Focused on tackling the consequences of what remains a large cultural problem that has, as he explains in an interview with The Utah Review, “really dislodged artists and set all of them out in the streets,” Kurt Wenner lived in austere conditions as a young artist – even camping out in a sleeping bag in one of NASA’s defunct wind tunnels – saving up money to go to Rome and rejuvenate the meaning and value of his art education.

While he had generally reached a creative stalemate in his stateside studies, Wenner worked for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, drawing landscapes from the data being beamed back to earth by the Voyager probe and painting conceptualizations of spacecrafts the agency hoped to build and put into service.

In 1983, carefully allocating the money he saved from his NASA job, Wenner found his inspiration in Rome, as he recounts in his 2011 memoir ‘Asphalt Renaissance: The Pavement Art and 3-D Illusions of Kurt Wenner’ (Sterling Signature):

I spent vast amounts of time in the various museums throughout Rome, blending into the silence, which was interrupted by loud tour groups, shouting guides, and shrieking schoolchildren. I was often asked directions and did my best to answer questions in fumbling Italian. Many Europeans stopped to ask where I had studied art, which served to confirm my suspicion that good classical drawing classes were as rare in Europe as in the States. In the many months I studied, I never once encountered an art student or an art class drawing in the museums. The exercises I was undertaking were invaluable and built on what I had studied in school. Unlike life models, the sculptures told stories about the artists and cultures that created them. Merely looking at sculptures does not reveal this information, any more than looking at the cover of a book tells the story inside. Only by drawing them is the formal language revealed. I was finally beginning to obtain the skills needed to compose drawings in the classical tradition.

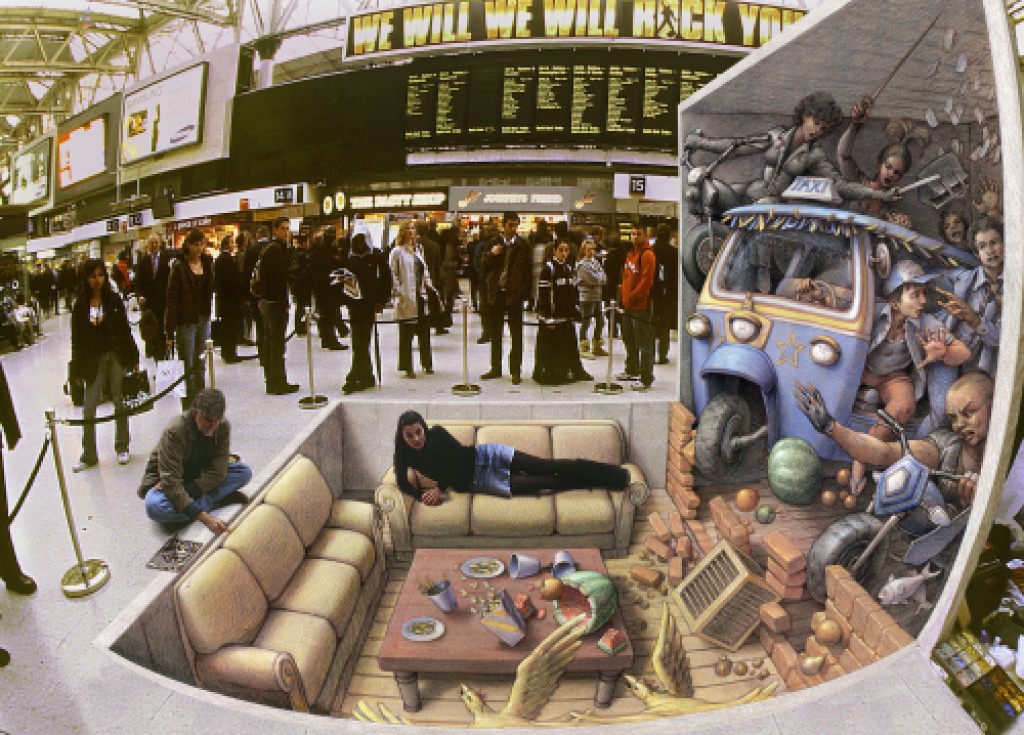

Less than a year later, it was on the Via del Corso near the Trevi Fountain where Wenner soon found his inspiration to invent betts3-D pavement art (two young men were recreating a religious image of Mary and the infant Jesus with thick sidewalk chalks and commercial fine quality pastels), incorporating the principles of the classic Renaissance technique of perspectival anamorphosis. Great artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Hans Holbein the Younger had used this technique with significant impact and which 20th century artists Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali occasionally employed in their work. Wenner quickly cultivated a keen geometric sense of leveraging oblique angles to achieve the once-unthinkable 3-D illusion of creating art that seems to punch up or collapse through the ground level. Drawing upon essentially a Renaissance pool of influences, Wenner began creating art based on techniques and conceptual ideas about perspective from painting, sculpture and architecture.

For this year’s Utah Arts Festival, Wenner will create a unique piece celebrating Utah’s most distinctive sense of place in front of the City-County Building on the Washington Square section of festival grounds. Titled ‘The Sacred Pool,’ he synthesizes elements of the native Ute Tribe and Greek mythology, incorporating the Pleiades, the seven mountain nymph daughters of Titan Atlas, acknowledging the primal significance of the Pleiades constellation in Ute lore.

“I looked up the meaning of Utah and I decided early on to follow the links to other elements – instead of historical – that brought together religious, astrological, symbolic, and cultural strands,” Wenner says. “Central to that is the medicine wheel.”

Focusing on using many strong geometric elements, Wenner will situate a Ute narrative in a desert oasis pool, featuring Sinawav the creator who is surrounded by anthropomorphic figures of the Coyote, Porcupine, Beaver and Buffalo, so key to Ute legend. The images of the seven Pleiades sisters appear to, as he describes it, “rise from the water as floating, transparent figures. The image expresses the global unity of human ideas, which transcend cultural distinctions and seek unity with the natural world.”

Wenner, who usually can accomplish between four and six square yards of detail and work on his large-scale pavement art pieces each day, will start working on site two days before the festival opens on June 25. And, he will continue to add elements and details during the course of the festival, so that visitors can track the progress of the work, which, of course, is an ephemeral piece. Wenner enjoys seeing the images and video clips of his work that people share on social media and the practice certainly will be encouraged during the festival, which places heavy emphasis on the interactive communication of art particularly in an open air setting.

He also will offer demonstrations of his technique twice each day at the installation site. Also in an evening lecture on June 24 (7 p.m.) in the City Library auditorium, Wenner will talk about his path to inventing pavement art and of being reawakened by classic and Renaissance art techniques.

Now beginning his fourth decade as a pavement artist, Wenner typically does a new commission piece every three weeks or so. “I receive about two requests every day but my decision centers on a combination of things, such as funds, logistics, location, etc.,” he says, adding that, on average, he does 12 installation pieces each year.

Before coming to Salt Lake City, Wenner has returned to Italy, where he lived for 25 years and remains a popular figure, to present lectures and workshops. Public education always has been an important component of Wenner’s artistic life. He received Kennedy Center honors for his contributions, in which he set aside one month every year for a decade to do educational presentations about how to work with chalk and pastels for students of all ages.

Wenner’s work is one of the strongest exemplars of how contemporary art has moved well beyond the abstract, heavily romanticized notion of ‘art for art’s sake.’ For example, he says his Utah piece “expresses the global unity of human ideas, which transcend cultural distinctions and seek unity with the natural world.”

There is a distinct expression of social advocacy in his work. Earlier this spring, he created an urban environment piece which compared the dramatic effects of a city landscape under polluted air and a clean sky, which was part of a World Health Organization cultural event connected to a meeting of scientists and experts reviewing measures to mitigate the effects of pollutants for public health and climate change. Five years ago, he created a 4,100-square-foot mural on behalf of Greenpeace, as part of the European Citizens’ Initiative to invoke unprecedentedly their rights under the European Union Lisbon Treaty and to end the EU’s use of genetically modified crops, produce and agricultural practices.

His popularity is uniformly welcomed with enthusiasm across the globe. Regarding a piece he created for the Pier 2 Art Centre in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, more than a quarter of a million lined up to see the art in five days and the sponsor’s Internet site registered more than 3 million hits.

Last fall, Wenner’s major contribution helped establish the certified Guinness World Record for the largest anamorphic pavement art piece — in Venice, Florida, which took 11 days. Wenner’s section of nearly 19,000 square feet (the final 3-D piece highlighting fossils and the extinct Megadalon Shark, measured more than 22,700 square feet).

Wenner’s portfolio is diverse in terms of clients and commissions, both in terms of ephemeral and permanent art. He has created art in Shanghai, Tokyo, Dubai, and New York City, just to name several major international cities. Most recently, he has been tapped to produce art for a new cancer drug. He has created art for Absolut Vodka, Knorr Soup, Champion Sportswear and the Washington State Lottery Commission. Several of his pieces also have been seen in media and film, such as and 18-foot x 18-foot landscape in Westwood, California for the Center West high-rise building on Wilshire Boulevard. Fans of the ‘Sneakers’ film will easily recognize the work. The Vatican commissioned Wenner for a mural based on the Last Judgment that was part of the official welcome ceremony when Saint Pope John Paul II arrived in the northern Italian city of Mantua. The pope signed the artwork.

For the Villa Zeffiro residence in Santa Barbara, which was modeled after the Villa Barbaro in Maser, Italy – a classic example of the Palladio style constructed in the middle of the 16th century – he created more than 3,000 square feet of oil paintings, decorative plaster and architectural details, which were highlighted in an issue of Architectural Digest. His original work and fine prints are carried in several major galleries in the United States, including AFA galleries in Las Vegas, the Andrea Smith Galleries in Sedona, Arizona, and Fine Art Dimensionals in Pasadena, California.

Wenner was the principal artist featured in the 1985 documentary ‘Masterpieces in Chalk,’ which was produced by National Geographic. He also has been featured in extensive broadcast pieces for popular television documentaries produced in Japan and Germany.

What is striking about Wenner’s approach as a contemporary artist is his fidelity and his emphasis on some of the most enduring classical aspects of art history and technique, especially as he incorporates the experience of his work in the science and technical industries. He also nurtures his ability to connect and communicate with audiences, showing why and how art matters in a contemporary society facing unprecedented formidable challenges.

And, for the artist who invented this particular platform of creative visual expression, he continues to fine tune and shape his technique as well as the expectations behind the work. He can effectively accommodate for the quality and condition of the pavement surfaces, knowing how to best infuse colors and rich details into his pieces. Working on pieces which might span several days, he uses an ideal plastic covering to protect the work as best as he can from rain or any other harsh elements of weather. For a brief period, he experimented with paints in addition to his standard assortment of high-quality chalks and pastels, “but paint really doesn’t work on many surfaces that are rough or tend to crack, and not on outside murals,” he explains.

By the time he had already worked 10 years on his pioneering art form, the Internet’s capabilities for individuals to disseminate, share and highlight content and imagery were just beginning to take hold. Today, there are far-ranging and far-reaching digital records of even Wenner’s most ephemeral pieces. Sometimes, the amateur captures are just as impressive as the professionals.

Wenner consistently returns to the larger cultural problem which has global, immersive ramifications, as he deals specifically with how so many people misrepresent, misinterpret, and miscommunicate how to define creativity. Process, not phenomenon, is what should matter, according to Wenner. As with time, space and energy, Wenner says creativity is the (fourth) essential attribute of our physical world. It is creativity that affords humans the capacity to develop complex, sophisticated patterns.

An active, thorough blogger, Wenner wrote in 2012: “Human creativity is distinct from nature because all human knowledge is fundamentally symbolic. Humans must translate experience into some form of language, (this includes mathematics, musical notation and design as well as written or spoken languages), before manipulating it into new combinations. These new combinations of symbols are then expressed as actions or artifacts.” It is only then that all of us, Wenner says, will enjoy a more enlightened relationship with each other, our planet, and with our existential realities.”

No doubt: Wenner’s work and appearance are a perfect fit to the festival’s central theme of ‘Art Lives Here.’