companion, fishermen are checking their haul on a cloudy morning, as a ship arrives at port. Viewers also will note the sea conditions at different times of day.

There are several prominent examples of pendants with a strong Utah connection, including some on loan from the Church History Museum of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One pair of oil paintings comes from 1842 by an unidentified artist featuring two citizens of Nauvoo, Illinois: Dr. Windsor Palmer Lyon and Sylvia Lyon (Porter Sessions). Viewers will take note of a waterway that appears to be the Mississippi River, on where the former base of the church was located prior to the settlers moving to Utah. Dr. Lyon ran a drug store that also sold miscellaneous products. The wife also was believed to be one of the plural wives of Joseph Smith, the church founder.

Other pendants have prominent religious overtones.Adam-ondi-Ahman (1893) and Hill Cumorah (1892), by Alfred Lambourne (1850-1926), who was born in England and later moved to Utah) were landscapes inspired by his visit to sites considered sacred by Mormons and were placed in the Salt Lake Temple. Hill Cumorah, New York is where Smith claimed to have received the gift of golden plates by Moroni and Adam-ondi-Ahman represents the Missouri location that Smith contended was where Adam and Eve fled after being expelled from the Garden of Eden.

On loan from the Brigham Young University Museum of Art, one of the most curious pendants from a Mormon collection is The Wise and Foolish Virgin (1856) by Julius Wilhelm Louis (1826–1859), displayed as two separate canvases intended as an altarpiece. Stylistically, it seems to be an outlier for any Mormon art holdings. Also, the artist’s style for these pendants references an earlier period. The pendants portray two women at the time of their wedding. One is perfectly poised, awaiting her bridegroom with one hand pointed toward the heart and the other holding an oil lamp. The other woman is asleep and casual in posture, with the oil lamp hanging precariously from her fingers. Anderson explains the work is a “parable of spiritual preparedness.” Viewers will want to compare the position of each woman in these pendants to earlier works in the exhibition in terms of how devotional, worshipful and spiritual sentiments may have been captured, she adds.

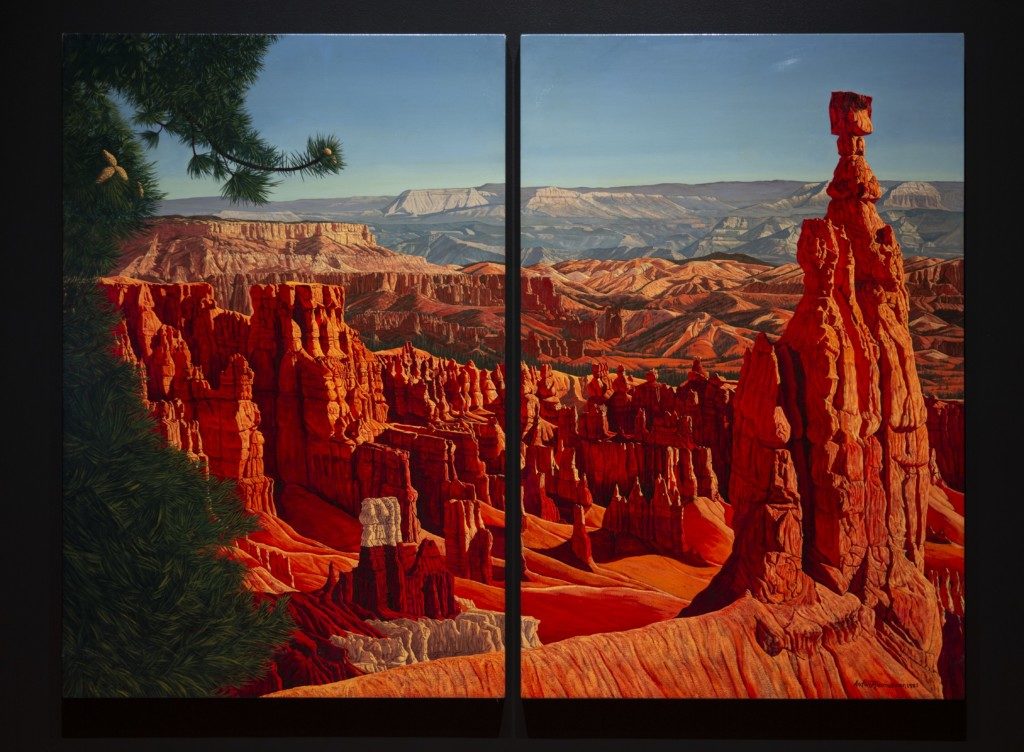

Two more recently produced pairs of pendants highlight Utah’s landscapes. Bryce Canyon (1983) by Anton J. Rasmussen (1942-2015) frames a scene across two canvases including, among other natural features, a coniferous tree and the Thor’s Hammer geological landmark. This spectacular panoramic work should be familiar to many visitors who have ever been at Salt Lake City International Airport. It is on loan from the Salt Lake City Department of Airports.

The other is a pair highlighting Oquirrh Mountains, Bingham Copper Mine and Smelter/Saltair Pavilion, Utah, rendered as gelatin silver prints by Mark Ruwedel (1954-). The pendants summarize the changes from nature’s pristine character to the impact of human activity and commerce. The presentation as a stereograph should stir recall of the recent UMFA traveling exhibition highlighting photographs to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

Nature and landscapes from other vantage points are featured in other pendants. On the Way to Lakeside (1977), by American artist G. Ray Kerciu is an example of his extensive use of lithographs to create 50 iterations of the same subject, as presented in pairs. The work depicts a mountain range, which he observed during an eastbound flight to Michigan. He renders the observations with brown ink on paper in beige, cream and yellow tones.

Becoming a Landscape (9) (1999), by Roni Horn (1955-), is a pair of C-print pendants framing an Iceland hot spring scene at different moments, which may be closer to each other than anticipated. Anderson says the challenge is deciding the direction in how to read the works, because they convey the geologic volatility of Iceland’s landscape. The work also is a new acquisition for the UMFA.

Among the most momentous pendants exploring philosophy and intellectual thought featured in the exhibition come from two brothers who came from a French family well-known as artists. A new UMFA acquisition, the pendants from Augustin de Saint-Aubin (1736–1807) are notable, especially as they were created just as the French Revolution unfolded. The 1789 prints tell a virtually complete tale of a couple’s secret love affair. The woman’s response is represented in Au moins soyez discret (At Least Be Discreet) ant the man’s promise in Comptez sur mes sermens (Count on My Oaths). Viewers also should read the brief footnote Anderson has appended to the display, highlighting an advertisement in a 1789 French newspaper edition confirming these prints were sold as a pair.

The work by Augustin’s brother, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724-178), comes from the existing UMFA collection. These oil pendants – Allegory of Vigilance, Justice, and Law and Allegory of Fidelity and Discretion (1769) – convey contemporary norms about social behavior. Anderson says the paintings, which depict allegorical figures, likely were purchased by a Parisian patron who may have been connected to the legal profession.

Several works have a well-defined pop culture connection. Organizing the Physical Evidence (Purple) (2014) by American artist Brian Bress (1975-) is an outstanding dual-channel hi-def video installation. It’s a convergence of Bauhaus influences, the delightful tone of Pee-wee’s Playhouse and the classic Mr. Potato Head children’s toy. Wearing foam costumes, two characters continuously reconstruct and reassemble their own and each other’s facades. Visitors see two separate broadcasts side by side, but then they should watch closely for how they are synchronized. UMFA purchased this work in 2016.

Another pair of pendants will delight visitors who enjoy the endless bounty of cat images and video from social media. In the late 19th century, the Amlico Publishing Company, a lithography business in New York City, created affordable prints from the oil paintings by Alfred Arthur Brunel de Neuville (1852-1941), a French artist known for his depiction of animals. Anxious Moments and Mixing the Colors (1896) show contrasting scenes with kittens. The left scene shows a kitten gnawing on a bone while the others watch close by, hoping that it will be shared. The right scene shows contented kittens playing. Anderson notes that animals became a popular subject for painters, perhaps in response to French legislation enacted in the middle of the 19th century designed to prevent cruelty to animals.

The exhibition features one pendant separated from its companion, depicting one of the most famous actors of the silent movie era – Rudolph Valentino, as “Caballero Jerezano,” by Cuban-born artist Federico Beltrán-Masses (1885-1949), who worked in Spain. It is a huge painting showing the actor in character as an Andalusian gentleman, although it does not specifically reference a film role he may have had. The companion to this pendant shows Valentino as a Persian ruler during the time of the crusades. The works were separated after the actor’s death in 1926, Anderson adds.

Based on a broad theme readily comprehensible to all audiences, the exhibition is a magnificent introduction to the UMFA’s collection for newcomers and an excellent opportunity for long-time museum patrons to see existing works in a new perspective. It is a deeply gratifying intellectual exploration.

The exhibition run includes several public programs and activities. Free events include art making activities on July 20 (1-4 p.m.), as part of the Third Saturday for Families program, which includes free UMFA admission. Participants can make their own power couples with paint on mini canvases in the Emma Eccles Jones Education Center. A free open studio program will take place Aug. 7 at 6 p.m. and free museum admission.

Anderson will speak about the various themes explored in the pendant format in a free lecture on Aug. 21 at 7 p.m. in the Katherine W. and Ezekiel R. Dumke Jr. Auditorium. Museum admission is $5 after 5 p.m. on that date. Also free with admission will be a Sight & Sound concert on Sept. 18 at 7 p.m., with performers to be announced.

Scholars will participate in a free symposium related to the exhibition on Oct. 4 (10 a.m.-5:30 p.m.) in the museum auditorium. The keynote speaker will be Wendy Ikemoto, curator at the New York Historical Society.

Support for Power Couples is provided by the curatorial sponsor Marriner S. Eccles Foundation and conservation sponsor Ann K. Stewart Docent Conservation Fund.

Entrance to Power Couples is included in the price of general admission. Admission is free the first Wednesday and third Saturday of each month. See the UMFA website for details.