In a scene in the middle of Mountain Meadows, a new play by Debora Threedy, Nita tells a Mormon elder, “We can’t put Mountain Meadows behind us if we won’t even admit it happened.” He replies that no one has denied its occurrence and that not talking about it might be the “best thing for everyone concerned.” Nita disagrees vehemently, after he says, “Nothing can change what happened. Let the dead rest in peace.” She replies, “It’s us who can’t rest in peace.” He responds, “Really, Sister Brooks, isn’t that a little overdramatic.”

Unwavering in her belief that the suppressed truth becomes its own lie, Nita says, “No, it’s the truth. I saw a dying man haunted by his memories. I’ve known sons ashamed of their fathers.”

Except for the date when Mormon pioneers entered the Salt Lake valley in 1847, the Mountain Meadows Massacre in September 1857 is the most well-known story in Utah history. But, it also is a story where extraordinary efforts continue to this day, quoting from an essay by Threedy, to “cover up and hide the trauma caused by the Massacre.”

Starting this Friday, Pygmalion Theatre Company premieres Mountain Meadows in a production directed by Morag Shepherd. It will continue through March 4 in the Black Box Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts in downtown Salt Lake City.

In 1950, when it was published, Juanita Brooks, a Utah teacher, wrote the most comprehensive book-length history about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ involvement in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. A decade after Mormons arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, a wagon train of 127 immigrants from Missouri and Arkansas were slaughtered in southern Utah by Mormon zealots. The only ones spared were small children. Only one man, John D. Lee, was ever tried for the crime. The jury did not reach a unanimous verdict in his first trial, but when he was retried he was convicted and executed. The story was that Lee had urged the Paiutes to join him in the massacre.

Six years ago, Threedy, a retired University of Utah law professor, began working earnestly on the play, conducting the historical research that has always been a hallmark in her works as a playwright. The story of Mountain Meadows was certainly not new to her. Sixteen years ago, on the 150th anniversary of the massacre, Threedy participated in a panel discussion with Shannon Novak, a forensics anthropologist who was alarmed by the manner in which remains of the massacre victims were cared for when they were excavated and exposed during the reconstruction of the gravesite monument in the 1990s. Novak’s book House of Mourning: A Biocultural History of the Mountain Meadows Massacre (University of Utah Press, 2008) traced the history of the group which was making the journey to California from the U.S. South, before their violent end in southern Utah. Threedy, who had taught and researched legal issues in archeology, was asked at the panel discussion about who might have legal claims to the remains or any property that might have been uncovered, when they were accidentally exhumed in the late 1990s. “The best answer I could give at the time was no one,” she says, in an interview with The Utah Review. To this day, as noted later in this preview, there are still significant questions to be conclusively answered.

The play is a braid (as Threedy explains), weaving two stories and alternating back and forth through timelines in the 19th and 20th centuries. The story of Miranda, covering barely a decade at most, leads to startling discoveries. She was one of the young survivors of the massacre and she is committed to finding the details of her family’s involvement in the killings. Covering thirty years, the other narrative braid is about Nita (the historian Brooks), who is the granddaughter of one of the perpetrators of the massacre, and her groundbreaking historiographical efforts to unearth the truth behind Mountain Meadows.

Brooks’ book about Mountain Meadows remains vital and relevant. John Baucom of the Association for Mormon Letters described it as “an unimpeachable classic within Mormon history.” Craig Smith, who edited the 2019 book The Selected Letters of Juanita Brooks, which was published by The University of Utah Press, wrote that her work “served as a bridge to the new, more progressive era” in Mormon historiography.

The words of Brooks anchor the themes of the narrative braids in the play. For example, in the edited volume of her correspondence, regarding a letter to Jesse Udall, a descendant of Lee (the only person executed for the crime) who served on the Arizona Supreme Court, Brooks wrote, “I believed then, as I believe now that nothing but the truth is good enough for the Church to which I belong, and that God does not expect us to lie in His name.”

In the interview, Threedy talks about the path that led her to writing the play. When she retired from the university seven years ago, she moved to Dammeron Valley, a small community approximately 15 miles northwest of St. George. She soon discovered just how close she was to the site. In a brief essay titled Hidden Trauma on the Ground, she describes what she learned during her frequent commutes from her home to Cedar City, on the I-15 highway:

The route now followed by I-15 south of Cedar City crosses an ancient lava flow called Black Ridge and then drops precipitously down to Ash Creek. In 1857 this route was passable by riders on horseback but was all but impassable to wagons. In some sections, wagons had to be lowered down with ropes. By September 1857, only a handful of wagons had made the journey over this route and all of them suffered damage from the rough road.

After the September 1857 massacre in Mountain Meadows, the bodies were hastily buried in shallow graves and were almost immediately dug up by scavengers. The first wagon train that came down the California Trail about a week after the massacre was forced by the local settlers to go through Mountain Meadows at night, so they couldn’t see the scattered remains. Those remains would not be buried until 1859 when the U.S. Army investigated the massacre and collected the remains into several mass graves. The second train that came through after the massacre was directed to follow the Black Ridge route; allegedly, the smell of the decomposing remains was so horrific that even passing in the night would not have hidden what happened there. After that, it was winter and travel over the Trail basically halted until spring. The rudimentary roadway over Black Ridge was then improved so that wagons would have an easier time of it, and the next year travelers were advised to use the new route to avoid the “danger” posed by Native Americans along the old route.

The frightening urgency of the Mormon community’s unconditional resolve to suppress evidence of the mass execution is conveyed in the words of the characters Threedy has formed in the play.

Threedy says, “Originally, I wanted to have three strands of hair for the braid.” She had set out to write each story separately and then decide how to braid them. The two that are in the play came together quickly. The third proved to be too complex to fit within the narrative braid. In 1999, Gordon Hinckley, then church president, spoke at the dedication of the new gravesite memorial. He said, “That which we have done here must never be construed as an acknowledgment of the part of the church of any complicity in the occurrences of that fateful day.” In 2002, Will Bagley’s book Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (University of Oklahoma Press) brought perhaps the church leadership’s strongest response, when Bagley put forth the argument that then church president Brigham Young ordered the massacre. But, historians also have cautioned others not to make the claim, as there is not sufficient verified evidence to fully substantiate it. Nevertheless, the book makes the case that Young, church officials and leaders in southern Utah did systematically obstruct procedures of justice related to the massacre. Also, Everett Bassett, a historical archeologist, continues to study evidence concerning a ranch close to the Mountain Meadows massacre site (then owned by Jacob Hamlin) where the 17 surviving children were taken after their families were killed.

But, the lead-up to the day of that 1999 rededication also had threatened to expose and risk a collapse of the church’s long-standing campaign to permanently suppress the starkest evidence of the massacre. “The church had tried so hard not to disturb the grave but when they tore down a wall, human remains were uncovered,” Threedy says. She explains that whenever an anthropologist or archeologist uncovers human remains, they are obligated to notify law enforcement authorities (for example, the county sheriff) to investigate any possible crimes that might rise to prosecutorial standards. In those instances where prosecution is not determined or claimed, then the remains are to be sent to the state archeologist for investigation.

Some 2,000 bone fragments were gathered and transported to Salt Lake City. Threedy recalls that Novak, internationally known for her forensics expertise in war crimes investigations arising from the Balkan Wars, was outraged that Utah had given into pressure (certainly under the presence of church leaders) not to continue or expand scientific investigations of the remains.

“For this play, I tried to make this story fit but I just could not find it,” Threedy says, adding that she continues to think about how she might realize this third strand as part of a theatrical narrative. Like Brooks, Threedy has experienced the enormous amount of perseverance and conscientious methodological considerations that Brooks found in the process of revealing the truth behind the massacre.

For Pygmalion Theatre Company, Mountain Meadows is following on the heels of a smashingly good world premiere of Julie Jensen’s Mother, Mother: The Many Mothers of Maude last November. In 2019, the company offered a new production of Two-Headed, a fictional play by Jensen which premiered nearly a quarter of a century ago. Featuring two Mormon women, that play opens on the day in 1857 when the Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred, at which the characters were just 10 years old.

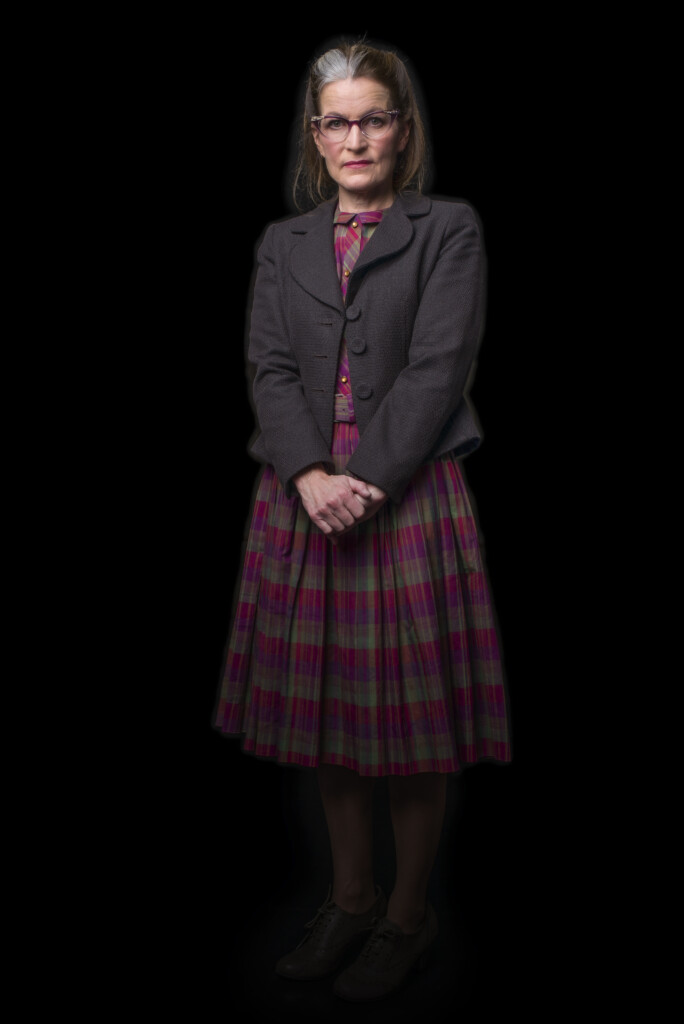

The Mountain Meadows production includes two outstanding Utah playwrights well known to theatrical audiences: Shepherd as director and Matthew Ivan Bennett who plays three characters. The cast also includes Stephanie Howell, David Hanson, Carlie Young, Tiffani DiGregorio and Daisy Blake.

Performances will be on Thursdays and Fridays at 7:30 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m. For tickets and more information, see the Pygmalion Theatre Company website.