In 1931, as the Great Depression’s grip tightened, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the obituary for the flimsy age of roaring confidence and youth-driven abandon that had been “jolted” out of existence when the stock market crashed in 1929. In an essay titled Echoes of the Jazz Age, he wrote, “It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire.”

He noted the “wildest” generation responsible for the Jazz Age had been “adolescent during the confusion of the War [World War I],” and which “brusquely shouldered my contemporaries out of the way and danced into the limelight. This was the generation whose girls dramatized themselves as flappers, the generation that corrupted its elders and eventually overreached itself less through lack of morals than through lack of taste.”

Silent Dancer, Salt Lake Acting Company’s (SLAC) latest world premiere production, does a solid job in translating this dynamic into a unique staging experience, directed by Cynthia Fleming, with script by Kathleen Cahill, choreography by Christopher Ruud and original music and sound design by Jennifer Jackson. Ruud set the choreography to be integrated seamlessly with Cahill’s scripted dialogue and narrative arc, which is filled with many subtle ironic gems. At many times, the modern dance choreography excels as a striking, original element – a good example of the synergistic potential between contemporary theater and modern dance. However, there are other moments where the execution of the movement on stage feels more like conventional musical theater, which compromises the play’s dramatic pacing.

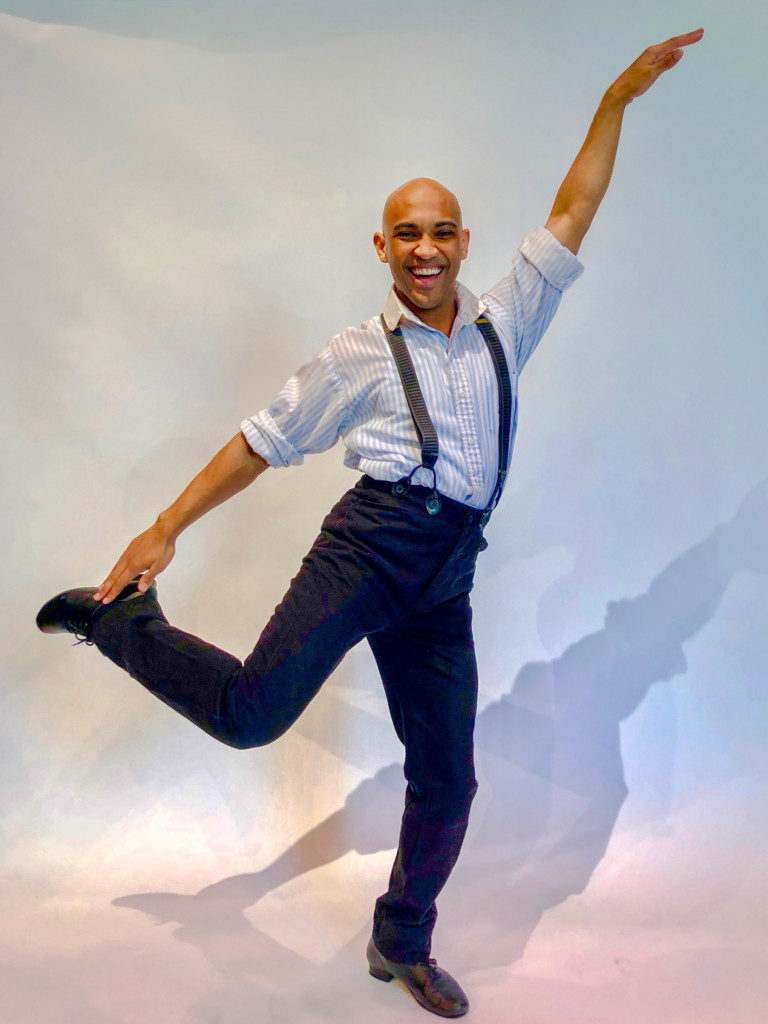

Cahill sets the play in New York City during the early 1920s, the Jazz Age’s most intense phase of heady youthful energy. The two main characters are brother and sister Rosie and Michael Quinn, who strive to jump onto the latest trajectory of social and economic mobility. The city is flush with local production sets for silent films and the siblings take as many opportunities to audition as actor-dancers. The aspiring yet practical-minded ingénue, Rosie (Mikki Reeve) falls in love with Perry Branfield (Darrell T. Joe), a black jazz pianist and composer. Michael (William Richardson), a veteran who has yet to cope psychologically with the horrors of the great war, always borrows money from his sister. In addition, he comes to accept his gay identity.

Silent Dancer, Salt Lake Acting Company. Photo: Joshua Black

Adding to the tension is Jackie ‘Legs’ Diamond (Austin Archer), the quintessential street gangster/bootlegging character of the Prohibition Era. And, then there are the new celebrity darlings of the Jazz Age: F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald (Noah Kershisnik and Alice Ryan, respectively). Rosie works as a maid for the couple.

Cahill leavens all of this with the time-resistant issues and social concerns found in every historical era of revolt, war, cultural shock and recession: immigration, sexual identity, sexual liberation, racism and civil rights. All of it feels historically appropriate and Cahill’s integration of the Fitzgeralds anchors Silent Dancer’s themes with satisfying effect.

Silent Dancer, Salt Lake Acting Company. Photo: Joshua Black

From 1922, Fitzgerald’s second novel The Beautiful and Damned brilliantly rendered the actual scandalous stories about their marriage into fiction. It was so popular that it was immediately made into a silent film of the same name, directed by William Seiter. However, Fitzgerald disavowed the adaptation, calling it “cheap, vulgar, ill-constructed and shoddy,” a point noted in Michael Ankerich’s excellent 2010 book Dangerous Curves atop Hollywood Heels: The Lives, Careers and Misfortunes of 14 Hard-Luck Girls of the Silent Screen. In the later essay, Fitzgerald wrote that film producers were “timid, behind the times and banal” and he blamed, in part, censorship for the incessant “blatant superficialities” of film. The silent film projection in Silent Dancer is a significant prop. As a side note, some of Silent Dancer’s best humorous moments come from scenes of the siblings’ silent film auditions with Archer playing a stereotypical director.

The thematic issues Cahill raises in the script become the springboard for the choreography. Ruud, who is retiring after 21 years in an outstanding career at Ballet West, already has a distinguished reputation as a choreographer. He has received dance commissions from the Utah Arts Festival and has coordinated the festival’s dance commission activities, along with being artistic director of RUUDDANCES, LLC,featuring the company performers as well as Ballet West Academy students and dancers of Ballet West’s professional training division.

Silent Dancer, Salt Lake Acting Company. Photo: Joshua Black

Ruud picks the right sensations from his dance movement language to frame the movement vocabulary that dominates Silent Dancer. One of the most effective elements is the Jazz Age version of a Greek theater chorus with the four dancers in an ensemble, of which at least three have extensive modern dance training: McKenzie Barkdull, Makayla Cussen, Jorji Diaz and Savannah Roberts. The most incisive character moments of dancing include Michael’s half-male, half-female drag performance, which Richardson pulls off with spot-on pathos. Alice Ryan sashays exquisitely as Zelda, who, as many already know, came from a Montgomery, Alabama family of distinguished means but she always plunged into a self-made scandalous rebellion.

Cahill nails the tensions in the couple’s relationship. Ironically, in the actual details of her life, Zelda suffered a nervous breakdown in 1930 because she was frustrated about not becoming a ballet dancer. Kershisnik’s demeanor as the famous novelist mimics the writer’s true voice with credibility. Meanwhile, Archer brings a wonderful sleaziness in his dance moves as the bootlegger.

Silent Dancer, Salt Lake Acting Company. Photo: Joshua Black

While Rosie and Perry are polished in their dance partnering, they lack sensations of eroticism first and later guilt or fear that their relationship will be discovered and ridiculed by others. Both Reeve and Joe have extensive musical theater training but these moments lack the full emotional impact that comes with realizing the nuances of spatial relationship dimensions in how dancers move close and apart from one another. However, it is likely these elements will continue to sharpen and strengthen in subsequent performances, as the actors become more comfortable with the choreographic demands placed on them and their spatial relationships on stage. The production runs through May 12.

In general, Silent Dancer does a very good, albeit still imperfect, job at finding the nexus for dance and theater that breaks comfortably the formalities respectively in each performing arts genre. Many choreographers hesitate to use the term ‘dance theater’ in their bailiwick, arguing they know of no one in theater who would use the corresponding terminology of ‘theater dance.’ There can be fine differences in how choreographers adapt and respond to text, especially which may or may not be anchored or limited to one contextual interpretation.

However, it is evident that Ruud did relate properly to the text (both written and implied) that Cahill set in the script. He unlocked many possibilities of using dance movement language to amplify the text’s narrative impact. In many instances, the voices of writer and choreographer succeeded without either risking a lapse in tone or character.

The production’s visual design accentuates a Jazz Age tone effectively, thanks to Nancy Hills (costume designer), Dennis Hassan (set design), Joshua Roberts (projection design), and Michael Horejsi (lighting design).

Performances continue through May 12, daily Wednesdays through Saturdays at 7:30 p.m., and Sundays at 1 p.m. and 6 p.m. Additional performances include April 20, 2 p.m.; April 23, 7:30 p.m.; April 30, 7:30 p.m., and May 11, 2 p.m.

Ticket information is available at the SLAC web site.