At one point in Good Standing, certainly among the top three original plays ever produced by Plan-B Theatre, Curt (played by Austin Archer), facing the 15 men who will decide if he should be excommunicated from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints because he married a man, tells us there are no secrets in a Mormon congregation even if its members have been reminded repeatedly of the evils of gossip mongering.

Curt says it “really pokes holes in the, uh…requisite self-righteousness you need in moments like these.” Pointing to the empty chairs, he rattles off the litany of his “jury’s” own failings. One had an extramarital affair. Another has a daughter arguing for women’s ordination on social media. “And this one still hasn’t lived down the fact that he saw Saving Private Ryan during the church’s R-rated movie prohibition. But this one, he should sympathize. Skeletons in his closet… Maybe I’m the furthest thing from his mind.”

In that impressively timeless essay On Morality that Joan Didion wrote in 1965, which later was published in the Slouching Toward Bethlehem collection, she explained that when it comes to any and all questions, “they are all assigned these factitious moral burdens. There is something facile going on, some self-indulgence at work.” She continued, “Because when we start deceiving ourselves into thinking not that we want something or need something, not that it is a pragmatic necessity for us to have it, but that it is a moral imperative that we have it, then is when we join the fashionable madmen, and then is when the thin whine of hysteria is heard in the land, and then is when we are in bad trouble. And I suspect we are already there.”

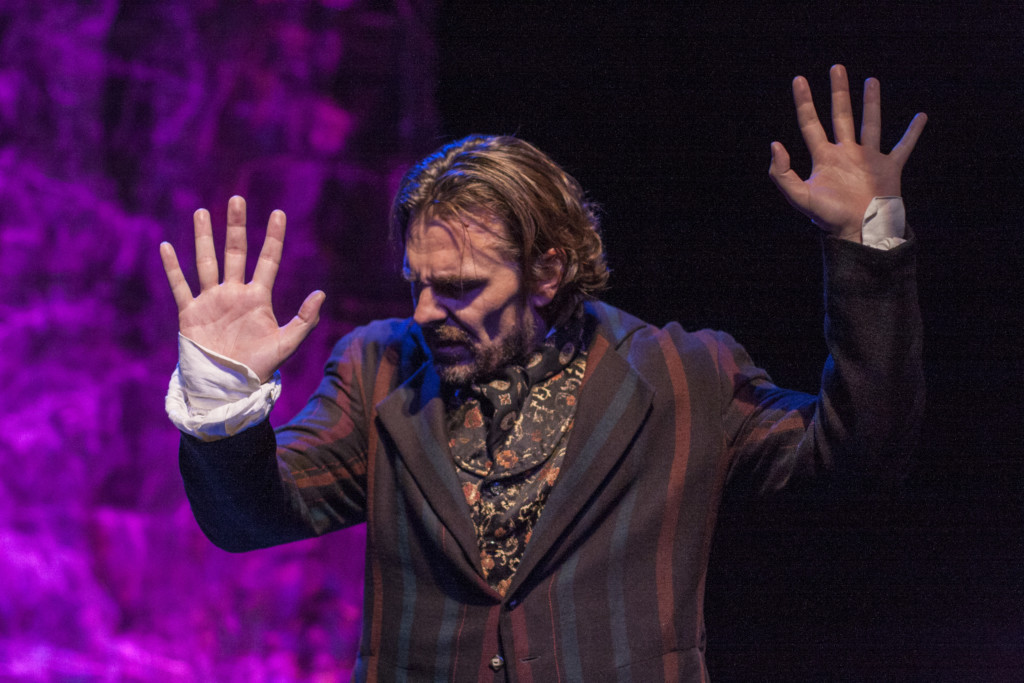

In Good Standing, playwright Matthew Greene achieves a singular incisiveness about the church to which he once belonged and to his own lifelong contemplation about self-respect and conscience. Archer, who takes on 16 roles including the young man being excommunicated along with the members of the Mormon church’s high council and stake presidency, astounds in how he shifts with one or two movements, tone or gestures from one character to another – just enough to make it thoroughly clear to the audience. There are subtle changes in dialect that any Utahn would recognize or the way he sits in a chair or folds his arms when standing, as he becomes another character. Archer delivers a full spectrum of emotions — witty and humorous to rueful and arrogant and to bittersweet and heartbreaking.

The production, which unquestionably will sell out the house for its five remaining performances from Thursday, Oct. 25, to Sunday, Oct. 28, also will travel to New York City at the United Solo Festival for a Nov. 4 performance (see below for a sidebar feature). As usual, the play features the delicate director’s hand of Jerry Rapier.

Good Standing will be a masterpiece in the canon of creative works that comprise the Utah Enlightenment. As The Utah Review has previously described, “Plainly, the artistic and creative works placed under the aegis of the Utah Enlightenment do more than the purpose of ‘art for art’s sake.’ They elevate the contemporary experience – with the sum of its tensions, problems, conflicts, disappointments and crises – to an enthralling sensation of healing and empowerment.”

In finding the appropriate context for judging the holistic experience of this production, it is worth considering one of the series of literary conversations James Baldwin had with colleagues. Nearly 40 years ago, Baldwin sat with Chinua Achebe of Nigeria, the legendary figure of the African literary movement, to talk about aesthetics and morality. In explaining that writers are not receivers but makers of aesthetics, Achebe said, “Aesthetic cannot be fixed, immutable. It has to change as the occasion demands because in our understanding, art is made by man for man, and, therefore, according to the needs of man, his qualities of excellence.” Baldwin responds that the word ‘morality’ sleeps beneath aesthetics, adding that “and beneath that word we are confronted with the way we treat each other. That is the key to any morality.”

This is the heart of Greene’s play, which translates the uniquely Mormon experience into a meditation that speaks just as compellingly to non-Mormons, as we wade through the disturbing and dangerous agitprop only to discover how cruelty, indeed, has become the point of it all.

By the end of the play, a conclusion that reverberates long after everyone has left the theatrical house, one realizes just how much has been dismantled with laser-like precision in Good Standing. Again, it is worth reaching back for context. Forty years ago in a devotional talk titled All Are Alike under God at Brigham Young University, Mormon apostle Bruce McConkie spoke after the “revelation” that ended the ban on black members from joining the Mormon church’s priesthood. McConkie spoke about the insufficiency of language in articulating what had transpired. He said, “To carnal people who do not understand the operating of the Holy Spirit of God upon the souls of man, this may sound like gibberish or jargon or uncertainty or ambiguity; but to those who are enlightened by the power of the Spirit and who have themselves felt its power, it will have a ring of veracity and truth, and they will know of its verity. I cannot describe in words what happened; I can only say that it happened and that it can be known and understood only by the feeling that can come into the heart of man.”

At one point in the play, Archer assumes the role of President Spade, one of the men who will decide Curt’s fate. Spade recounts his own experiences with “temptations,” his struggles with being “broken,” and how his life had been transformed when he met his wife. He regrets not having talked to Curt, despite the fact that he had known him since his boyhood days. “We don’t tell these stories. We don’t tell these young men, boys like Curt…or like me. We don’t tell them there’s hope. Maybe it won’t be quite what they imagined and maybe no one writes songs about it. Maybe they still wonder sometimes what life would be like if they could just…burn like they used to. And they might look at an engagement photo with two tuxedos one day and just think…wow.” Spade ends his remarks on the differences between ephemeral happiness and eternal joy, which happens when “you’ve been righteous, when you’ve done all you can.” But, even Spade is not convinced of these words.

Returning briefly to Didion, she wrote her short essay in the middle of Death Valley on a hot July night. She had been talking to a local nurse about an automobile accident in which the driver was killed instantly but his passenger survived. Her husband, a miner, stayed with the corpse on the side of the desert highway until the coroner arrived because otherwise the coyotes would have eaten its flesh. The nurse said it would have been immoral to abandon the body. Didion says that in this specific instance, she did not “mistrust” the nurse’s use of the word. Didion wrote, “one of the promises we make to one another is that we will try to retrieve our casualties, try not to abandon our dead to the coyotes. If we have been taught to keep our promises – if, in the simplest terms, our upbringing is good enough – we stay with the body, or have bad dreams.”

In Good Standing, the men convened to decide Curt’s fate are paralyzed by the hold of an untruthful morality couched in the most primitive form of survival, not in the attainment of a truly personal sense of spiritual good. Indeed, to borrow a phrase from Didion, there is a most sinister yet silent hysterical fear that runs through the minds of the 15 men who have been commanded to carry out an extraordinarily difficult duty.

The production team includes Keven Myhre, set design; Matt Taylor, lighting design, stage managers Catherine Heiner and Jennifer Freed, rehearsals and production, respectively. It is as austere a production could be in terms of props or music. It is a stunning, unfiltered evocation of the power of language and commanding presence of a solo performance.

Tickets are selling quickly. Performances continue this week on Thursday, Friday and Saturday at 8 p.m., and matinees on Saturday at 4 p.m., and Sunday at 2 p.m. More information is available at the Plan-B Theatre website, which updates ticket availability continuously.

UNITED SOLO FESTIVAL

The United Solo Festival is the world’s largest gathering of solo theatrical works, held annually in New York City. This year’s festival, which began Sept. 13 and continues through Nov. 18, features more than 100 works from around the world and are staged at Theatre Row (410 West 42nd Street) in New York City.

Good Standing (Nov. 4, 2 p.m.) will be the third Plan-B Theatre original production in the last five years to be staged at United Solo.

In 2013, Matthew Ivan Bennett’s Eric(a) was presented. Plan-B’s first commissioned play for a solo actor (Teresa Sanderson), Eric(a) is about a trans* man in his fifties who falls in love with a woman for the first time. The play took Best Drama honors at the festival.

Two years later, it was Eric Samuelsen’s very loose adaptation of The Kreutzer Sonata, the Leo Tolstoy novella, as a one-man show with actor Robert Scott Smith. The Salt Lake City premiere featured excerpts from Beethoven’s famous violin sonata of the same name, performed live by Kathryn Eberle, violinist, and Jason Hardink, pianist. The music was recorded for the play’s United Solo performance that year.

Another solo show from Salt Lake City, Do You Want to See Me Naked?, written by Morag Shepherd of Sackerson Theatre and performed by Elizabeth Golden, will be performed Nov. 3 at 6 p.m. at the festival.

The comedy show, with elements of Mormonism in its themes, drives messages challenging not just modesty but also how religious and social conventions mercilessly leave many individuals so ambivalent, or even ashamed, and thoroughly disconnected from their bodies. The play premiered at the 2017 Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival.

For more information about United Solo, see the festival’s website.