EDITOR’S NOTE: All photos are credited to Sharon Kain.

Before recounting the overflowing cornucopia of kinetic performances that embodied Repertory Dance Theatre’s (RDT) most recent concert Sounds Familiar, it is worth considering the aesthetic epiphany that emerged from asking a dozen choreographers to set a work of their own interpretation to some of the most familiar classical music of the Western canon.

Take, for example, choreographer Luc Vanier’s extraordinary setting of the famous second movement (Allegretto) from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92. We sometimes forget that what really made Beethoven’s music so memorable was rhythm rather than melody.

As Hector Berlioz (a 19th century composer) famously described, the rhythmic pattern in this movement is a “dactyl [one long and two short syllables] followed by a spondee [two long syllables] played relentlessly.”

Under that rhythmic pattern, the melodic line alternates between anguished, resigned expression and a glimmer of sublime, gentle hope, a brief but poignant throb of nostalgia.

More than 200 years after this music was composed, Vanier translated this to a familiar existential fear of our time, as dancers Lauren Curley and Dan Higgins appear in a post-apocalyptic tableau – survivors of catastrophic destruction, the sort that we fear will occur more frequently in a volatile climate crisis.

Both dancers, clad in government-issued plastic coats that victims of a flood, tornado or hurricane might wear, simulate the movements of survivors trying to cope with the aftermath.

One stage prop is an old television set from which we hear Beethoven’s music. The recording has been doctored to produce a scratching noise that almost but not quite overwhelms that hopeful yet fragile, translucent melodic line from Beethoven. The backdrop comprises video images, representing the artifacts of a shattered routine of life that suddenly have lost their purpose. We see agricultural sprinklers continue to spin in a field, for example, presumably with no crops to tend. Vanier collaborated with Kym McDaniel to produce the video content.

Amidst these elements, the dancers rendered Vanier’s translation of this fabulous music with utmost conviction.

Every scintillating moment of this concert demonstrated just how dance boosts the stimulus of the music’s melodic and rhythmic dynamics. The symbiotic effect of each choreographer’s translation of a specific classical music warhorse and the company’s stellar performances made both the art of music and the art of dance more accessible, legible and elucidating for audiences.

Three of the choreographers deftly handled the challenges of Bach’s music. Marilyn Berrett’s setting of the first movement of the Brandenburg Concerto No.3 in G Major, BWV 1048, for the RDT company translated the galloping sensation of the ritornello with spot-on results.

The music is scored for combinations of violins, violas and cellos in threes. And the dancers produced a damn precise corollary of the music’s textures, as the small combos of dancers often were pitted against each other and periodically came together in unison.

Molly Heller produced three solos, each presented separately at various points in the concert, based on the opening prelude of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007.

The first two soloists (Daniel Do and Jaclyn Brown) beautifully captured the foremost dilemma of playing anything by Bach. Purists demand unwavering allegiance to technical accuracy of interpretation while others believe that one should not deplete such great music from its emotional core.

Do and Brown evoked these tensions in compelling ways. Finally, in the third solo, Jon Kim achieved the wondrous balance between technique and emotional affect of Bach’s music that continues to captivate our 21st century experience.

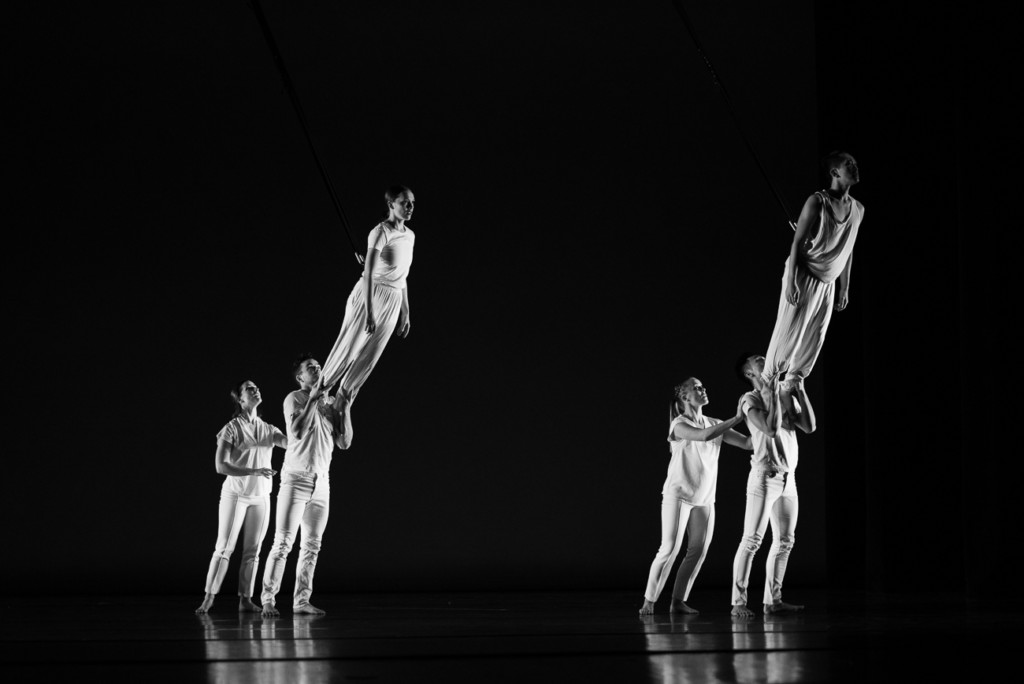

Nancy Carter, the 2019 winner of RDT’s Regalia choreographers’ competition and part of the Aerial Arts of Utah, did a gobsmackingly good take on one of Bach’s masterpieces for organ, Fugue in G minor, BWV 578 (also known as the Little Fugue).

She stitched four musical interpretive snippets together – from the original score for organ, the Swingles’ a cappella performance, a metal rock version and the sweeping Stokowski orchestral arrangement.

Two of the dancers (Elle Johansen and Kim) were strapped into the bungee cords, intermingled among the four other dancers (Brown, Curley, Higgins and Do). It became a thrilling translation of Bach’s counterpoint with a glorious climax, just as the music escapes the minor key and ends on a triumphant G major chord.

Along with Vanier, two other choreographers tackled Beethoven selections with equally impressive effect. Natosha Washington astutely stripped out the conventional romanticizing feel of the famous opening movement of the Moonlight Sonata (C-sharp Minor, Opus 27, No. 2). With the music performed live by pianist Ricklen Nobis, the dancers (Ursula Perry and Tyler Orcutt) magnificently harkened back to Beethoven’s intention of the work as a fantasy.

The piece was dedicated to a young woman who studied with Beethoven but it really has much darker tones than what has historically been associated with it. Beethoven’s personal life, at this time, was turbulent for numerous reasons (his deafness and the acknowledgment that his love for others would never be reciprocated).

Nicholas Cendese, RDT artistic associate and development director, astutely flipped the clichés of Beethoven’s most famous bagatelle: Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor for solo piano, commonly known as Für Elise. There have been at least three accounts about who Elise was and none has ever been decided. Do and Kim had the delightful, witty honors with Cendese’s clever translation, adding just the right bit of sass in their nonverbal gestures and eye contact.

The other selections were just as ingenious. Stephen Koester’s darkly humorous take on the foreboding Waltz from Aram Khachaturian’s Masquerade matched well with the music’s original and tragic intentions. In Khachaturian’s version, a woman is fatally poisoned by her furious husband who suspects her infidelity, an allegation that turns out to be false.

Most of the dramatic action takes place at a masquerade ball. Koester sets Orcutt as the hapless victim, in a no-holds-barred version of a well-known televised dance competition, complete with color commentary (Curley and Do) and the other dancers joining in on the aggression (Perry and Higgins).

Opera also engendered some truly elegant moments, as in Sharee Lane’s translation of the aria O Mio Babbino Caro from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. Perry’s solo elucidated the innocent appeal associated with the main character’s daughter, ending on a radiant note, precisely matching every line in one of opera’s most familiarly gorgeous arias.

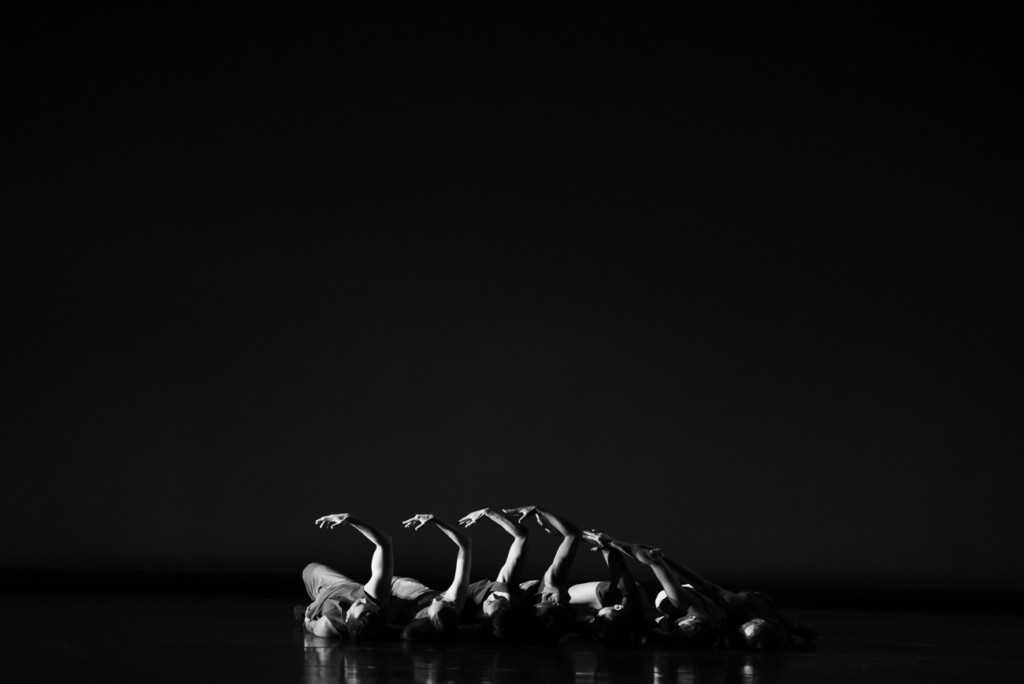

Likewise, Nathan Shaw did eminent justice in his choreographic translation of Puccini’s Nessun Dorma from the composer’s last opera Turandot. Working with perhaps the most famous recording of the aria by the late Luciano Pavarotti, Shaw gave the dancers (Brown, Curley, Higgins, Johansen, Do and Kim) the “money steps” to go along with Pavarotti’s most memorable “money notes.”

Sara Pickett translated the ebullient playfulness of the closing Rondo of Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto into an absolutely charming showcase of the company’s tightly-knit ensemble character. Susan Hadley gave Brown and Do a quick-paced good-natured brawl, accompanied by the Bransles dance in Peter Warlock’s Capriol Suite.

Meanwhile, Brown and Johansen, like their peers, distinguished themselves in eye contact and gestures, as they crept and leaped to Higgins’ wry and sly rendering of In the Hall of the Mountain King from Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite.

Finally, John Mead put the sparkling cap on an immensely satisfying concert in his excellent translation of the closing molto vivace movement of Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony 1 in D Major (also known as the Classical).

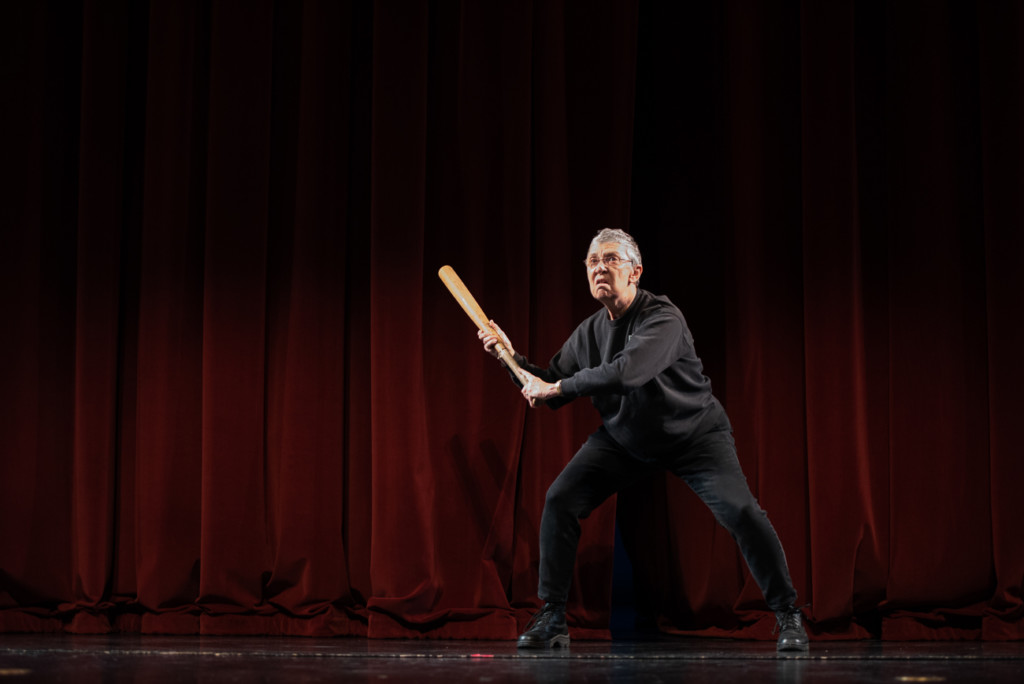

From the brief opener with Linda C. Smith, RDT’s executive and artistic director, taking a fly swatter and then a baseball bat with the rapid buzz of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee, the concert tore through the evening in a generous exhibition of choreographic pleasures to whet the holiday spirit. This would be a great touring show for building dance and music appreciation in the schools.

RDT’s next concert will be Emerge (Jan. 3-4), featuring original choreography by seven company dancers.