For most of the 1980s, “officials in the state of Utah did nothing but sit back and watch people die of AIDS. That is not a hyperbole,” Ben Williams, one of Utah’s best known gay historians, wrote in a QSaltLake magazine several years back. Unfortunately, Utah was no exception at the time. Few people across the country believed a disease that initially was an automatic death sentence could affect them or their friends, families or professional colleagues.

Publicly, in Utah, the silence was deadly. As Williams recounts, a Wyoming attorney sued the State of Utah in 1984 because a mother died of AIDS, claiming that Utah officials failed to safeguard blood bank donations because they failed to tell gay individuals not to donate blood. Meanwhile, the state’s defense was that no gay community existed in Utah. As Williams explains, “The state lost its case when, as the archivist for the Utah Stonewall Center, I supplied the Wyoming law firm with information proving that, indeed, in 1984 there was a vibrant gay community in Utah.”

Only then did the larger Utah community and officials, with much recalcitrance, begin to pay the slightest attention to the AIDS epidemic. But, there was no Utah AIDS Foundation then; no resources on prevention or practices for safer sex. Williams said the only source was a toll-free AIDS information hotline published in a local gay periodical. In 1985, the Utah Department of Health reported 17 persons in Utah were living with AIDS. In 1990, it was the leading cause of death among young men in Salt Lake City.

In 1981, Dr. Kristen Ries, who was raised in a Quaker family among modest surroundings in Pennsylvania, arrived in Utah as an infectious disease specialist who originally was destined to work with geriatric patients. However, Ries and Maggie Snyder, who later joined the health care team, would handle virtually every AIDS patient case throughout the decade and beyond. As Williams wrote, “I am convinced that Providence sent the good doctor to Utah as the AIDS tide began to roll in.”

Their stories of compassion, humility and total dedication along with those of patients and families who were treated by Ries and Snyder are featured in Quiet Heroes, a new documentary which will premiere at Sundance 2018.

It is the quintessential Utah project in content and creative teamwork. Jenny Mackenzie, director, and Jared Ruga and Amanda Stoddard, co-directors, live and work in Utah. Mackenzie is an award-winning director of documentaries, which include Dying in Vein: The Opiate Generation, Sugar Babies and Kick Like A Girl. Torben Bernhard, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, served as director of photography. Bernhard, whose directing credits include the feature-length documentary The Sonosopher, is a Utah director who has won the Utah Short Film of the Year at the Utah Arts Festival three times within the last five years. Quiet Heroes, the debut feature-length released produced by Vavani Vérité (of which Ruga is president), also earned fiscal sponsorship from the Utah Film Center. Matt Mateus and Jeremy Chatelain of Spy Hop Productions produced the film’s score.

At the outset, Quiet Heroes presented significant creative questions that needed to be answered effectively if indeed the film was destined for a premiere at one of the world’s foremost independent film festivals. No doubt, as Ruga explains in an interview with The Utah Review, “it was a fantastic story” but would it be compelling enough to draw international audiences and a distinguished jury to the film’s attention. Ries and Synder, who were married a few years ago, are the epitome of humility, selflessness and understated tone. Likewise, many films, documentary and fiction, have captured superbly the AIDS crisis in its early years and the efforts to find preventive measures and treatment protocols that saved lives. One conceivably would wonder if anything knew could be said and portrayed in 2018.

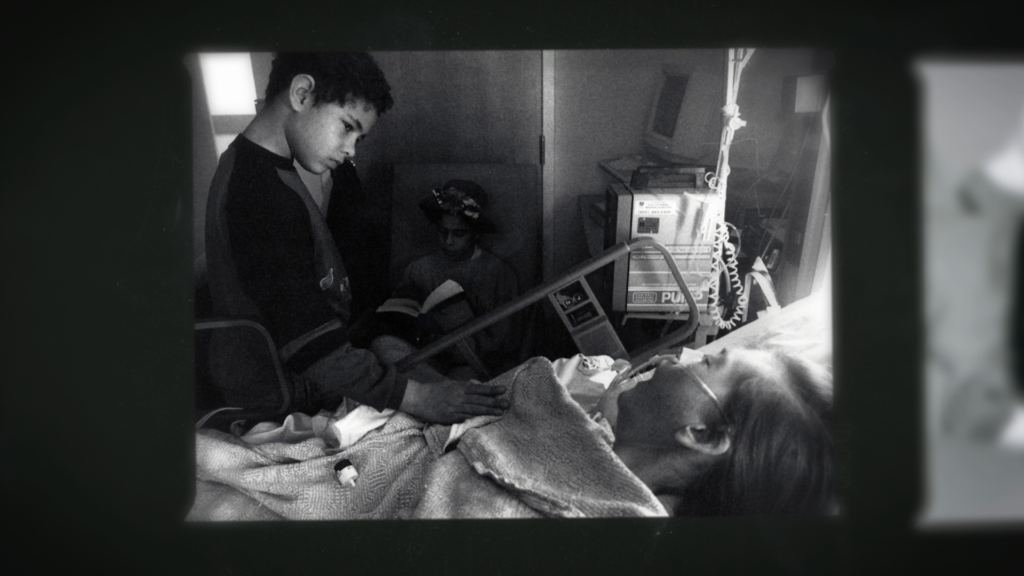

As Mackenzie explains, “while their story is remarkable, can I magically pull it out of them.” And, the film would need more than talking heads interviews. They would need the artifacts and voices of the patients and families whose lives were touched by the extraordinary compassionate care Ries and Snyder administered, especially when no other healthcare professional was willing to treat these patients.

As Ruga recalls, the production team’s first meeting with the couple convinced them of the thematic possibilities for a feature-length film. It was a classic afternoon tea, including crumpets, scones and other delicacies. “Maggie [Snyder] had arranged all these sweets and treats impeccably,” Mackenzie says, that “we instantly adored them.”

Working on the project, the creative team found ways of making the couple feel more comfortable with cameras in their lives. “Ries occasionally would wonder why we wanted to come back for more filming,” Mackenzie says, adding that one of the most pleasant experiences was accompanying them on a birding expedition, one of their favorite hobbies. “I didn’t realize that Utah was such a hot spot for birding,” she says.

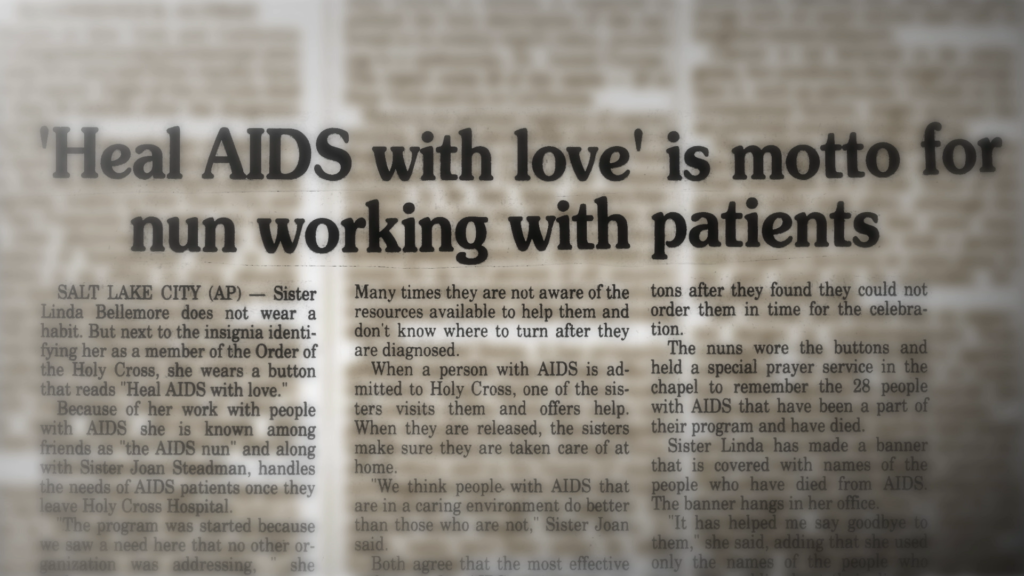

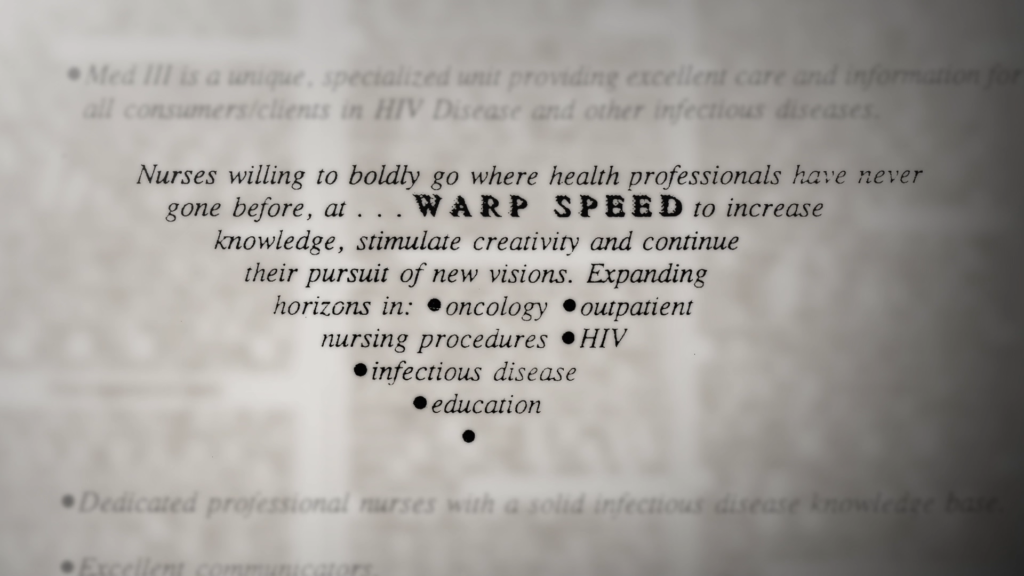

While Ries and Snyder could recall many details from events of more than three decades earlier, the creative team found that thanks largely to Snyder’s efforts, their life’s work, the stories and the legacies of the patients along with the progress and process about what was being done for the care and treatment of AIDS had been archived meticulously in scrapbooks and other formats. All of the archives are designated for the Marriott Library’s Special Collections program at The University of Utah. Thanks to the efforts of Ruga and Stoddard, photos, newspaper clippings and other artifacts have been treated and reproduced with outstanding results to be shown in the film.

One of the most prominent pieces in Ries’ home is a large oil painting by Utah artist Randall Lake. He had painted a series of works as an emotional response of losing so many friends and colleagues to AIDS. Lake had tried unsuccessfully to convince one of his friends who was suffering from the disease to pose for a painting. He eventually found someone who had been diagnosed with stomach cancer to pose for one of his works. Lake was a Mormon who had married and had five children. He always knew that he was gay but only came out after his lover committed suicide.

Among the interviews featured in Quiet Heroes are the key stories of three individuals who underscore the film’s overarching theme of compassion, conscience and conviction to sustain and be resilient even in the face of dire consequences. As dramatic as the stories seem, each leads to an uplifting epiphany and they collectively represent a spectrum of how the disease levied irreversible impacts on people’s lives, regardless of their social, ethnic, sexual identity and cultural backgrounds. AIDS was brutally nondiscriminatory.

One story is Kim Smith, the mother in a Mormon family, whose life seemed typical until her ninth wedding anniversary when her husband Steve revealed that he had sex with men. A few years later, Smith went for a routine medical exam and learned that she had contracted HIV and shortly thereafter, her husband’s health began to deteriorate, as he developed symptoms of AIDS. Despite the circumstances, Smith stayed with her husband, even as he tried to rationalize his previously hidden identity and the couple struggled to maintain their Mormon faith and connections in the family. The family’s story was captured in a documentary, directed and produced by Tasha Oldham, which aired on PBS’ (Public Broadcasting System) POV series in 2002.

“We were so fortunate, honored and humbled to be able to tell these stories,” Mackenzie says. “Smith’s story is so important in how it brings in family, faith and forgiveness.” The film includes family home video clips that have never been seen, which amplify the sincerity of unconditional love that sustained the family through its crises.

Another is Peter Christie, a survivor of the disease, whose career has spanned more than 30 years with Ballet West. Early in his career, he was a corps member and then a soloist but then he became increasingly unable to handle the physical demands as a dancer. He had increasing difficulty in lifting and carrying his ballet partner and only decided to seek medical treatment after his hairdresser broke down in tears when he discovered Christie’s hair was falling out so easily. “He had lost 40 pounds and it was remarkable that he could still perform at all,” Mackenzie recalls. Today, Christie is active as a dance educator, still affiliated with Ballet West’s academy programs. He also is on the faculty of The University of Utah’s School of Dance.

The third story brings in surviving family members of Cindy Stoddard Kidd, an activist who won a court battle with the state over the rights of people with AIDS to be married. Kidd had married her husband, Brian, at the age of 35, only to learn of the diagnosis two months later. She died at the age of 39 in January of 1996. Kidd was best known for publishing a monthly newsletter titled Positive Press, highlighting content for people with HIV or AIDS as well as those who wanted to support patients and individuals affected by the disease.

The Kidds’ case became prominent, as the couple were unaware of a law the Utah Legislature passed in 1987 that invalidated the marriage of any individual with AIDS. The husband had legally adopted Cindy’s twins and the couple wanted to ensure the marriage was valid in order for the adoption to be treated as such. The couple won the case in late 1993 when U.S. District Judge Aldon J. Anderson found the Utah law unconstitutional. When Kidd died, the Deseret News carried a surprisingly candid feature about the family members. Brian said, “”I think she was incredibly brave about the whole thing. . . . She spent most of her time trying to help other people that were also infected to try to make it easier on them to deal with it, and to try to make sure that even more people didn’t get infected.”

The simplicity of the film’s title Quiet Heroes conveys beautifully the testament of the work Ries, Snyder and the nuns of the former Holy Cross Hospital undertook. Mackenzie says the title did not come easily. Previous suggestions included ‘Ries and Snyder,” ‘Bloody and Unbound’ and ‘Doctors and Covenants.’ The final title came from a transcript by psychiatrist Paula Gibbs, according to Ruga.

The film is destined to become an important account of an aspect of Utah history that has never received its full merit. Ries certainly is one of the most important figures in the LGBTQ history of Utah. She was the first person to receive the Utah Pride’s community service award in 1987, which was established by Donny Eastepp, Emperor XII of the Royal Court of the Golden Spike Empire organization. The award since then has been named in her honor. She also was the first grand marshal of the Utah Pride parade.

However, the story of Ries and Snyder is not just one for the LGBTQ community. It is an integral part of the pioneer ethos that has made Utah’s history such a fascinating story. It is part of the Utah Enlightenment – a story that is part of a gradual but inevitable evolution of a mature, intelligent community that hopefully will never turn its back on anyone.

Days of 16-18 hours or more were common and sometimes the only thing Ries could do was just hold a patient’s hand. Ries and Snyder also had to deal with the ubiquitous enemies of urgent health – timely access to government health insurance benefits such as Medicaid and medications critical to keeping patients alive and from seeing their viral loads go into overdrive. They maintained an underground pharmacy and wasted no time in preparing paperwork.

For years often as the only defense in the front lines against a disease that wasted no time in taking victims, Ries and Snyder epitomized the greatest strengths of well-trained physicians and healthcare workers. Always vigilant about staying on point with the medical knowledge to fight the disease, they were even more attentive to the aspects that don’t always make it into the medical curriculum – to add compassion, love and respect for inclusiveness to the therapeutic protocol. And, today when many openly question whether public demonstrations of conscience against the most controversial injustices are worth the sacrifice, Quiet Heroes accentuates how the proper decision resonates with sharpness and profound meaning long after it has been made.

“This is what I like about their story,” Stoddard explains. “We truly felt honored to feature their work. And it hits at the right time when we definitely need a hopeful story.”

The quiet heroes were not just Ries and Snyder but also their patients, whose suffering and deaths would not become vain in the course of history. The immense progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS was made possible through the work of quiet heroes and the best way to honor the legacy is to ensure that not one person should ever have to endure the inhumane stigma which caused so many to suffer so much pain in silence. And, it is an example to reassure and give confidence to those individuals who will stand and act against any injustice, even if others hesitate or refuse to do so.

Screenings for Quiet Heroes are as follows:

Sunday, Jan. 21, 6:30 p.m. – Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, Salt Lake City

Tuesday, Jan. 23, noon – Egyptian Theatre, Park City

Wednesday, Jan. 24, noon — Holiday Village Cinema 2, Park City

Thursday, Jan. 25, 3 p.m. – Tower Theatre, Salt Lake City, community screening, free, public, seating limited

Friday, Jan. 26, 7 p.m. — Holiday Village Cinema 4, Park City

For more information about Sundance screenings and ticket information, see here.

Photos credit of Jenny Mackenzie, Jared Ruga and Amanda Stoddard.