NOTE: All four short films are available for viewing here.

In its 15 years, the PitchNic film program at Spy Hop Productions has succeeded because student filmmakers first learn the rules of crafting a good narrative for a short film, whether it is fiction or a documentary piece, and then learn how to break them, as needed, to serve a specific artistic purpose. One of the most important lifelong lessons the students receive is the instrumental value of pushing their creative and perceptive boundaries to find their authentic voices as a filmmaker.

There are genuine voices and passions of interest in the four student short films that were premiered earlier this month to a packed house at the Jeanne Wagner Theatre in the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. Regarding professionalism in visual quality and production technique, this year’s crop was among the strongest in recent years, thanks to the efforts of the mentors, including Colby Bryson and Alec Lyons, who worked with the pair of fictional narrative short films, and Shannalee Otanez, who consulted with the two documentary teams. In each instance, the student filmmakers found a suitable narrative for distinguishing their storytelling voices.

These four films undoubtedly are ready for submissions to the film festival circuit (more than 90 percent of the PitchNic films have screened in at least one film festival). And, the possibility is strong that at least one or more of this year’s films could find their way onto the internationally curated Fear No Film program of next summer’s Utah Arts Festival.

Dead Air (Steven Uribe, Carson McKinnon and Ryan Leader) came out as an effectively terse, idiosyncratic bit of lyrical poetry laid over a murder mystery, one of the most ambitious challenges of narrative fiction ever attempted by a PitchNic student team. It also is one of the most satisfying scenic short films a Spy Hop team produced, with a good deal of the film shot at secluded spots at the Causey Reservoir in northern Utah. The dialogue is economical to near bare-bones form, but it forces the viewer’s attention to take in various visual cues of foreshadowing that pop up in the short film which ticks in at barely 14 minutes.

The story, set in the 1970s, focuses on a reclusive plein air painter who witnesses a woman’s fall to her death in the distance and has his statements taken by police. One song figures prominently in the film, After You’ve Gone, a song composed in 1918 by Turner Layton with lyrics by Henry Creamer and sung by Marion Harris. In many respects, the lyrics complete the story. One verse stands out:

There’ll come a time, now don’t forget it

There’ll come a time when you regret it

Oh babe, think what you’re doing

You know my love for you will drive me to ruin

After you’ve gone, after you’ve gone away, away

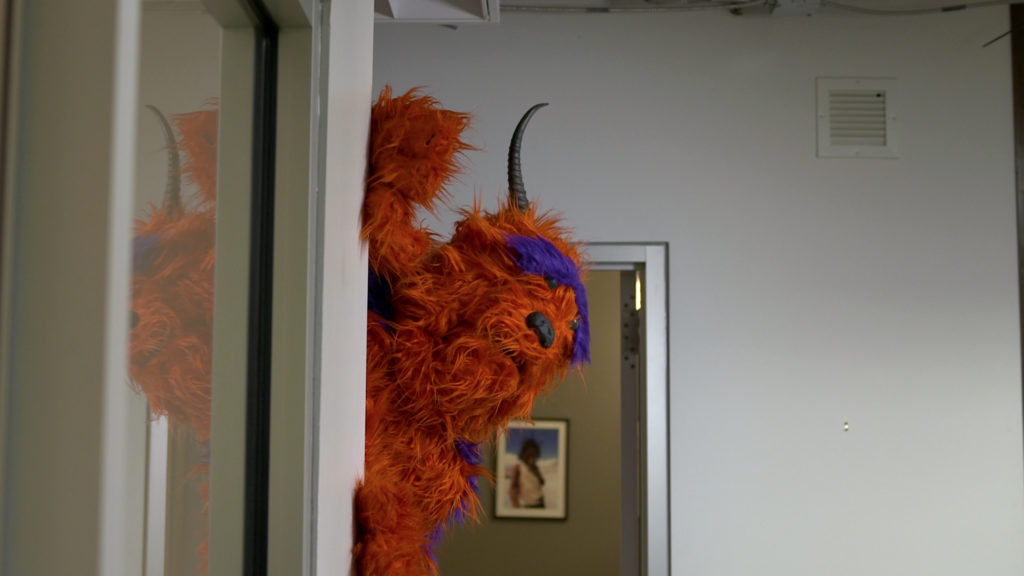

Like its companion fictional narrative entry this year, Hugh (Keiki Taylor, Fate Leaver, Lauren Vernon and Casey Josephson) also set a couple of precedents for PitchNic. The main character is a creature the students built, which rises to more than nine feet in height and whose appearance is a tribute to some of the wonderfully weird characters of children literature. And, unlike other coming-of-age stories that have been made at PitchNic, Hugh presents Dustin, the creature’s treasured human friend in three different stages of his life: childhood, transition to adulthood, prime career time.

But, the epiphany is unexpectedly bittersweet. The short film opens with a solid anticipation of comic possibilities but then it becomes apparent, as the amount of dialogue tapers off, that the story is about the awkwardness and emotional price we endure when we try to uncouple our childhood dreams of magic and fantasy from the serious responsibilities of our adult lives. It is a mature, wise treatment from an enterprising group of young filmmakers.

Living Concrete (Zachary Spier and Brittney Long) is a short documentary film about skateboarding made by teen filmmakers but its transcends the obvious expectations significantly by focusing on an older generation of skateboarders who easily blend in with their much younger counterparts at the parks and cubes. The older subjects – mostly in their 40s and 50s – are grounded, serious enthusiasts who take breaks from their usual responsibilities of adulthood to keep at a recreational sport they have enjoyed ever since they were the age of the kids who now use the parks regularly.

The film thoroughly encompasses the best aspects of Utah’s quintessential skateboarding culture. It also highlights how that culture has evolved from one generation to the next. The men are close to the age of Tony Hawk (now 49), who also is a father of six children. When they were young, the opportunities to become famous and make money off skateboarding were extremely limited. But, like Hawk, the men are respected by their younger counterparts and always are approachable. There are lessons not only about skateboarding but about what trials, challenges, successes and failures of adulthood teach us about becoming respected role models.

An authentic expression of the Navajo Nation’s cultural and sociological values, Native (Isaiah Woods, Annelisa Kingsbury Lee and Grace Riter) is an important positive example of how filmmaking can rebut misinformed and stereotyped perceptions about a community.

The filmmakers grounded themselves in showing the realities of living on the reservation in Shiprock, New Mexico but bookending them with the voices, music and sounds of a community that sees its ancestral and cultural legacies as its most important assets. The young filmmakers focus on empowerment and enhancement, using the voices of community members as well as Russell Begay, the president of the Navajo Nation. Many people might only see media reports in print or online that focus on impoverished conditions or on individuals as helpless.

Native reinforces an informed perspective that champions the intergenerational connections of families as central to the larger Navajo culture. Furthermore, Native, conceptualized by Woods – who is Navajo – exemplifies a new wave of social and political activism and the creative impulse for Native American filmmakers to take control in telling their own stories. Overall, Native resonates in a strategically important dimension of Spy Hop’s larger mission. Programs like PitchNic and Reel Stories, in which students make five-minute short films, provide the digital and media tools of storytelling accessible to young people who become attuned to the importance of representing a truer, more accurate rendering of a specific community’s cultural life and values.