After viewing The Utah Museum of Fine Arts’ (UMFA) largest presentation of Japanese art in its history, one realizes that the best way to think about the sensational works is much broader than the suggested frames of art history often told from either a Japanese or Western perspective. The reasons by which we appreciate, admire and respect the art resonate and enrich our understanding of the assimilating dynamics in a world that seems smaller than ever and where progressive attitudes, ideals and aspirations are juxtaposed against passionate, even intense, expressions of nostalgia for a past that evoke a different sense of pride, identity and glory. These exhibitions also open up revealing historical contexts to observe contemporary Japanese cultural forms including manga, anime, classic cinema and neo-Pop.

The twin exhibitions – one being the museum’s first traveling show of Japanese art (this featuring shin hanga prints) and the other taken from its own collection — underscore UMFA’s curatorial strengths in guiding visitors to discover their own connections to these masterpieces.

The first (open through April 26) is Seven Masters: 20th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints, a show organized by the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) with its tour made possible by International Arts and Artists in Washington, D.C. Curated by Andreas Marks, head of the MIA’s Japanese and Korean art department, the exhibition features a tantalizing mix of prints celebrating shin hanga, which developed during Japan’s post-Edo embrace of westernization while capturing the robust market that traditional ukiyo-e prints enjoyed during the height of the Edo period from the 1600s to the 1800s.

The second (open through July 5) is Beyond the Divide: Merchant, Artist, Samurai in Edo Japan, an exhibition of Japanese scrolls, screens, sculpture, prints and samurai armor and weapons from the museum’s own collection. Curated by Luke Kelly, UMFA’s associate curator of collections and antiquities, this exhibition presents works not seen by the public in more than a decade. These items had been stored prior to the museum’s major renovations, which were completed several years ago.

SEVEN MASTERS

The Seven Masters exhibition highlights a select sampling of artists prominently associated with the shin hanga (new print) movement that revived the woodblock print form of ukiyo-e, which translates as “images of the floating world.” The new wave of shin hanga prints attracted much attention from around the world, mainly because of their exceptional quality and the fact that they were produced in limited quantities unlike lithographic prints of the same period.

Artists resurrected the production elements of the Edo past, including thick mulberry paper and rich mineral pigments, special features such as embossing and mica backgrounds, and an emphasis on texture techniques, such as the swirling movement of the rubbing tool known as the baren.

Traditional ukiyo-e prints, especially after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 when Japan opened its borders to the West, fueled a wave of Japonisme, a French term encompassing stylistic influences that attracted Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters such as Degas, Monet and Van Gogh. The surimono print in the ukiyo-e form was particularly prized, as it typically was privately commissioned and was rendered with the best quality of paper and pigments. Such prints were astonishing in intricate textures that deepened their glossy tones and colors.

As the merchant class expanded, production of ukiyo-e prints became even more popular as affordable pieces of art, with their cost as inexpensive as a noodle bowl for a meal, as Kelly explains. The classic subjects for these prints were Kabuki actors, classic beauties and geishas and Japanese landscapes. In their popularized format and distribution in the commercial trade, these prints could be seen as the precursors of the products of digital publishing that quickly have spread in the 21st century. The viewer will have little difficulty in discerning prints designed for mass commercial use from those that the artists intended to be of especial artistic representation.

Kelly says 1915 marks the “real beginning of the shin hanga movement,” as Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885–1962), the early 20th century role model of the contemporary entrepreneurial publisher, believed the foreign market would respond with strong demand for prints that evoked the Edo-period ukiyo-e aesthetic.

Watanabe was moved by an exhibition featuring watercolor paintings by Friedrich (Fritz) Capelari (1884–1950), and he asked the painter to create a set of print designs that echoed the ukiyo-e tradition. Those prints featured landscapes and Japanese women. When the demand grew, as Watanabe had anticipated, he enlisted Japanese artists to create work for the new shin hanga movement that followed pretty much in step the ukiyo-e tradition. This included the familiar subjects of Kabuki actors, classically beautiful women of Japan and landscapes. Not all of the Seven Masters worked with Watanabe and some artists collaborated with other publishers or published prints on their own.

Kelly says the production of Japanese woodblock prints had changed little since the 17th century (with the exception of sōsaku hanga prints in the 20th century). Publishers had a major role, discovering and employing painters, working with carvers and printers, and then distributing the prints to specialty shops so they could be sold. Thus, market demand was a significant decision point for publishers wondering about the commercial viability of an ukiyo-e print. Watanabe intended to replicate similar market dynamics by working with artists who knew how to integrate classic ukiyo-e traditions and techniques with new perspectives and ideals on the same subjects that had dominated the Edo-period prints.

Among the artists who succeeded at this marvelous blend of traditions and modern expression was Hashiguchi Goyō (1880–1921). There is a 1918 print featuring a model applying white powder on her shoulders, using a hand mirror to guide her. Another is a landscape scene that caught his attention during a train journey from Kobe (Snow on Mount Ibuki, 1920). As noted in the exhibition materials, an impression of this print commanded the highest price at a December 1925 auction of the American Art Association (a predecessor of Sotheby’s) in New York. It was $20 (approximately $292 in 2020 value).

Itō Shinsui (1898–1972) studied as a nihonga painter under Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878–1972), a genre artist known for his images of beautiful women. Shinsui was more interested in representing ordinary working people in his art and joined Watanabe’s new shin hanga movement. Although Shinsui produced designs as requested by Watanabe, he was not fond of the collaborative process involving other skilled artisans in producing the print. His prints include a series devoted to Lake Biwa landscapes and a large-scale series presenting “new beauties,” that were slated to be published in edition runs of 200 with the release of a new print each month over the course of a year. There were delays in the year-long project caused by various reasons, including the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, up to then the worst natural disaster ever to strike Japan.

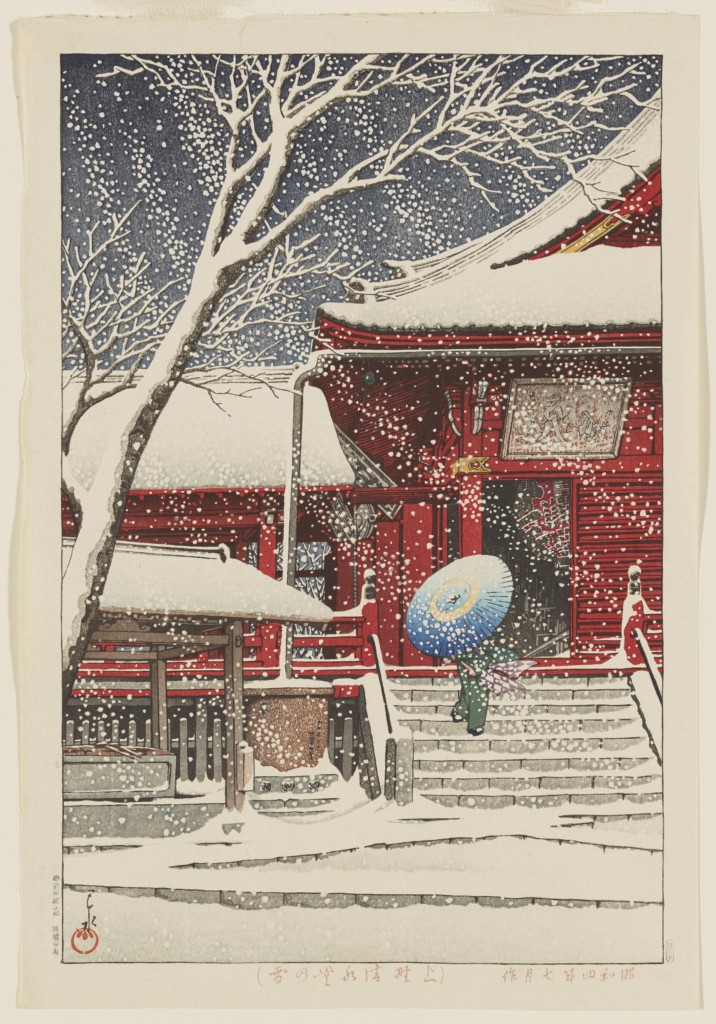

One of the most prolific masters featured is Kawase Hasui (1883–1957), who designed more than 600 woodblock prints. As with his peers, these prints are more sophisticated and elegant than a conventional postcard, showing designs of destinations on Honshu island and the Shiobara village, located in the northern part of Tochigi Prefecture, a location known for its hot springs.

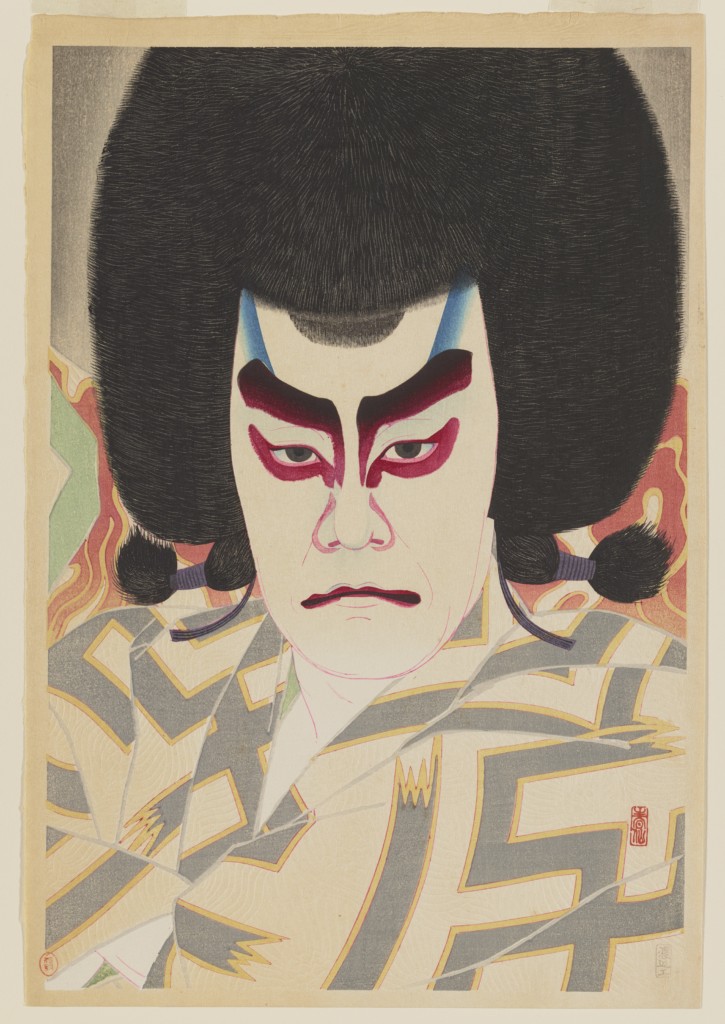

Artists also mastered a recognizable 20th century look in their designs for prints, including Natori Shunsen (1886–1960), who was best known for his portraits of Kabuki actors, as they were presented in both traditional and modern plays of the genre. One features a portrayal of the Ikyū character with a long white beard, an old, wealthy samurai who attempts to thwart the romance between a dashing commoner and a beautiful prostitute from the brother. To reiterate a widely known point, regardless of the sex of the character roles in the play, all Kabuki actors were male.

One of the best examples of the bridge between the oldest and newest traditions, as exhibited in Seven Masters, was Torii Kotondo (1900–1976), whose lineage dates to a venerable family of Edo-period painters and printmakers, led by Torii Kiyonobu (1664–1729). For 300 years, the family had the contract for all of the theater signage in Edo and Kotondo was the eighth person to head the Torii school. However, not until he was nearly 30 did he work with a publisher (not Watanabe) to produce beauty prints from portraits of classic Japanese women. Among the prints is one showing the woman’s undergarment slipping off a shoulder as she applies powder and her hair is arranged in a loose chignon at the nape of her neck.

Like Shinsui, Yamakawa Shūhō (1898–1944) studied with the painter Kiyokata but he only designed one print for Watanabe. Regrettably, much of Shūhō’s paintings were lost, as they had become part of government-sponsored collections and were likely destroyed during World War II. Three prints by the artist are presented in the exhibition. One, a 1927 print published by Bijutsusha, shows a woman’s face in close-up with a traditional shimada hairstyle, which is cropped by the frame. She is wearing a kimono decorated with snow-covered tree branches with red cherries against a gray background.

Another artist who studied classic Japanese painting technique was Yamamura Kōka (Toyonari) (1886–1942), who studied with Ogata Gekkō (1859–1920), a painter and printmaking designer. His name typifies the designation of how teachers bestowed their names on their students. Kōka was the last character of Gekkō’s name and thus became the first of his student.

He followed traditional representations of Kabuki characters but he also deviated from his peers, thanks to the influence of studying the nihonga painting style. This includes a print of a dance hall scene, set in the 1920s at the New Carlton Café in Shanghai, with women wearing Western dresses and bob hairstyles.

Along with these prints, the exhibition includes pieces suggesting how the process of producing shin hanga prints was executed, including pencil drawings and printing proofs. Visitors also should note that the MIA exhibition comes from the extraordinary collection of some 270 prints that Frederick B. Wells III and his wife, Ellen, donated in 2002 to the MIA.

BEYOND THE DIVIDE

The Beyond the Divide exhibition is an unusually good anchor for appreciating the historical roots that led to the rise of the shin hanga movement in the Seven Masters exhibition. Kelly situates the cultural apotheosis of the Edo period (1603 – 1868) as it evolved through the highest aims of the samurai class in balancing exquisitely the tools associated with warfare and cultural enlightenment and later with the rise of a merchant class that sought its own place in society as patrons of the arts. And, in the middle, were the artists and artisans, who rose in status, especially as they developed their creative identities along the realms of established schools and studios which had defined Edo-period culture.

It is an eclectic show of impressive proportions. An outstanding jizai okimono (object of art) is a 19th century steel and silver sculpture of an articulated raptor, set on a perch, with incredible detail in its carved feather and its movable parts.

Another is a pristinely preserved sword with mountings and scabbard (katanakoshirae with saya) and its lacquered wood sheath. The sword from the early Edo period is attributed to Yamato no Daijō Fujiwara Masanori (active 1661–1673) and is mesmerizing in its phenomenal craftsmanship: the sword blade (katana) has its full mounting (koshirae), including handle, sword guard (tsuba), and scabbard. Kelly says while these weapons definitely were made for warfare, a samurai also selected decorative sword mountings with equal care to reflect their persona.

Katana swordplay has enjoyed a resurgence in Japan, especially among young women who have adapted ancient sword fighting skills into physical exercise, as developed by Ukon Takafuji, successor chief of the Takafuji-ryu school of Japanese classical dance.

From a later period, either in the 18th or 19th centuries, a full set of samurai armor is on display, made from steel and iron along with silk, leather, wood hemp and lacquer. It also is an early version of a bulletproof vest, with circular dents that would have withstood the impact of musket weapons that were introduced during the Edo period.

The exhibition presents numerous prints from masters of the traditional ukiyo-e form – a worthwhile opportunity for viewers to compare against the prints in the Seven Masters exhibit. They include Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), among the most widely known of the traditional ukiyo-e artists.

The screens deserve more than a cursory glimpse because of the breadth and depth of detail. From the mid-19th century, Kaiho Yusho II (1818-1869) created scenes from the 11th century Tale of Genji, a fictional story about a prince written by Murasaki Shikibu, a Japanese noblewoman and the source of numerous artistic representations. As one scans the scenes from the right toward the left screen, the prince’s life story easily can be followed from his early years.

Kelly says that each time he views the screens, he discovers something new. “There are so many details within the details,” he adds.

Another captures the astounding formal techniques of the Edo period in the early 18th century – The Four Accomplishments by Kano Tsunenobu (1636–1713). Besides their artistic magnificence, the extensive use of gold leaf served the function of providing more light in a room with the folding screens (byobu). There are countless details on the screens, which stand seven feet tall and measure 144 inches across, each rendered with painstaking exactitude.

Again going from right to left, there are miscellaneous scenes featuring music, calligraphy, painting and a whimsical scene with the game of go (Chinese chess). This is notable because the daimyo lords and samurai followed the “four accomplishments,” as articulated in Confucian philosophy, and incorporated these Chinese principles into their training for the arts of war (bu) and culture(bun). This became a central tenet in the Edo-period’s pedagogy for Japan’s highest family class.

Yet, another screen from 1825 is The Yasaka Shrine, which documents a festival in various scenes featuring at least 300 people. Kelly says that each time he inspects the screen, he tries to find a kimono pattern that has been replicated on more than one figure and he has not yet found an example. The artwork emphasizes the point of how the letters and arts community flourished in Kyoto and elsewhere during the Edo period. Kelly says that, at the time, at least 40 percent of the population would have been literate, adding that there were 183 booksellers in Kyoto alone.

While the Edo rulers did not permit Japanese to travel to China, books and paintings were imported so that scholars and amateur painters could study Chinese art. Kelly notes that some merchant class members became successful Japanese literati painters (known as Nanga artists).

UMFA also has organized several events linked to the exhibitions. These include free art making activities in the Emma Eccles Jones Education Center Classroom including hands-on relief printing (Feb. 15, 1 p.m.) and hands-on miniature Japanese screens (March 21, 1 p.m.) along with an open studio exploration of the four scholarly arts as depicted in The Four Accomplishments screens in the Beyond the Divide exhibition (April 1, 6 p.m.).

Three free, public film screenings will be presented, in conjunction with the Utah Film Center, in the Katherine W. and Ezekiel R. Dumke Jr. Auditorium. These include Miss Hokusai (April 1, 7 p.m.), a 2015 historical manga series adapted in an anime film about the life of artist Katsushika Hokusai, as seen from the eyes of his daughter. Yojimbo (May 6, 7 p.m.) is the 1961 film by Akiro Kurosawa, featuring the story of a ronin whose arrival in a town ends up pitting two rival criminal gangs against each other. Another program is scheduled June 3 but details have yet to be confirmed.

Both exhibitions are supported locally by presenting sponsor George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation, conservation sponsor McCarthey Family Foundation, and programming sponsor Gift in Memory of Hayden H. Huston. Additional support is provided from the Ann K. Stewart Docent Conservation Fund and The University of Utah Asia Center, along with ongoing support, courtesy of the Salt Lake County Zoo, Arts & Parks (ZAP) fund.

For more information about the exhibitions, see the Utah Museum of Fine Arts website.