Seven years ago, when Peter Bromberg was named the new associate director at the Princeton, New Jersey public libraries, he was finishing renovations on his home, a project lasting 18 months. In a Library Garden blog post, he wrote about the customer service turnaround at Home Depot, a store he visited frequently:

The most noticeable (and appreciated) phenomena though is how Home Depot has handled some recent problems with a damaged sink, and the return of a few (expensive) items that we did not need. On three different occasions, three different customer service agents took care of me, ensuring that the returns were taken, restocking fees were waived, and the stockroom was manually checked for a replacement part even though the computer said it wasn’t in stock (and the correct item was found saving me a trip to another store.)

Bromberg appreciated the store’s employees for being on his side as agents, not as unflinching gatekeepers of store policy. They were patient, reassuring and sincere in resolving his problems. He had worked on the other side of retail – two stints as a Nordstrom sales associate in Spokane, Washington, where he received perfect customer service scores in ‘secret shopper’ telephone transactions.

Bromberg’s job in Princeton’s libraries marked his return to public service after working in a New Jersey regional cooperative that provides professional development and networking for hundreds of libraries. “I will strive to keep this experience, and the ideas of hospitality and agency – of being on the side of my customers (both internal and external) – uppermost in my mind,” he wrote in 2010. “Being on the side of the customer is a simple idea, but one that offers powerful guidance. And, I hope, powerful results.”

As Bromberg settles into his role as executive director of Salt Lake City’s public library system, the aspects of hospitality and agency already are rejuvenating the community-centric ambience of the cathedral-like urban living room in the main branch.

The organizational culture is just as personable in the system’s seven branches. There are many small changes and new touches, some of which already were being implemented by his predecessor, John Spears, who is now executive director of the Pikes Peak Library District in Colorado.

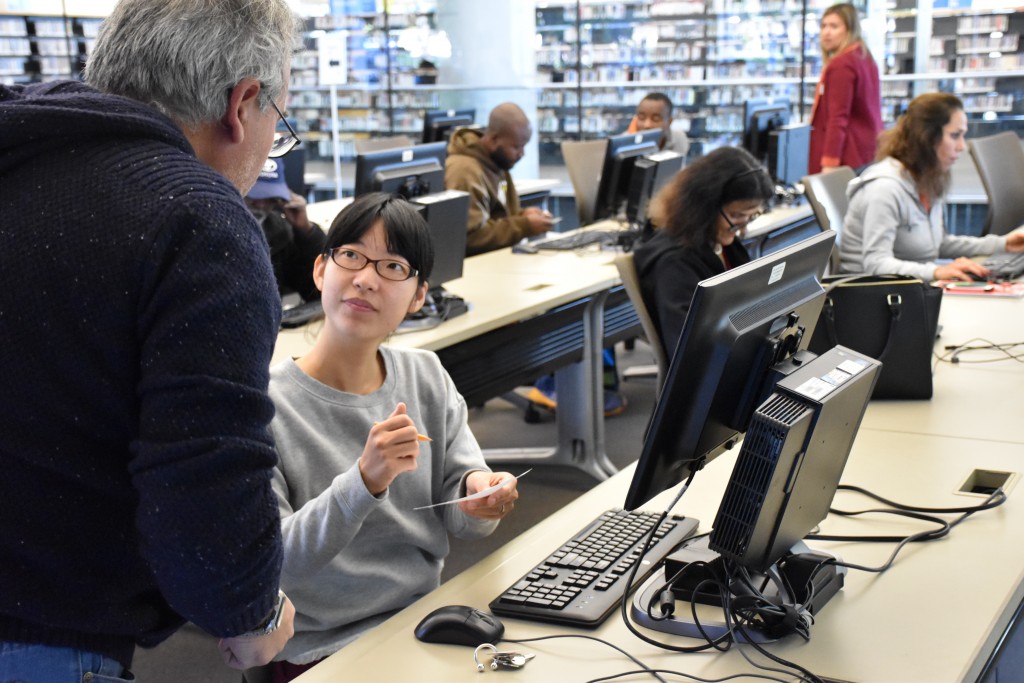

Staff members greet patrons and direct them to the right desk or individual for their particular needs and questions. Computer and digital tech lab employees are especially patient in helping patrons who struggle with digital literacy. Volunteers of America’s library engagement team also are visible to help members of the homeless community.

Before the recent wave of snowy, unusually cold weather hit the city, crews were refurbishing the library’s grounds, which will be impressive once spring sun and temperatures arrive. The main library’s campus of 240,000 square feet, which will be 15 years old in 2018, is getting new carpeting and an overall freshening.

Likewise, Bromberg wants to make sure the five oldest branches get as much attention as the system’s two newest locations – Marmalade at the city’s northern gateway and Glendale on the city’s west side where more than one-third of the population is Hispanic and a strong influx of refugees means that more than 80 languages are represented in the area surrounding the branch. The library’s staff is cosmopolitan: a solid one-fifth of the library’s workforce is fluent in other languages. At least 25 languages are represented.

Ray Oldenburg, in his 1989 book The Great Good Place, wrote that healthy citizenry occurs in a balance of experiences situated in home life, workplace life and socially inclusive spaces. Bromberg says in an interview with The Utah Review, “Libraries are well positioned to be that third place and libraries always have done it well.”

SLC’s main branch alone provides sufficient proof of community engagement. Last year, 1,837 bookings, programs and events were held in the downtown location and 78 percent were slated for community, individual, educational and nonprofit use. This includes the annual Utah Arts Festival which draws more than 80,000 visitors every year in late June.

And, library staff members have created programming that brings many alternative forms of creative expression to the public. 12 Minutes Max, which presents films, readings, and other art forms once a month on a Sunday afternoon, is attracting a steadily growing audience.

Last year’s Salt Lake City Performance Art Festival, coordinated by librarian Kristina Lenzi, featured a dozen artists from Utah and elsewhere. It drew more than 5,000 attendees over two days. Bromberg says other library staff are being encouraged to propose new programming ideas, which might be funded by small grants through the system’s budget.

However, if libraries are to be strengthened as the third great good place in their communities, Bromberg also sees the major shifts in the information and technological landscapes of the last 25 years as critical to libraries getting their mission right. In his own blog Curious Kind, he wrote about what a library’s mission might be in 2017: “I’d offer that the mission of libraries is not books (which is a format, a form) or even information, but learning, self-directed exploration and growth, early literacy, stimulation of imagination and curiosity, strengthening of community and civic connections, job readiness and economic development.”

While library staff members might decide to focus only on a handful of goals, the values of learning enhanced by the connections created in the community should drive these decisions. When Bromberg wrote his blog post in 2015, he was commenting about a library’s role in the blossoming makerspace movement. The decision should not be constrained by the library’s scarce resources or tight budgets, he explains, but it also should acknowledge trends and things that perhaps members of the community have not yet anticipated or imagined.

“It is our responsibility to add value to their lives by anticipating things we could be doing, aligned with our mission, that will surprise and delight them,” he wrote, “Our job is to help shift their perceptions and expectations about what a library is or could be in their lives, and in the lives of their family and community.”

Paying attention to core values has rehabilitated the library’s public profile, particularly after the leadership crisis that nearly decimated the institution’s trust bank with the community five years ago amidst the three-year chaotic, controversial tenure of Beth Elder. Bromberg, who most recently was associate director for public services in the Salt Lake County’s public library system covering 18 branches, is the latest steward in the renaissance which was adeptly supervised first by interim director Linda Hamilton and then Spears, who came to SLC after a successful tenure in two Illinois library systems.

Bromberg is an ideal match for the state’s largest library system: Salt Lake City has the highest per capita square footage dedicated to public library services of any American city. And, his connections to Utah are even more extensive than his professional record indicates.

While he spent 30 months in the Salt Lake County library system, he has connected with many of the leading figures in Utah’s library communities through numerous organizations and conferences throughout his professional life as a librarian, executive coach and as a nonprofit leader. For example, in 2002, the Rutgers University graduate attended the Snowbird Leadership Institute with Nancy Tessman, former SLC library director who led the system’s move to its current downtown location.

Bromberg is widely sought as a presenter, coach and facilitator in many settings. He contributed the concluding chapter in a 2016 book, Crucible Moments: Inspiring Library Leadership (Mission Bell Media). He wrote about the efforts to save New Jersey’s 24/7 collaborative virtual reference service that he helped to create while he was assistant director at the South Jersey Regional Library Cooperative. State officials abruptly ended the service, which was the first of its kind in the U.S., and some colleagues wondered if they should press the cause of saving it amidst a politically divisive climate. Meanwhile, Bromberg and others saw grass-roots organizing as the best platform for resurrecting the service in a new form.

He also serves on the board of directors for EveryLibrary, a nonpartisan, nonprofit, social welfare organization chartered to work on local library ballot initiatives. The group coordinates grassroots activities to support local library ballot measures, trains library staff and leadership on effective “information only” campaigns, and helps libraries prepare for state legislative matters. These skills are acutely needed both at the local and state levels in Utah. For instance, budgetary resources have not increased in line with the expanded physical capacities of the public library system.

Bromberg sees numerous potential ‘crucible moments’ for cultivating leadership among the library staff – as he frequently describes in his writing and presentations, learning to leverage influence that mobilizes people to act for the interests of a cause and goal. SLC’s libraries already offer numerous examples of the diversified mission goals he mentioned earlier. For example, one out of every six items checked out by library patrons last October was a digital item in the library’s collection.

Children and teen services at the main library as well as the neighborhood branches engender benefits especially for lower-income families that go beyond providing resources to finish homework or prepare a science fair project. For example, at the Chapman branch, there are dance, science and art programs and kids can volunteer to work at the annual Christmas thrift store where kids redeem points they earned for reading books in exchange for gifts, puzzles and toys. Librarians are at the forefront of educational initiatives, taking library programs to area Title I schools, Head Start classes, the YWCA, and Odyssey House.

Established 20 years ago, the library’s collection of zines and alternative press publications – the first of its kind in an U.S. public library — includes many locally produced items among its 3,000 titles. This sets an appropriate platform for expanding the library’s local collections, including music produced by area artists along with books and self-published materials. Utah has several publishers that have expansive catalogs covering a wide spectrum of literary genres including Torrey House Press and Gibbs Smith. “This goes directly to making everything more accessible to the community,” Bromberg adds.

A month before the 2016 presidential elections, the Marmalade branch hosted a political buffet, coordinated with KRCL’s RadioActive, that included representatives from all five political parties on the state’s ballot as well as voter registration groups. “The library is at its best as a civic space,” Bromberg explains, adding that it always should be a “safe, neutral space.”

Initiatives such as the Tech League underscore the large requirement for libraries to mitigate and eliminate the problems of the digital divide and to honor their historical mission as providing access to information and knowledge. The challenge, as it was in trying to continue New Jersey’s virtual reference service, is embedded in the scarcity issue. “We’ll find partners and pool our resources,” Bromberg says, adding that the Friends of the Library has proven particularly vital in its long history of support.

However, Bromberg advises that it is not sufficient to be responsive but to contemplate what is possible beyond the contemporary imagination. The important aspects of equal access and literacy became most visible in the 1960s when President Kennedy’s administration drew the connections between reducing poverty and emphasizing adult literacy. The customer’s request might not be the best indicator of the most valued or patronized services. “In my nine years of programming continuing education classes for a multitype library cooperative, the most popular classes — the ones where registration filled within the first hour — were consistently the ones that no one asked for; classes on topics such as Twitter, social bookmarking, blogging, effective presentations, etc.,” Bromberg wrote in his blog. “People asked for advanced excel classes, book repair, Reader’s Advisory, and these classes would get low to middling turnout.”

Fortunately, SLC’s libraries are wisely positioned to be as flexible and agile as Bromberg envisions when it comes to finding new avenues for engagement, lifelong learning, and being as relevant to the community’s ever-changing needs. Coding clubs and activities that are geared toward traditionally underrepresented groups or those who have limited digital access at home or at school are an example. Likewise, the creative boundaries of plugging artistic and aesthetic elements into STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) topics are stretching at a rapid pace with the increasing presence of 3-D printers and affordable virtual reality tools. There is a growing interest in learning to make films, remixing music and using electronic tools to create multimedia works.

Bromberg, a suitably visible director for the library system, is ideally poised to be among the most important educational and cultural ambassadors for Salt Lake City, as demographic shifts, technological advancements and a burgeoning creative arts and letters movement are remaking dramatically the community’s profile.

1 thought on “Peter Bromberg is Salt Lake City Public Library’s newest steward, ambassador for learning, cultural engagement”